Name: Andrés Saturno

Title: Technical Specialist

Office: USW South American Regional Office, Santiago

Providing Service to: Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru

Though raised in Carialinda, Venezuela, located in the mountains of Naguanagua, U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) Technical Specialist Andrés Saturno and his two brothers grew up with Italian and Spanish influences from his parents and grandmother. Bread was a big part of their table, and Saturno learned how to make many different kinds.

“Our daily consumption of wheat breads included close to twenty bollitos, which are French-style rolls, and two pan campesinos, a Spanish-style artisan bread,” Saturno said. “I also have made my favorite dish, gnocchi, from my grandmother’s recipe.”

Throughout his younger years, Saturno and his father, Andrea, a professional miller, worked on presentations related to wheat flour for his school science fairs. Saturno said their best presentation compared the properties of wheat gluten with other cereals. For this, they produced and displayed rice flour bread “that looked like a stone” and “beautiful wheat flour bread.”

Like Father, Like Son

In Saturno’s childhood, the group of mills where his father worked as the general manager and as the first Director of the Latin American School of Milling, known as ESLAMO, also made quite an impression.

“I was always fascinated to see the trains loaded with wheat entering the mill where my father worked,” Saturno said, “and with the analysis equipment in the ESLAMO milling school that USW had originally donated.”

After high school, Saturno was undecided if he wanted to be a mechanical engineer or a chef, but his father’s career influenced him to major in milling engineering. Saturno decided to attend Universidad Panamericana Del Puerto, where his father had started the milling engineering major, and he took great interest in the specific food processes and engineering behind milling.

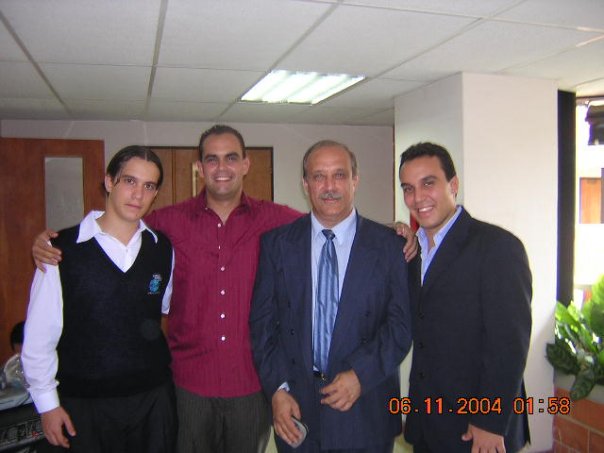

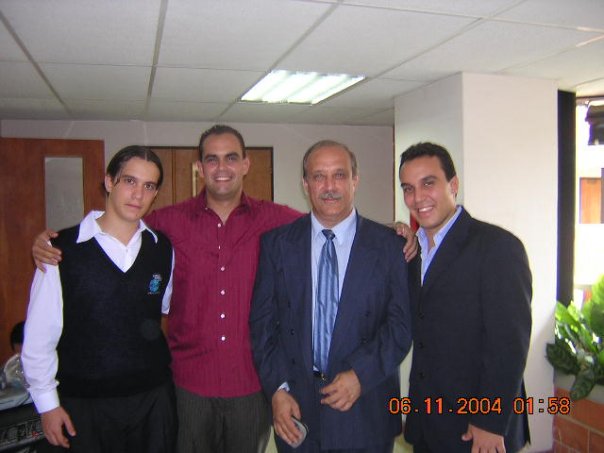

Andrés (far right) with his father, Andrea (middle right), and his brothers in 2004.

“My dad has always been an example for me as a person and as a professional,” Saturno said. “Everyone said good things about him, and that influenced me even at school.”

Building a Career

During his time at the university, he honed his skills at ESLAMO and gained more experience with wheat, flour, baking, and pasta analysis. Saturno said that his time at the university and ESLAMO gave him the theoretical and practical tools to understand and solve problems in the milling process.

Andrés and his classmates at the ESLAMO milling school.

