By Claire Hutchins, USW Market Analyst

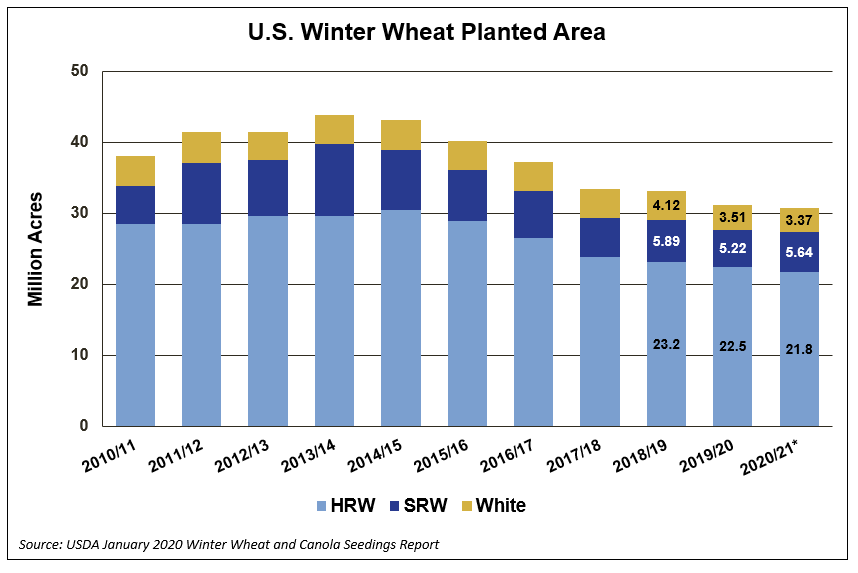

With winter wheat prices remaining at or less than the cost of production and with a very wet planting season, it is no surprise that many U.S. farmers chose to plant slightly less winter wheat for harvest in 2020. USDA’s 2020/21 Winter Wheat Seedings report, released Jan. 10, reported U.S. farmers planted 30.8 million acres (12.5 million hectares) of winter wheat, down slightly from 2019/20 and 7% less than the 5-year average of 33.2 million acres (13.4 million hectares). Decreases for HRW and white winter wheat more than offset an increase in SRW planted area. USDA noted that this is the second smallest number of winter wheat acres on record.

