On Jan. 30, 2024, Casey Chumrau, CEO of the Washington Grain Commission, offered compelling testimony supporting the crucial infrastructure of dams and locks on the Columbia Snake River System (CSRS) at a U.S. House Energy, Climate, and Grid Security Subcommittee hearing. U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) and the National Association of Wheat Growers (NAWG) sent separate letters with their observations of the essential nature of the CSRS for U.S. wheat export competitiveness.

Following are excerpts from Chumrau’s testimony.

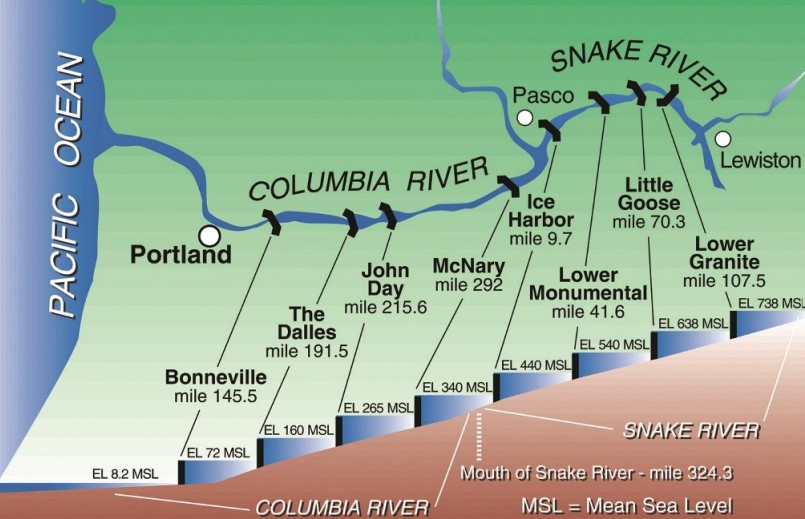

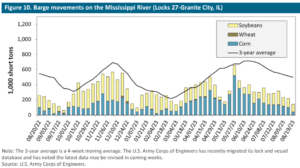

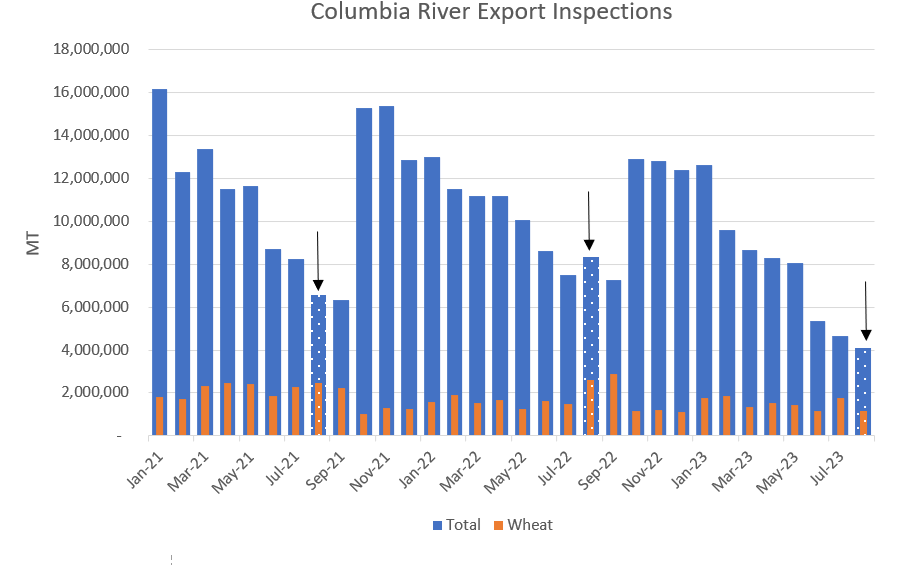

Grain growers in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) rely on the Columbia Snake River System, and the Lower Snake River Dams (LSRD) in particular, for their livelihoods. More than 55 percent of all U.S. wheat exports move through the PNW by barge or rail. Specifically, 10 percent of wheat that is exported from the United States passes through the four locks and dams along the Lower Snake River. This is especially important for our state because Washington is the fourth largest wheat exporter in the nation, exporting 90% of the wheat produced in the state. Across the agriculture industry, the Columbia Snake River System is the second largest gateway for soybean and corn exports coming from as far as the Midwest. The river system also serves as an important channel to bring crop inputs, like potash, to farmers in the region who need fertilizer to produce the safe and affordable food supply that is found on every American’s table.

Casey Chumrau, CEO, Washington Grain Commission, giving testimony on Columbia Snake River System Jan. 30, 2024, to a U.S. House Energy, Climate, and Grid Security Subcommittee hearing.

Economic Impact

Washington’s agriculture industry, and its ability to produce and export products globally, are critical to the state and region’s economy. The total value of wheat exported through the PNW is nearly $4 billion per year.

For Washington, the state is among the top 20 states for agricultural exports in the nation, with over $8 billion in Washington-grown or processed food and agriculture exports in 2022. A significant volume of food and agriculture products from other states including soybeans, wheat, and corn are exported through Washington state ports each year. Once these pass-through exports are combined with Washington-grown or processed exports, the total value reaches over $23 billion.

