Original article published on Oct. 12, 2017 by the American Farm Bureau Federation in collaboration with U.S. Wheat Associates.

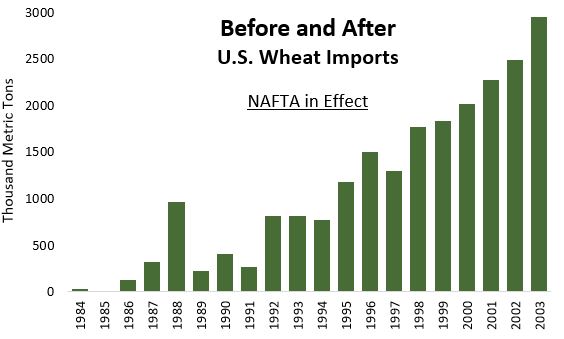

Before the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) entered into force on Jan. 1, 1994, state intervention and import tariffs held back U.S. wheat exports from the Mexican market. NAFTA ended both, and the newly opened market helped the Mexican flour milling and wheat foods industries to flourish, along with U.S. wheat imports (see chart).

USW represents the interests of U.S. wheat farmers in international markets. As it does with all U.S. wheat importing customers, USW focuses on helping Mexico’s sophisticated buyers, millers and food processors solve problems or increase their business opportunities utilizing specific U.S. wheat classes as ingredients in specific types of wheat foods. This effort, supported by wheat farmers and the partnership with the Market Access Program (MAP) and Foreign Market Development (FMD) program, has fostered a productive relationship that has endured for decades through many challenges.

Source: USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, Official USDA Estimates.

Mexico Leads All U.S. Wheat Importers

Today, Mexico is one of the largest U.S. wheat buyers in the world, importing just under 3.0 MMT on average going back many years. Mexico’s U.S. wheat imports typically only fall just short of the volume Japan imports. Not in marketing year 2016/17 (June to May), however, when Mexico’s flour millers imported more than 3.3 MMT of U.S. wheat, which is more than any other country. That volume is up 39 percent over marketing year 2015/16.

Breaking down their purchases by class, flour millers in Mexico generate strong demand for U.S. HRW wheat. The association representing Mexican flour millers says a rising number of industrial bakeries, along with traditional artisanal bakeries, account for about 70 percent of the country’s wheat consumption. That puts HRW producers in a good position to meet that demand. In 2015/16, Mexico was the leading HRW importer and buyers took advantage of favorable prices and the high quality of the 2016/17 HRW crop to import 2.0 MMT. That is 79 percent more HRW imports compared to 2015/16 and again led buyers of that class. Being closer to HRW production and having a highly functioning ability to import a large share of HRW directly via rail from the Plains states — duty free under NAFTA — is an advantage for Mexico’s buyers.

In addition, Mexico is home to Bimbo, the world’s largest baked goods company, and an increasing number of other cookie and cracker companies. The functional properties of U.S. soft red winter wheat (SRW) is well suited to the production of cookies, crackers and pastries, and serves as an excellent blending wheat. Millers supplying this growing market imported an average of 1.2 MMT of SRW between 2011/12 and 2015/16. With imports from the Gulf of more than 1.0 MMT of SRW in 2016/17, Mexico was the year’s top buyer of SRW again. USW and state wheat commissions from the PNW are also helping demonstrate how millers and bakers can reduce input costs by using U.S. SW as a blending wheat for specialty flour products.

The successful story of how U.S. wheat farmers and their customers in Mexico have worked together in a mutually beneficial way under NAFTA and, for now, U.S. wheat continues to flow to our customers in Mexico. Total exports sales to Mexico returned more than $633 million to wheat farmers across the Plains and east of the Mississippi River in 2016/17.

The data for this map is based on Mexico’s market ranking for primary class of wheat grown in that state in the 2015/16 marketing year. Most wheat states’ farmers rely on Mexico as their number one market.