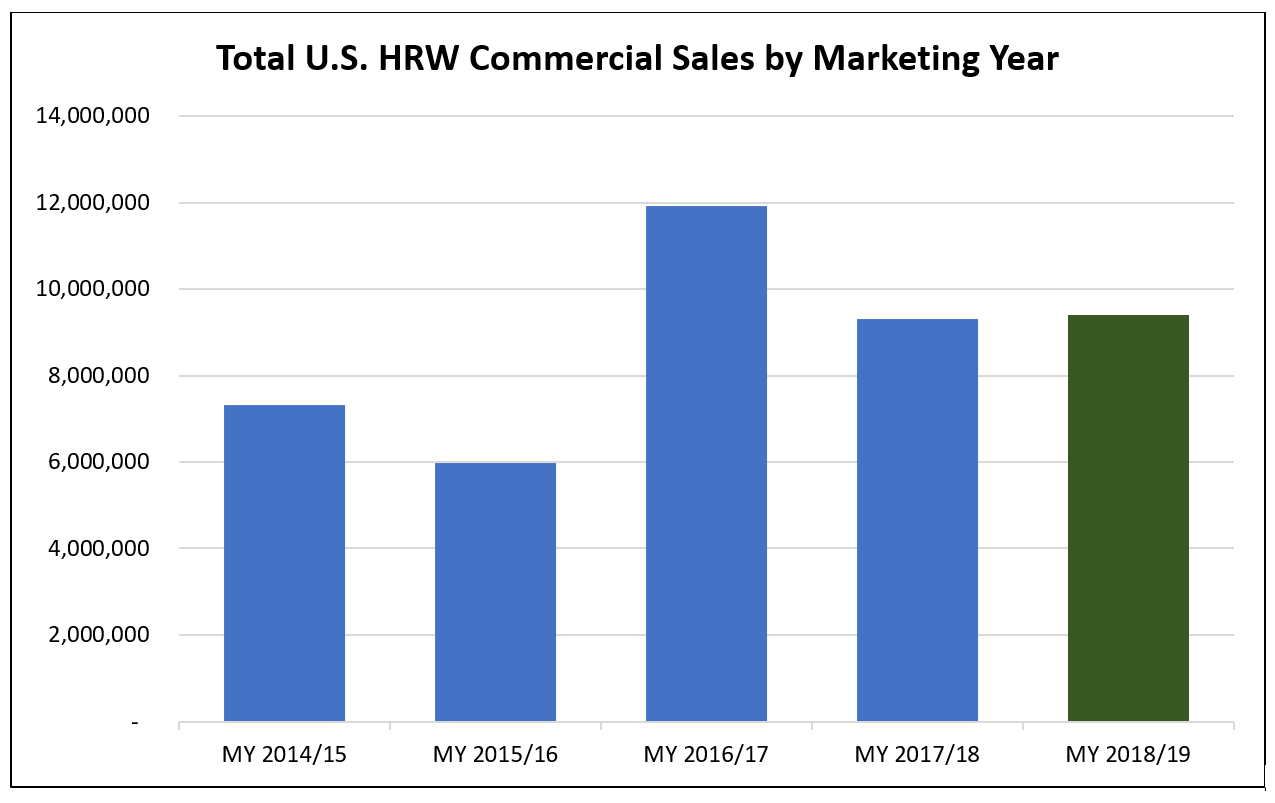

Hard red winter (HRW). USDA assessed HRW planted area at 21.8 million acres (9.35 million hectares), down 1% from 2018. Planted acreage is down year-over-year in several major HRW-producing states with the largest decreases reported in Colorado, Montana and Nebraska. Colorado planted area fell 12% year-over-year to 1.90 million acres due to extreme dryness in the southeast, depressed commodity prices and pest pressure in the northeast. Record low planted area of 900,000 acres (364,000 hectares) in Nebraska can be attributed to weaker marketing conditions and an overly wet, late soybean harvest which prevented fall HRW planting.

“This didn’t just happen overnight,” says Royce Schaneman, executive director of the Nebraska Wheat Board. “State-wide plantings have been trending down for a number of years due to poor marketing conditions.”

HRW planted area in Kansas and Oklahoma is stable year-over-year at 6.90 million acres (2.79 million hectares) and 4.20 million acres (1.7 million hectares), respectively.

Total winter wheat planted area in Texas jumped 9% year-over-year to 4.90 million acres (1.94 million hectares). About 95% of Texas winter wheat is HRW and 5% is SRW.

“Adequate soil moisture in many regions, combined with favorable marketing conditions compared to cotton, allowed producers to maximize HRW acres,” says Darby Campsey, director of communications and producer relations for the Texas Wheat Producers Board.

In South Dakota, North Dakota, Montana and Wyoming, a very wet fall also prevented more HRW seeding, although these states usually plant a relatively small percentage of total U.S. HRW.

Soft red winter (SRW). Total SRW planted area of 5.64 million acres (2.28 million hectares) increased 8% from 2018. Increases in most SRW-producing states more than offset decreases in Delaware, Illinois Indiana, Michigan, Missouri and Wisconsin.

According to Tadd Nicholson, executive director of the Ohio Corn and Wheat Growers Association, the state’s SRW planted area increased 12% over last year to 560,000 acres (227,000 hectares) due to ideal, timely planting conditions following a miserably wet spring which left many corn and soybean acres unplanted.

In Illinois, SRW planted area fell 25% from last year to 490,000 acres (198,000 hectares).

