A dramatic increase in demand for oilseeds could impact U.S. wheat production in coming years, with significantly more acres expected to be planted in soybeans destined for new and expanded crushing facilities.

Between 20 million and 25 million additional acres of soybeans will be needed to meet requirements of the renewable diesel industry, some analysts are predicting.

At the same time, global demand for wheat is also expected to rise, setting up dynamic competition for acreage in states where both crops are grown. For the U.S. wheat industry, the situation creates important questions: How much wheat acreage could potentially be lost to soybeans? Will lost acres impact the U.S.’ standing as the world’s most dependable wheat supplier? Can wheat and soybeans co-exist in a competitive environment?

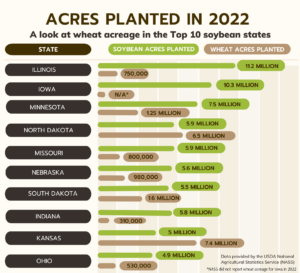

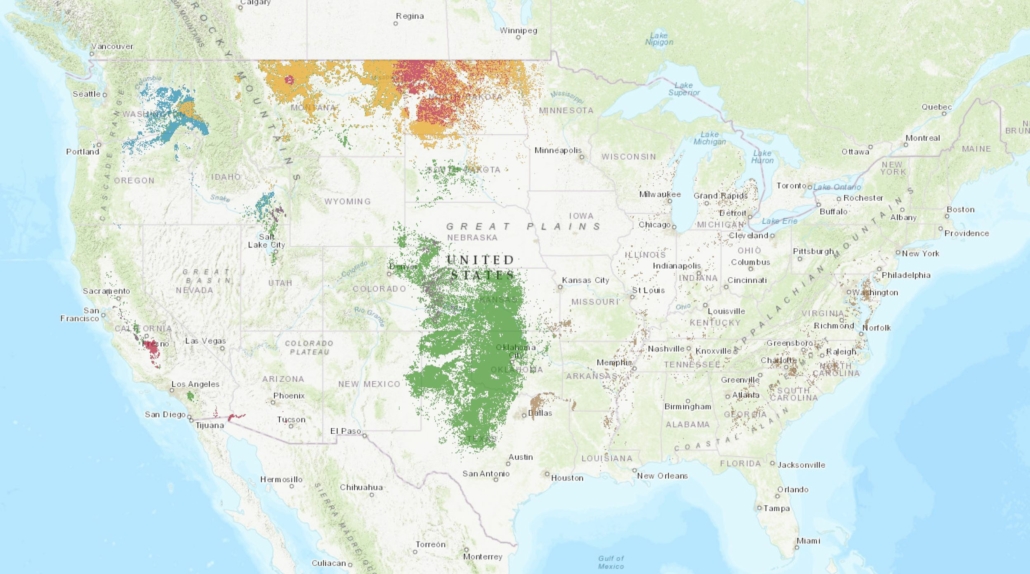

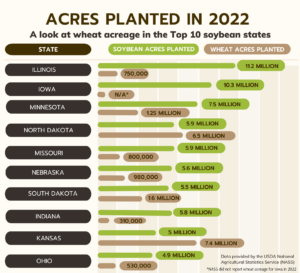

This chart shows total acreage planted in soybeans and total acreage planted in wheat in the country’s top 10 soybean states in 2022, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS).

Where possible, farmers may adapt and double-crop more wheat and soybeans to maintain supplies of both crops. It is already a common practice in top soybean states like Illinois, Indiana and Ohio, where soft red winter wheat is the dominant class. But in soybean states that produce hard red winter and hard red spring wheat – Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota, for example – allotting acreage is more complicated due to average rainfall and shorter growing seasons.

The ultimate question is if U.S. farmers will be able to meet the demand for both wheat and soybeans by doing what they have always done – figure out a way to do more with less.

Many Options, Limited Acres

Mike Krueger, a grain industry consultant with Lida Communications, put a spotlight on the emerging “competition for acreage” during last month’s U.S. Wheat Associates World Staff Conference.