After graduation, Saturno’s first job was at a durum mill owned by a pasta factory. Saturno learned about milling semolina, pasta production, and how to operate a mill built in the 1950s. Saturno then worked at a food consulting company installing milling equipment and accessories and various other agro-industry equipment in animal handling facilities and feed plants. While working for the food consulting company, he had the opportunity to return to his university to teach milling.

“It was the most beautiful job I had,” Saturno said. “I still have communication with my students. Nothing is more rewarding than teaching.”

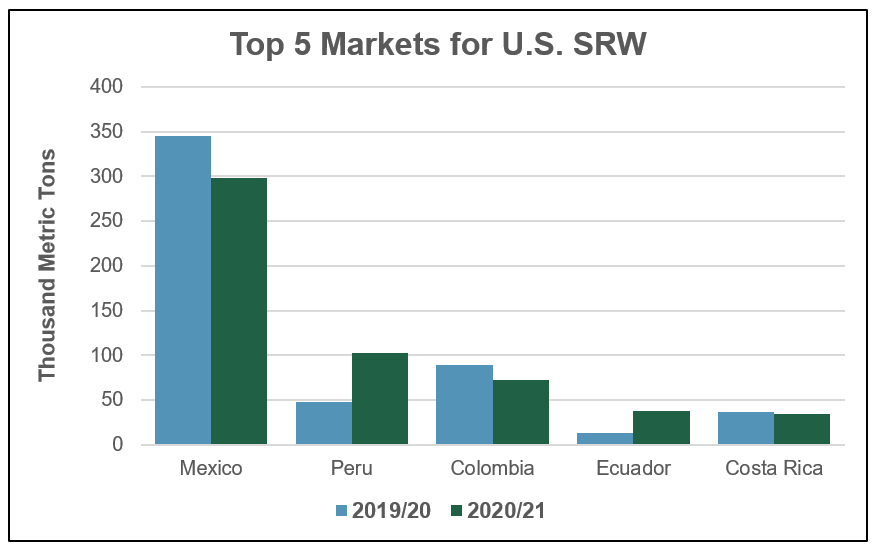

Building on his work at an older, established mill, Saturno moved to Honduras to work as the head of milling production in a brand-new flour mill. While there, Saturno learned how to grind U.S. soft red winter (SRW) wheat and produce flour for products like tortillas by blending different wheat classes.

Here, Saturno is providing in-plant technical service for a customer in Brazil.

The Right Fit

During Saturno’s time in Honduras, USW worked with its state wheat commission member organizations in the Pacific Northwest to develop and fund a new technical specialist position based in its South American regional office in Santiago, Chile. Changes in regional markets significantly influenced the need to add technical expertise in flour milling and blending. Someone with that experience and good communication skills would be needed.