“It was one of the craziest years for weather in Illinois,” says Mike Doherty, interim executive director of the Illinois Wheat Association “It was the third wettest year on record and most of the precipitation fell in the first eight months. Farmers were beside themselves trying to manage other crops through the wet weather. Across the state, corn and soybeans were harvested 30 to 60 days late. You just can’t plant winter wheat if you can’t get the other crops out of the ground.”

There is also SRW grown in areas of Texas and Campsey reports that “strong marketing opportunities and better, dryer planting conditions for SRW compared to last year’s overly wet field conditions led to a significant increase in SRW acreage year-over-year.”

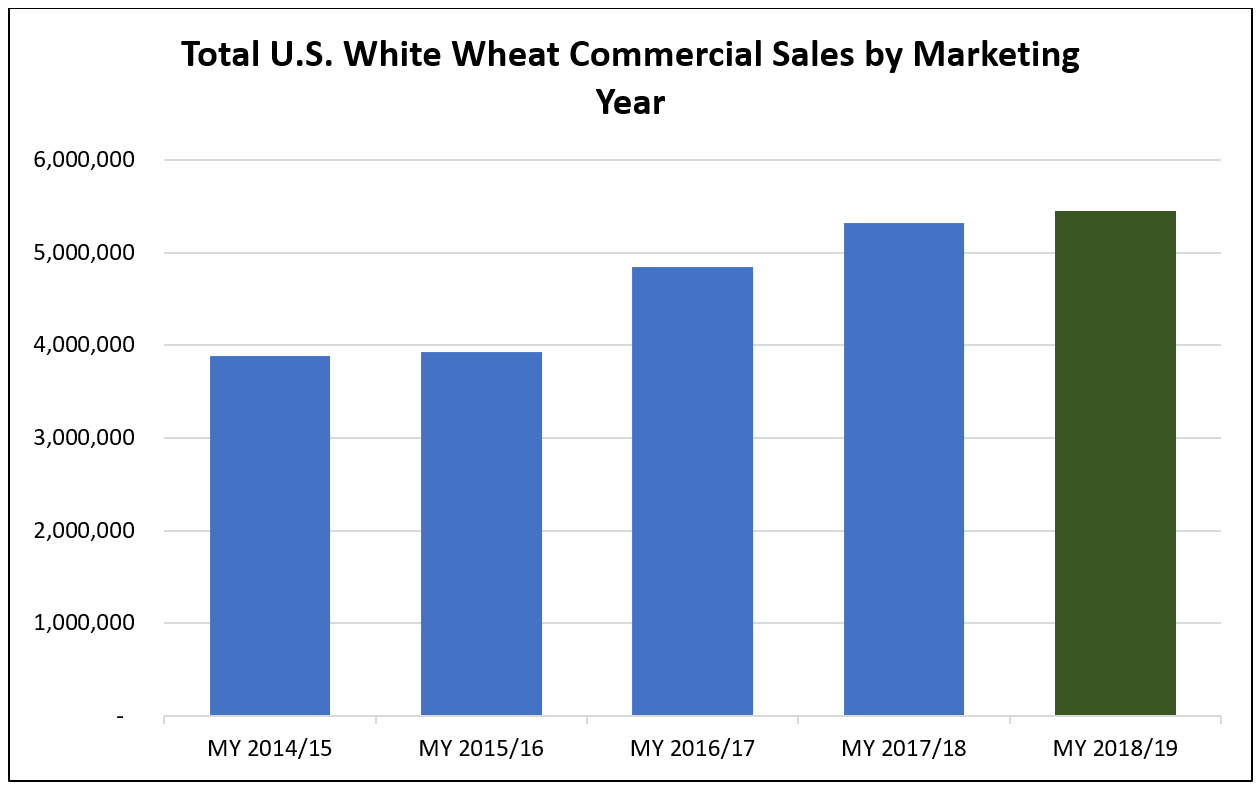

White winter wheat. White winter wheat planted area fell to an estimated 3.37 million acres (1.36 million hectares), down 4% from 2018. White winter wheat planted area in Idaho, Oregon and Washington fell below last year. Idaho farmers reported planting 720,000 acres (291,000 hectares) compared to 730,000 acres (295,000 hectares) in 2018. Planted area in Oregon fell 5% from last year to 700,000 acres (283,000 hectares). Washington planted area fell slightly less than 2018 to 1.70 million acres (688,000 hectares).

