In this article, originally published during U.S. Wheat Associates’ 40th anniversary in 2020, Wheat Letter describes the highly successful public-private partnership supporting U.S. wheat export market development that has endured since the 1950s.

“The proper role of government…is that of partner with the farmer – never his master. By every possible means we must develop and promote that partnership – to the end that agriculture may continue to be a sound, enduring foundation for our economy and that farm living may be a profitable and satisfying experience.” – President Dwight D. Eisenhower, from a message to Congress on agriculture, Jan. 9, 1956.

In 2020, Wheat Letter offered historical perspective on how changes in federal programs, global market factors and relationships drew Western Wheat Associates and Great Plains Wheat Market Development Association ever closer together and led to the establishment of U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) as a single export market development organization to serve all U.S. wheat farmers.

A formal agreement between the Nebraska Wheat Commission and USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) to co-fund and implement export market development activities in 1958 marked the beginning of an enduring partnership between farmers, state wheat commissions, FAS and USW after the merger in 1980.

“I consider this to be one of the most successful partnerships between a U.S. government agency and private industry,” said USW President Vince Peterson. “Each partner brings unique core capabilities that support the export development mission. Our activities are jointly planned, funded and evaluated. We all share the risks, responsibilities and results.”

It Starts with the Farmer

State wheat commissions exist under state law generally to conduct promotion and market development through research, education and information. Commissions are funded by assessments paid by the farmer either by bushel or by a portion of the price at the time of sale. This is called a “checkoff” and though it is voluntary, a strong majority of farmers contribute their assessment. Farmer commissioners, either elected by their peers or appointed by their state’s governor, direct how the checkoff funds are to be used, such as for domestic promotion, public crop production research and variety development and export market development.

In 2017, Ralph Bean, who was then Agricultural Counselor, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, U.S. Embassy Manila (far right), met with farmers from South Dakota, North Dakota and Montana during their USW Board Team visit to South Asia . The farmers were guests of honor at the 9th International Exhibition on Bakery, Confectionary and Foodservice Equipment and Supplies, known as “Bakery Fair 2017,” hosted by the Filipino-Chinese Bakery Association Inc.

By agreeing to contribute a portion of checkoff funds to USW for export market development, state wheat commissions choose to become members of USW. The annual USW membership assessment is about $0.004 per bushel, multiplied by the average production in the state over the past five years. Currently 17 state wheat commissions are USW members.

The contributions from state wheat commissions, including special project funds as well as the personal time and talent invested by farmers and U.S. wheat supply chain participants, supports the USW mission to develop, maintain and expand international markets to enhance wheat’s profitability for U.S. wheat producers and its value for their customers. In addition, state commission contributions qualify USW to apply for federal export market development funds administered by FAS.

Linking U.S. Agriculture to the World

USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service has primary responsibility for overseas programs including market development, international trade agreements and negotiations, and the collection of statistics and market information. It also administers the USDA’s export credit guarantee and food aid programs and helps increase income and food availability in developing nations by mobilizing expertise for agriculturally led economic growth. The FAS mission is to link U.S. agriculture to the world to enhance export opportunities and global food security.

Jim Higgiston (left), who was then USDA/FAS Minister Counselor for Agricultural Affairs, met with Regional Director Chad Weigand (right) and farmer members of a USW Board Team in September 2018 in the capital city of Pretoria, South Africa. The FAS team in Pretoria included Kyle Bonsu, Agricultural Attache, Laura Geller, Senior Agricultural Attache, and Dirk Esterhuizen, Senior Agricultural Specialist.

FAS export market development programs available to USW as a cooperating organization include the Market Access Program (MAP), the Foreign Market Development (FMD) program, the Agricultural Trade Promotion program and the Quality Samples Program. USW is required to conduct an extensive, annual strategic planning process that carefully examines every market, identifying opportunities for export growth and recognizing trends or policies that could threaten existing or prospective markets. FAS reviews this annual plan, the Unified Export Strategy (UES), results from previous years and private commitments to determine how USW will invest program funds. In 2022/23, federal funding provided $2.20 for every $1.00 contributed by farmers through their state wheat commissions.

“It is important that [overseas] buyers and government officials develop direct personal relationships not only with us at USDA but also directly with American farmers and ranchers,” said former USDA Under Secretary for Trade and Foreign Agricultural Affairs Ted McKinney in testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry in June 2019.