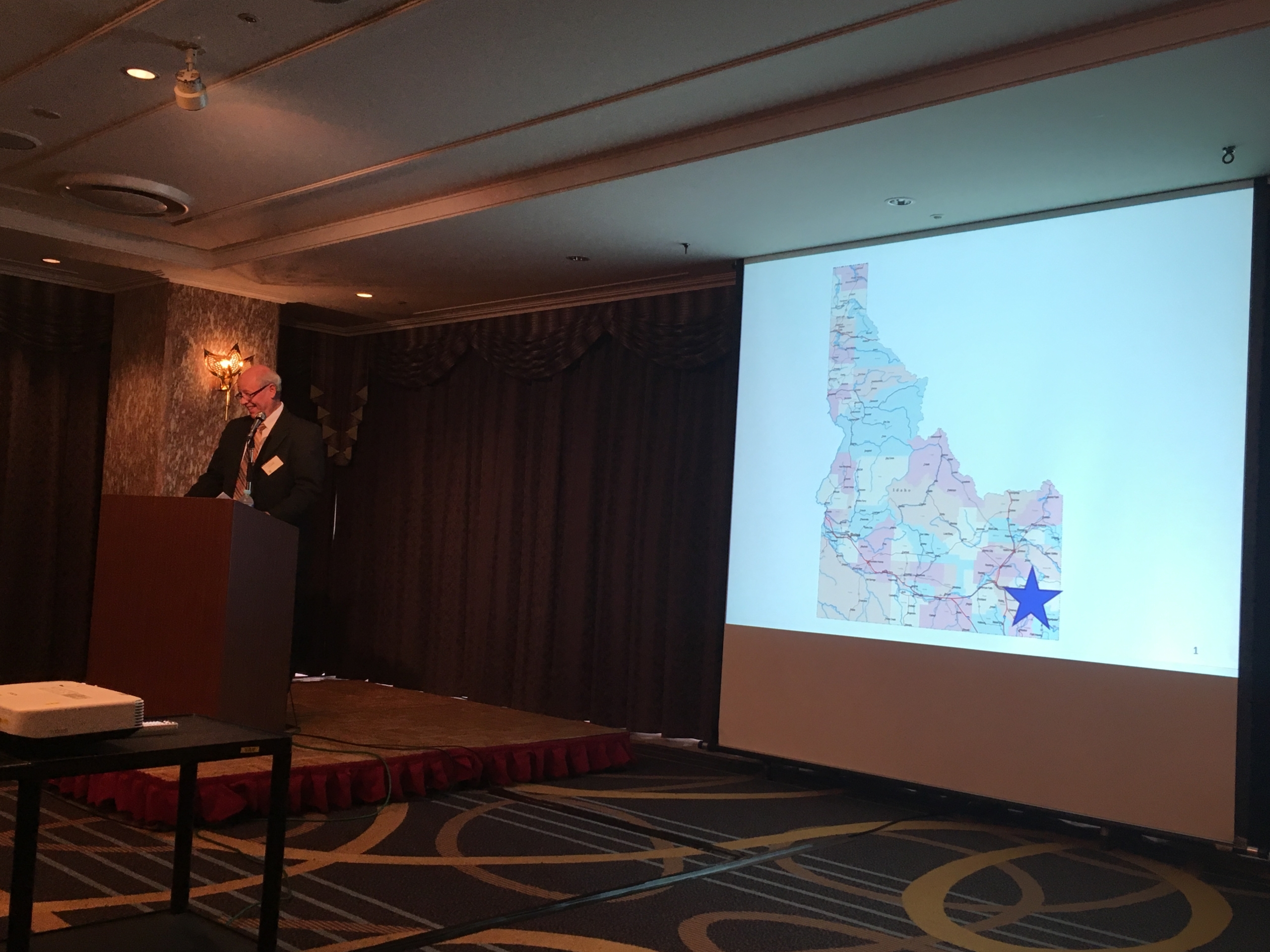

During the search in early 2018, Casey Chumrau, who at the time was serving as USW Marketing Manager in the South American region, and is now executive director for the Idaho Wheat Commission, reached out to Andrea Saturno, who had been working with USW as a milling consultant since 2013, to ask about potential candidates.

“Turns out, his son, Andrés, was looking for a new job,” Chumrau said. “Since we had been working with Andrea, I knew we would have to be extra diligent in vetting his son to avoid any bias,” Chumrau said. “From the first contact, however, Andrés was extremely professional and showed a lot of potential. We knew he had the passion and personality to do the job,” Chumrau added. “Once Mark Fowler (USW Vice President of Global Technical Services) confirmed Andrés had the technical knowledge, we offered him the job.”

“I loved the idea of working with many different mills and processes where wheat is involved,” Saturno said. “I received the call for the job with USW, and at that moment, I said, ‘I can’t lose this chance.’”

With USW/Santiago, Saturno’s role is to work closely with customers and technical staff in South America to provide training, technical advice, and ongoing support to millers. To accomplish this, Saturno creates seminars and technical classes for the South American region to build relationships while providing valuable information and skills to USW customers.

“Andrés has extensive soft skills and excellent relationships with regional customers and his team,” Claudia Gomez, USW Senior Marketing Specialist in the USW Santiago Office, said. “He also provides important technical knowledge in milling and very good speaking skills to [present] various technical information to our clients.”

