By Shelbi Knisley, USW Director of Trade Policy

The COVID-19 pandemic is threatening to push an estimated 71 to 140 million people into extreme poverty according to studies by the United Nations and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). According to the IFPRI study, “a global health crisis could thus cause a major food crisis—unless steps are taken to provide unprecedented economic emergency relief.”

U.S. wheat farmers, U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) and the National Association of Wheat Growers (NAWG) have been partners in U.S. international food assistance programs for more than 50 years. They have encouraged strategies that include the full range of options to help countries attain lasting and sustainable food security. And U.S. support of food aid programs is more important now than ever.

The pandemic threatens the people who were already severely suffering from food insecurity, especially in areas of Africa and Asia. The USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) and United States Agency for International Development (USAID) food assistance programs, sustained by U.S. commodities, are ideally prepared to help these countries in extreme need.

There are three major U.S. food aid programs. USDA administers Food for Progress and McGovern-Dole Food for Education. Food for Progress supports countries in modernizing and strengthening their agricultural industry, while McGovern-Dole supports education and food security in low income and food insecure countries. USAID’s program Food for Peace is under Title II of the Food for Peace Act, which is an emergency feeding program.

Wheat is an important component of these programs. Some years the U.S. government donates enough wheat for feeding programs and monetization to count as a top-ten U.S. wheat export market. In marking year 2019/20, for example, U.S. wheat accounted for more than 900,000 metric tons (MT) of food aid donations through USDA and USAID programs, and represented almost four percent of U.S. commercial shipments. This is a source of pride to U.S. wheat farmers.

Much of this wheat was distributed under USAID’s Food for Peace program. The largest recipients of this program, over about the last 5 years, are Ethiopia and Yemen, which has received soft white wheat as the country continues to suffer under civil war.

In August 2018, the World Food Programme (WFP) and USAID hosted an event in Portland, Ore., to bring attention to the need for food in Yemen and the ongoing U.S. efforts to provide aid. The media event was held across the Willamette River from an export elevator where government-purchased SW wheat was being loaded into an bulk container ship bound for Yemen.

With food insecurity on the rise, driven by the current pandemic, it is even more important to ensure food is being provided to those in need. Not only is food aid important in helping to feed a growing global population but also aids in advancing developing countries’ agricultural industries through the support of U.S. commodities.

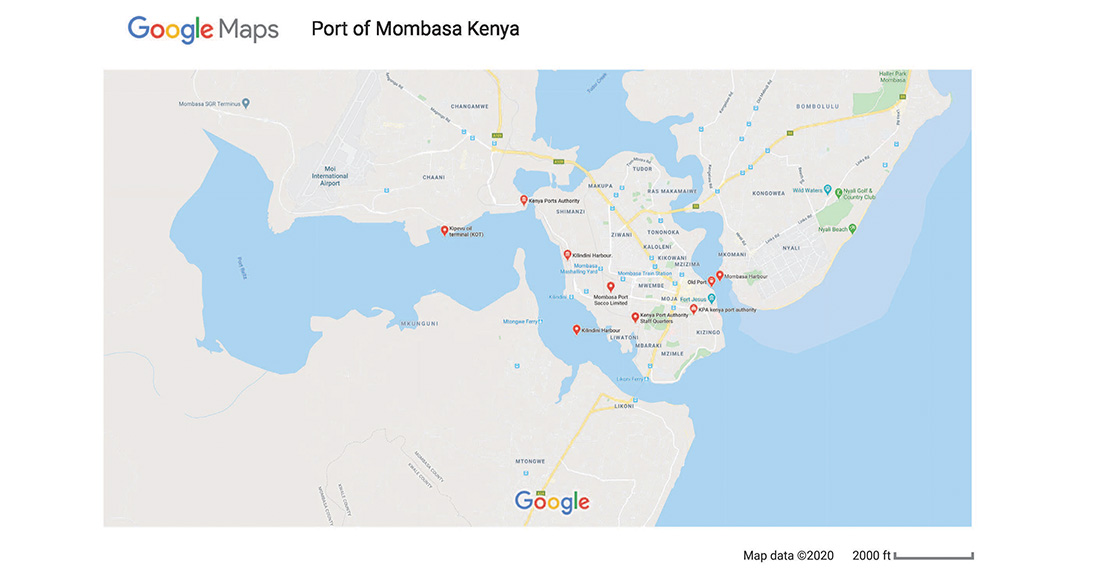

USW believes it is important to engage our farmers and staff as much as possible in these important food aid programs. In the fall of 2019 USW organized a food aid trip to Tanzania and Kenya which included members and staff from the rice, sorghum, and wheat industries. Trips such as this allow for U.S. growers to see first-hand how their commodities are contributing to these programs and to share their experiences and the good work the United States is doing for others in need.

Farmers representing USW, NAWG, U.S. Grains Council (USGC), and USA Rice spent 14 days in Kenya and Tanzania in November 2019 to see how donation programs help improve lives. The trip was funded by USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service export market development programs.

The U.S. agricultural industry, including the wheat farmers USW represents, stand ready to continue providing food and economic opportunity through monetization to the world’s most vulnerable during these uncertain