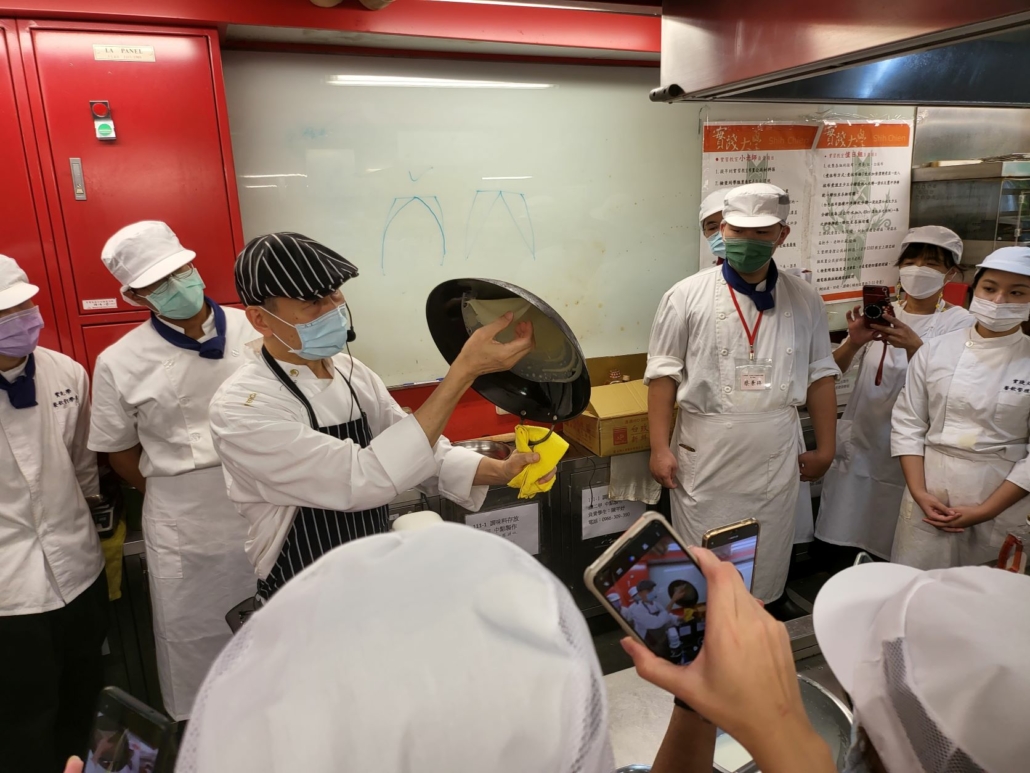

In 2017, Jeffery Albanese (pictured back row with hat), who was then Agricultural Attaché, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, U.S. Embassy Manila, joined aUSW Board Team, with farmers from South Dakota, North Dakota and Montana, and USW staff, for a tour of San Miguel Mill, Inc. in the Philippines.

USDA in general and FAS specifically foster such relationships by acting as strategic partners with USW through the extensive FAS network of foreign service officers serving in 98 offices around the world and its civil service support in the United States. The foreign service officers provide vital liaison with government officials and are active in market development work. The civil service likewise plays a critical role in everything from supporting the foreign service, managing the relationships with organizations like USW, providing market information, analyzing trade policy barriers, and much more.

FAS programs make it possible for wheat farmers to have representatives from USW who work directly with overseas wheat buyers, flour millers and wheat food processors and translate customer needs directly back to the state wheat organizations, who are in turn helping direct research for wheat crop development in their states. This leads to improved varieties and helps farmers manage their crops with the end user in mind, who would otherwise be thousands of miles and multiple steps apart in the supply chain.

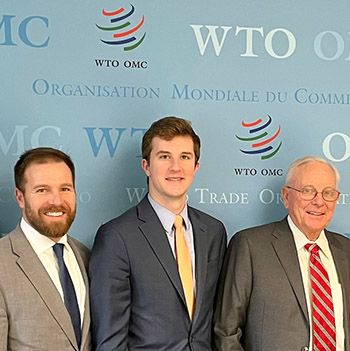

A team of U.S. wheat farmers from Kansas, Oklahoma and Arizona bound for trade visits to customers in Nigeria and South Africa met in September 2016 with then USDA Under Secretary for Trade and Foreign Agricultural Affairs Ted McKinney (center) and other FAS staff in Washington, D.C.