The Washington wheat industry alone contributed over $3.1 billion to the state’s economy in 2022, with a heightened impact in rural areas. In the same year, total direct employment associated with Washington wheat production amounted to 3,672 jobs in 2022. Indirect and induced employment also grew and supported another 11,676 jobs.

The impact that Washington farmers have on their local and regional economy is similar in communities across the country. In addition to direct sales of farm goods and commodities, farmers contribute to the economy and support other rural businesses through purchases of farm business inputs – everything from seed and fertilizer to business services. Additionally, the personal purchases of both farmers and their employees help to stimulate local economies and keep small businesses ruining.

Locks and dams on the Lower Snake River and the Columbia River provide essential infrastructure for moving U.S.-grown wheat to high-value markets around the world. We cannot overstate the positive value they create for U.S. farms, [the] economy of the Pacific Northwest and far beyond. – From USW letter to House subcommittee hearing on the Columbia Snake River System

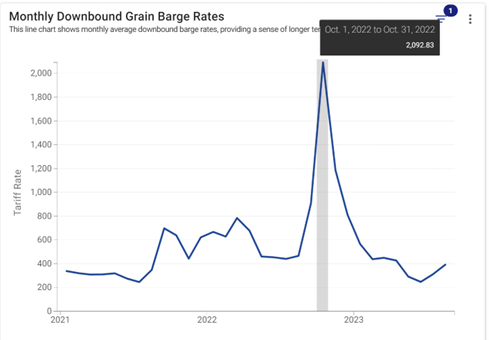

Supply Chain and Transportation

Over the last seventy years, growers and their federal government partners at the U.S. Department of Agriculture have invested billions of dollars and countless hours to build strong relationships with our trading partners. The U.S. wheat industry differentiates itself by providing high-quality wheat and reliable delivery. The United States is a reliable trading partner in large part because of our world class, multi-modal infrastructure, which allow us to safely and efficiently ship products around the world. Any disruption to that system would hurt our ability to consistently provide abundant, high-value food products and remain competitive with other agricultural exporters in the world and weaken the competitiveness of U.S. producers in global markets.

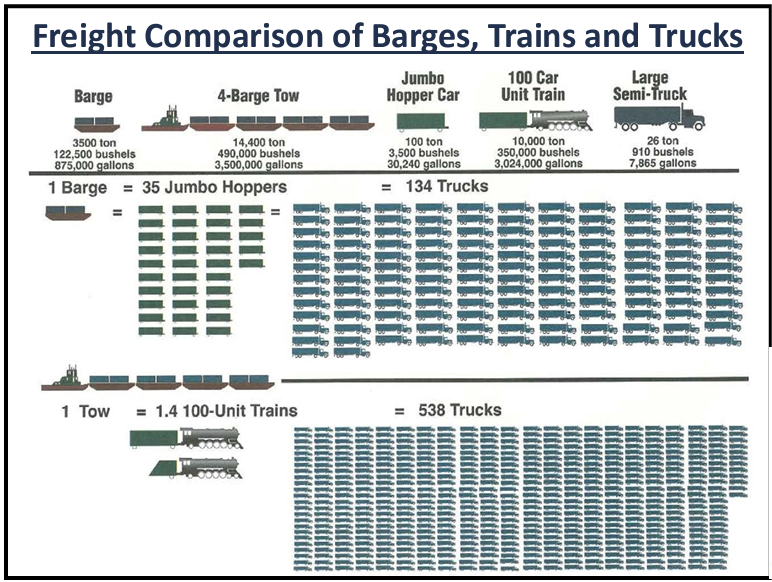

Grain growers in PNW states are at the tip of the spear of those who would feel the disruption of having to divert export goods to trucking and rail because there is insufficient alternative transportation infrastructure to replace the barge shipments of grain along the Columbia Snake River System to export markets. For example, one loaded covered hopper barge carries over 58,000 bushels of wheat. It would take 113,187 semi-trailers each year carrying 910 bushels of wheat to replace the 103 million bushels shipped on the Snake River via barge annually. That is 310 more trucks each day, making round trips to the Tri-Cities, 365 days per year. To that end, barging is the most fuel-efficient mode of transportation when compared to railroads and trucking. Each barge that must be replaced by a truck means more pollution, more traffic, increased costs and increased wear and tear on our roads – and that’s if we could even hire the drivers needed to drive these trucks in the increasingly tight labor market for drivers.

Path Forward

We strongly believe that dams and salmon can and do co-exist. With a myriad of challenges facing the salmon population, we are committed to building upon current investments and technological advancements. Currently, the Lower Snake River Dams have world-class fish passage and juvenile survival rates upwards of 95 percent. We believe any work moving forward should build off the fish passages, instead of eliminating them. We also support investments made at the federal and state level for culvert removal, fish habitat restoration, toxin reduction, and predator abatement.

Conclusion

The opportunities to ensure salmon populations continue to grow do not have to come at the cost of destroying the integrity of the Columbia Snake River System and the livelihood of farmers. The importance of the river system for the agriculture industry, and particularly for grain growers across Washington, cannot be overstated. I look forward to discussing the importance of the four Lower Snake River Dams with you today. Thank you.

To read more about this issue, see these previous “Wheat Letter” posts:

“Exports Depend on Snake River Dams“

“USW Expresses Support for Maintaining Lower Snake River Dams“