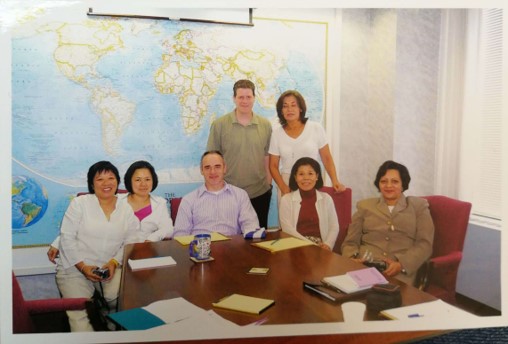

USW Brazilian Technical Trade Delegation to the United States on a visit to ADM Milling.

“Andrés’ expertise has allowed our customers to get the best out of our wheat during the cleaning, conditioning, and milling processes,” Miguel Galdós, USW Regional Director, South America, said. “Through post-sale activities, Andrés has collaborated with different mills in the region, creating confidence and loyalty with the technical staff of our customers.”

Technical Service

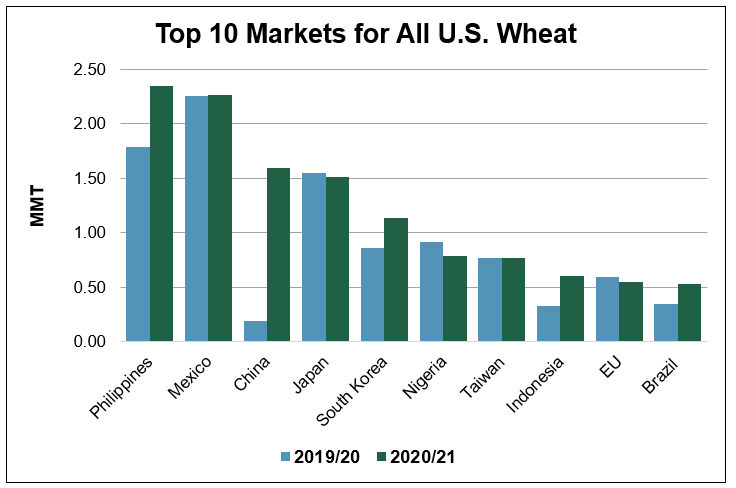

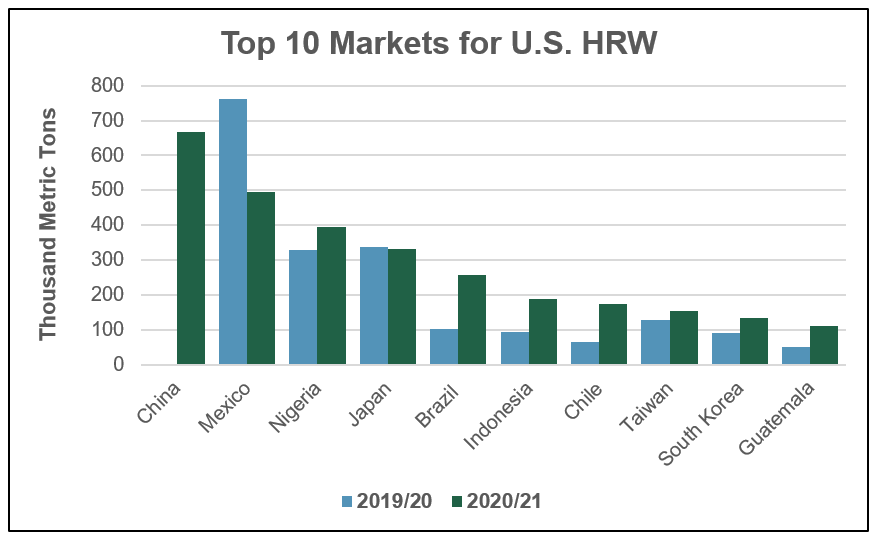

Saturno’s work helps USW Santiago provide services and training on all six U.S. wheat classes to customers in Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Colombia, and Peru. Financial support for his activities comes from state wheat commissions in Washington, Idaho, and Oregon and USDA/Foreign Agricultural Service export market development programs.