Source: Small Grains Summary and Export Sales, USDA

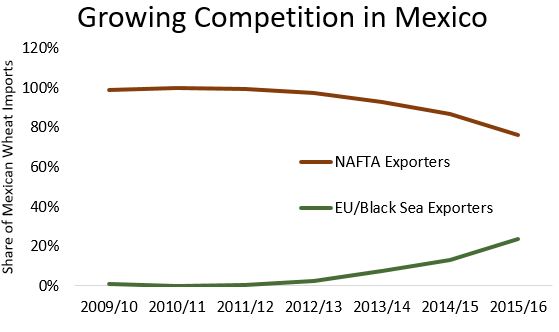

Increasing Competition

With U.S. wheat farmers facing financial hurdles, open access to the Mexican market is needed now more than ever. A prosperous Mexico is crucial for U.S. wheat farmers. But these savvy Mexican milling and baking sector customers have shown they can also adapt to other wheat supplies.

After a price shock in 2007/08, Mexico lifted its non-NAFTA wheat import tariff and wheat from other origins began to trickle in. From the first single boat carrying French wheat in 2010/11, non-NAFTA imports became a quarter of all Mexico’s wheat imports by 2015/16. The cost of U.S. wheat has a freight advantage over competitors, but if Mexico encourages purchasing from other origins or a new NAFTA agreement results in impediments to U.S. wheat imports, it has plenty of supply alternatives that are ultimately harmful to U.S. wheat growers.

Source: Global Trade Atlas

New Negotiations Can Build on NAFTA’s Success

Wheat trade with Mexico under NAFTA is already open and fair, but improvements to the agreement are possible. The three NAFTA parties agreed to some improvements as part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement that could be incorporated into a NAFTA update. TPP would have updated rules on sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures, which have created major trade problems in some markets. U.S.-initiated trade restrictions often backfire on U.S. agricultural exports, so the wheat industry supports maintaining open markets for all parties.

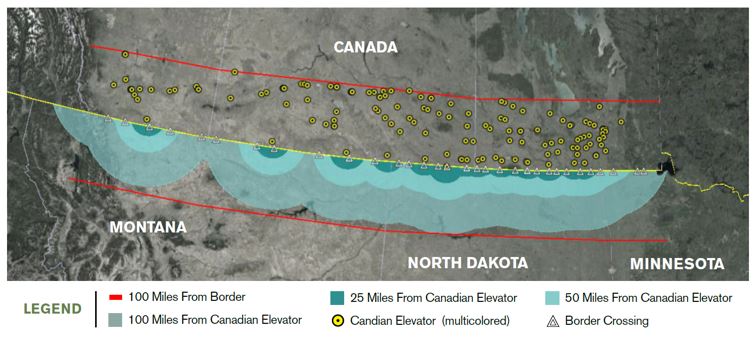

Renegotiations could also enable full reciprocity for cross-border wheat trade with Canada. Canada allows tariff-free access to wheat from the United States and certain other foreign sources. However, a Canadian law requires that imported wheat, even wheat of the highest quality, must be segregated from most Canadian wheat. It is automatically given the lowest grade established by regulation and therefore receives the lowest possible price.

By contrast, Canadian producers are free to market their wheat in the United States through normal marketing channels. When graded at a U.S. elevator, Canadian wheat is treated the same as U.S.-origin wheat and is assigned a grade based on objective quality criteria, meaning that unlike U.S. wheat going north, it retains its value when it crosses the border.

“U.S. farmers should be able to deliver their wheat to a Canadian elevator and not automatically receive the lowest grade because it was grown on our side of the border,” said Ben Conner, USW Director of Policy. “This concept is needed for U.S. wheat farmers who live near the Canadian border, is supported by the Western Canadian Wheat Growers Association, and is already Canada’s legal obligation under existing trade agreements.”

The map above illustrates U.S. land that would be most affected by an open border with Canada for wheat via truck. The blue rings represent land south of the border that is within 25, 50 and 100 miles away from a Canadian elevator.

Do No Harm, Please

The U.S. wheat industry welcomes the opportunity for improving the framework for cross border wheat trade between the United States, Canada and Mexico, but would strongly oppose changes that might limit the current NAFTA’s benefits for wheat farmers and their customers, particularly in the Mexican food processing industries.

“I cannot emphasize enough how important our Mexican customers are to U.S. wheat farmers,” said Jason Scott, a wheat farmer from Easton, Md., and USW Past Chairman. “There is nothing wrong with modernizing a 23-year-old agreement, but that must be done in a way that benefits the food and agriculture sectors in both countries.”