Exploring opportunities for hard red winter (HRW), soft red winter (SRW) and durum wheat in both established and emerging markets, U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) led a team of wheat producers and industry representatives to meet with customers and learn about milling and baking processes in Mexico, Ecuador, and Colombia.

USW’s Latin America Board Team included Chet Creel of Texas, Michael Edgar of Arizona, and Keith Kennedy of Wyoming.

“We had a really good group with diverse interests that visited some very important markets to see how millers and bakers use the quality wheat produced back home – and why the quality is important to them,” said USW Director of Trade Policy Peter Laudeman, who led the team on the 10-day mission. “The goal of these Board Teams is to provide a broad canvas of a region, on-the-ground, face-to-face experiences in the mills, in the bakeries, and at the transportation facilities that support movement of U.S. wheat into the countries.”

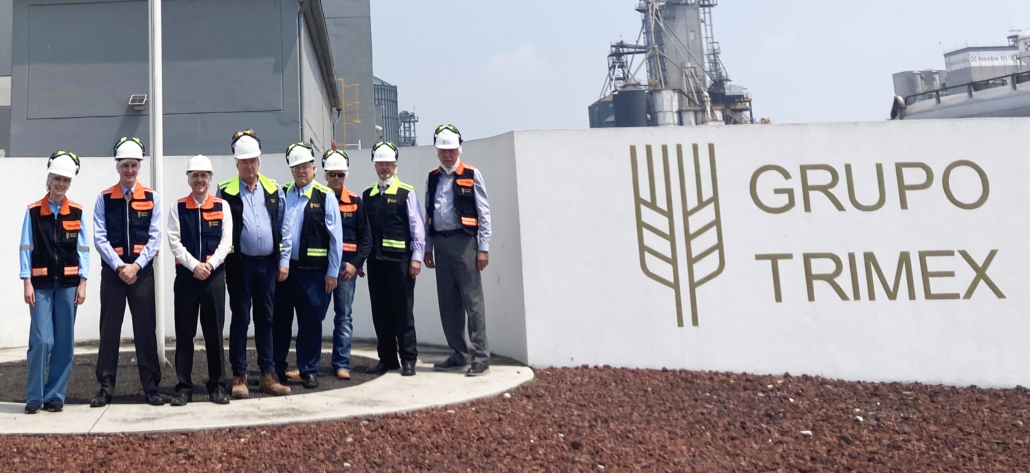

USW’s Latin America Board Team poses for a photo with USW staff and milling staff in front of a Grupo Trimex facility in Mexico following a tour and discussions about U.S. wheat.

Mexico: U.S. Wheat’s Top Customer

Stops in Mexico included Guadalajara and Mexico City. Outside of Guadalajara, the team visited the Grupo Kasto mill, shuttle train and elevator facility that receives direct rail shipments of U.S. wheat. shuttle train and elevator facility that receives direct rail shipments of U.S. wheat. From there, the team traveled to the Guadalupe Flour Mill to meet with owners of the mill. The Guadalajara portion of the trip also included a tour of the OhLaLa! baking facilities.

In Mexico City, team members visited the USW office, where they learned more about Mexico’s milling industry and efforts to promote wheat foods in the country. Visits to Grupo Trimex and Harinera Anahuac flour mills followed, helping the team explore opportunities for U.S. wheat.

“It was clear U.S. Wheat’s staff has a great relationship in Mexico and there is a lot of trust,” said Creel, Vice Chairman of the Texas Wheat Producers Board and a HRW wheat producer. “We were able to see how activities like technical servicing and educational courses have helped the Mexican milling businesses. We also saw the value of the relationships the representatives in Mexico been built and maintained over the years.”

Ecuador and Colombia: Markets With Great Potential

After Mexico, the team moved on to Ecuador, where it met up with USW representatives serving South America from an office in Santiago, Chile. In Quito, Ecuador, the team visited flour mills and a cookie factory before moving on to Cali, Colombia, for a mill visit. The next day, in Bogota, the team toured a bakery and a pasta plant that uses U.S. durum wheat.

The USW Board Team during a tour of Grupo Superior in Ecuador.

“We had some very good interactions at each stop and had some chances to discuss opportunities for U.S. wheat as a whole,” said Edgar, a USW Board Member and member of the Arizona Grain Research and Promotion Council. “For me, a durum grower, it was valuable to specifically see where my class of wheat stands and the places where it could carve out a bigger share.”

While Mexico is the top customer of U.S. wheat, both Ecuador and Colombia have great potential to increase imports.

“We were able to meet with some companies that really prefer the quality that they’ve seen in U.S. wheat and want to continue to buy,” said Kennedy, Executive Director of the Wyoming Wheat Marketing Commission. “They have definitely seen some pricing pressures, and the competition is there, but customers in both Ecuador and Colombia were very clear that the quality of the U.S. crop is second to none.”

Developing Customers

Laudeman noted that Colombia and Ecuador have a huge amount of room for per capita wheat consumption growth.

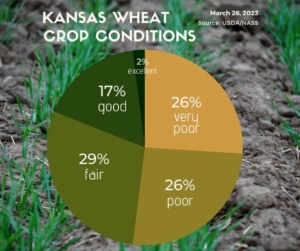

“We are looking toward the mid- to long-term opportunities to be able to sell more wheat and boost wheat foods as part of the diets in each country,” said Laudeman, who added that the team noticed interest in soft red winter (SRW) wheat in Ecuador. “As we see bigger crops and healthier crops in the future, it is going to be an easy decision for them to continue to buy U.S. wheat. Meanwhile, we will continue to work on any policy challenges that might be barriers to our market access in these countries. We will certainly keep monitoring and make sure that we can keep the policy landscape healthy. We will also continue to explore opportunities for U.S. wheat.”