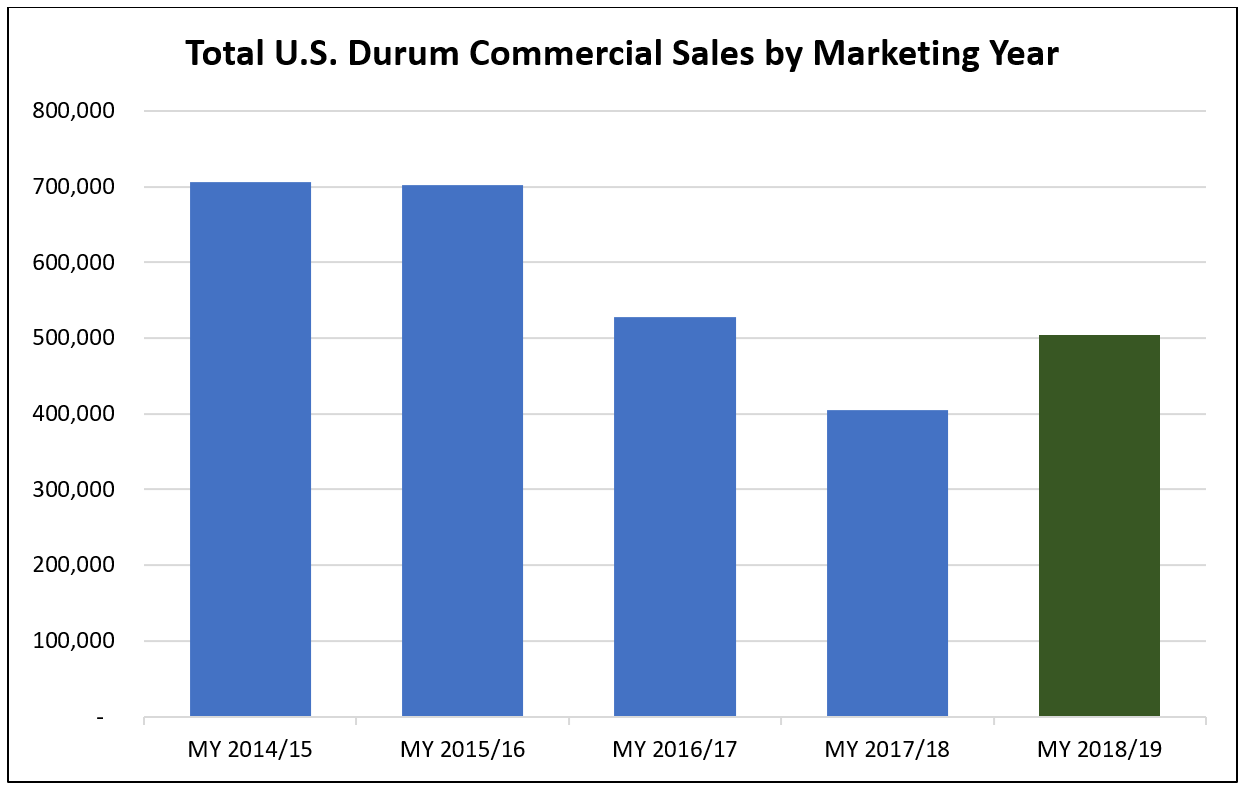

Durum. Winter durum planting in the southwestern United States is estimated at 70,000 acres (28,300 hectares), up 9% from 2018 but 41% less than 2017. Arizona and California plant Desert Durum® from December through January for harvest May through July.