Some examples of his work include utilizing the Quality Samples Program (QSP) to introduce hard red winter (HRW) and hard red spring (HRS) wheat to a Chilean mill and soft white (SW) wheat to a mill in Colombia, leading a USW-sponsored team of Brazilian flour managers on a visit to the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service Soft Wheat Laboratory in Wooster, Ohio, and on tours of wheat research facilities at Kansas State University and Texas A&M University.

Andrés co-led a QSP and milling seminar at Molino La Estampa in Chile with his father, Andrea Saturno, and USW colleague Casey Chumrau (now Idaho Wheat Commission Executive Director). The La Estampa QSP activity encouraged the mill to import 4,500 metric tons (MT) of HRW and 1,000 MT of SRW.

“In previous years, USW was an institution that, although it had an office [in Santiago], there was no local contact to turn to in case of technical doubts,” said Maria Ines Velarde, Lab Manager, Molino La Estampa, Santiago, Chile. “The change in strategy that we have seen the last years, which included the arrival of Andrés Saturno, has meant that USW and La Estampa got closer, and that created ties and trust that allow us to have key and reliable information to make decisions at the right time.”

With Saturno as a technical specialist, USW can now give customers in the South American region more complete customer service.

Traveling with USW Santiago colleagues. (L to R) Andrés Saturno, Osvaldo Seco, Casey Chumrau and Miguel Galdos.

“This helped us widen our service area spectrum for our clients,” Saturno said. “Now we give constant technical attention to the personnel of laboratories, bakeries, milling, marketing, post-sale technicians, buyers, and owners of the mills.”

Saturno’s passion for the industry, experience in technical training, and ability to communicate with his customers has earned the respect not only of his customers but also of his colleagues.

“Andrés has contributed strong technical knowledge in the milling process, which has been a great value for all our regional customers, giving them the necessary technical support to obtain the best return from our wheat,” Galdós said.

“In addition to being a professional milling expert, Andrés is one of the best people in the world,” Chumrau said. “He truly wants each mill to be successful and doesn’t need any of the credit. He is a team player, a dedicated employee, and a great colleague. Andrés is and undoubtedly will further the mission of USW representing U.S. wheat farmers and their products.”

Andrés and his wife, Berenice, at an ALIM conference in Mexico.

Andrés and his son, Alessio Massimiliano Saturno Ramos, born on February 19, 2020.

By Dylan Davidson, USW Communications Intern

Editor’s Note: This is the ninth in a series of posts profiling U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) technical experts in flour milling and wheat foods production. USW Vice President of Global Technical Services Mark Fowler says technical support to overseas customers is an essential part of export market development for U.S. wheat. “Technical support adds differential value to the reliable supply of U.S. wheat,” Fowler says. “Our customers must constantly improve their products in an increasingly competitive environment. We can help them compete by demonstrating the advantages of using the right U.S. wheat class or blend of classes to produce the wide variety of wheat-based foods the world’s consumers demand.”

Header Photo Caption: Andrés (far right) at a USW milling seminar in Fortaleza, Brazil with fellow USW staff, Peter Lloyd (second from left) and Miguel Galdos (second to right).

Meet the other USW Technical Experts in this blog series:

Ting Liu – Opening Doors in a Naturally Winning Way

Shin Hak “David” Oh – Expertise Fermented in Korean Food Culture

Tarik Gahi – ‘For a Piece of Bread, Son’

Gerry Mendoza – Born to Teach and Share His Love for Baking

Marcelo Mitre – A Love of Food and Technology that Bakes in Value and Loyalty

Peter Lloyd – International Man of Milling

Ivan Goh – An Energetic Individual Born to the Food Industry

Adrian Redondo – Inspired to Help by Hard Work and a Hero

Wei-lin Chou – Finding Harmony in the Wheat Industry