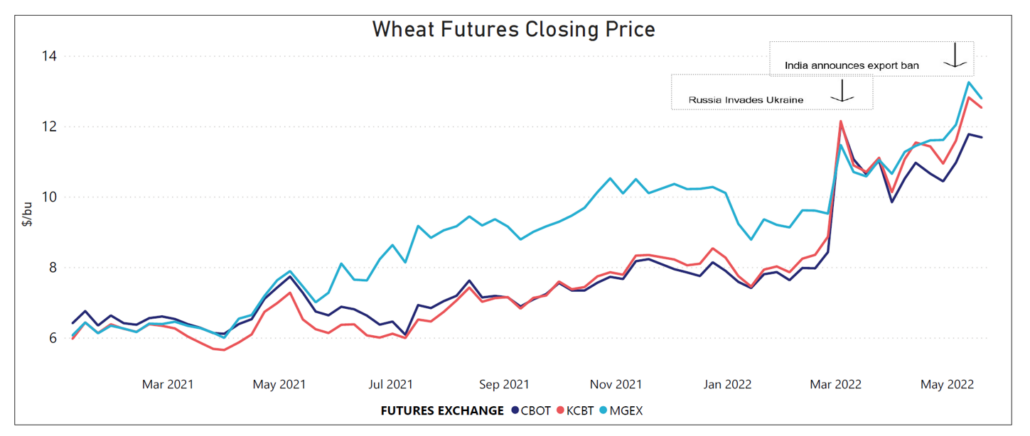

While describing volatility in global wheat and grain markets due uncertain market conditions, Krueger noted a more predictable factor that will affect markets and decisions made by U.S farmers.

“Renewable diesel is projected to increase eight-fold by 2030 and significant investments of more than $2 billion are being put into new and expanded soybean processing plants in the U.S. right now,” Krueger explained. “The U.S. soybean crush will expand by 10%, or more. We are talking vast numbers, and while sunflower and canola should be big beneficiaries of renewable diesel, soybeans are certainly going to be in even higher demand.”

A boost of 20 million acres would catapult soybean and go a long way toward meeting the projected oilseeds demand.

But at what cost?

The U.S. has consistently ranked as one of the top five wheat producing countries in the world and one of the top three wheat exporting countries. Would a major shift in acreage affect U.S. production, thus its place as a supplier?

“We must remember there’s also a global demand for wheat, as well as corn, and we have to consider ongoing drought and weather patterns, not to mention political conflicts that are impacting grain production and supplies all over the world,” Krueger said. “All of this, all the things going on that affect global trade, will put major emphasis on overall crop production in the U.S. and the entire Northern Hemisphere. To be honest, no crop can afford to give up or lose acres.”

Can Double-cropping Help?

Higher prices caused by global demand for wheat and soybeans appears to be motivating more farmers in the Midwest to consider seeding soft red winter wheat in the fall and soybeans in the same field following wheat harvest.

About 40% of producers responding to a Purdue University Ag Economy Barometer survey in June indicated they have utilized a wheat and soybean double-crop rotation in the past. About 28% of those producers planned to increase the amount of cropland devoted to this rotation by seeding more wheat this fall followed by soybean plantings on the same acres in spring 2023.

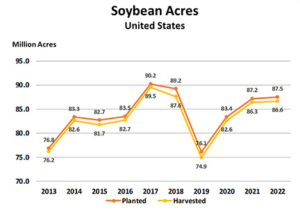

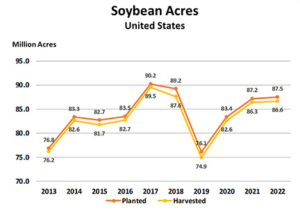

Some analysts have predicted that renewable diesel demand in coming years will require the planting of at least 20 million additional acres of soybeans. This chart from USDA shows soybean acreage and harvest over the past decade.

Ultimately, the biggest factor behind whether farmers begin growing an extra crop of wheat is what price they can get for the crop.

“The shift toward increasing soft red winter wheat acreage is likely the result of the expected profitability improvement of the wheat and double-crop soybean rotation,” James Mintert and Michael Langemeier, authors of the Purdue survey, noted.

A move by the federal government earlier this year to increase the number of counties eligible for double-cropping insurance was a move aimed at boosting U.S. production of wheat and soybeans by reducing the risk for farmers who decide to take the double-crop route.

Producers are well-aware that there are drawbacks to double-cropping wheat and soybeans.

“Compared to single-crop soybeans, double-crop soybeans have a shorter growing season due to the delay in planting until the wheat is harvested, which often result in reduced yields,” said Scott Gerlt, Chief Economist for the American Soybean Association (ASA). “Despite this drawback, double-cropping does allow increased production.”

Wheat Demand to Grow

Despite questions about acreage and production, U.S. wheat continues to be in demand by international customers because of its consistent quality and reliability.

Krueger expects the demand will continue to expand.

“A primary reason is that global wheat supplies are likely to shrink due to a renewed focus on soybeans, and to a lesser extent, corn,” Krueger said. “Another factor favoring U.S. producers involves shipping and logistics limitations that hamper competing wheat-growing countries, including Russia and Ukraine.”

Effects from a third consecutive La Nina would further pressure global supplies.

“These things will undoubtedly lead to more export demand for wheat,” Krueger said. “Can the U.S. meet the demand? That is the puzzle that’s still being put together. Farmers make decisions every single planting season. They only have so many acres to work with.”