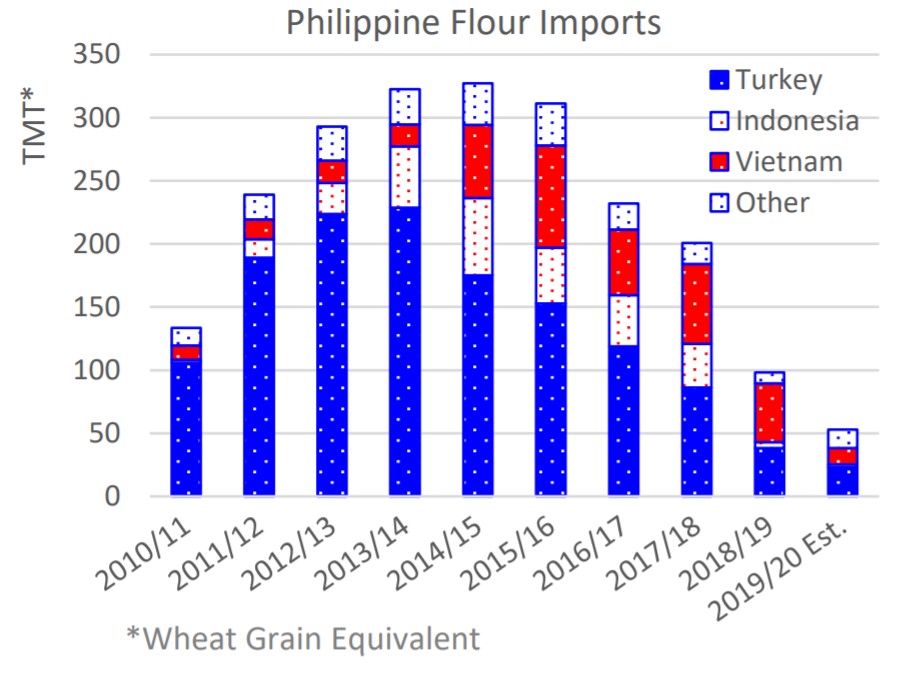

It is a country that imports about 800,000 metric tons of wheat each year, a mere 90 miles from the United States. Yet the Cuban wheat market has long been a source of optimism and frustration for U.S. wheat farmers. With the change in administrations, there is hope for re-engagement with Cuba, but ultimately the 60-year-old embargo and associated policies still stand as a solid barrier to beneficial trade.

General public opinion polls on Cuba policy consistently show most Americans favor more engagement, the last decade has seen a roller coaster of changes in U.S. policy. Under the Obama-Biden Administration, there were efforts to establish a new relationship and relax tensions. This included a new interpretation of “cash in advance” rules that apply to payment for any agricultural commodities, bilateral exchanges by technical staff in regulatory agencies and the reopening of the U.S. embassy in Havana. However, none of those changes resulted in actual wheat purchases. Then the Trump Administration further restricted trade by limiting any business conducted between American companies and state-owned companies (such as flour mills) in Cuba.

“Wheat is an important food grain that should be above politics, but the embargo will likely have to end before wheat farmers can help … feed the Cuban people.”

With Biden’s return to the White House, Cuba watchers are anxiously awaiting the next curve in the roller coaster ride and are optimistic the administration will return to the Obama-Biden policy of re-engagement. However, any realistic effort to expand ag trade with Cuba needs to focus on the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue by working to secure meaningful change within the halls of Congress and addressing the bipartisan opposition to trade with Cuba.

Just such a Congressional effort was launched last week by U.S. Senators John Boozman of Arkansas and Michael Bennet of Colorado with the introduction of the Agricultural Export Expansion Act. That bill would allow private financing of agricultural commodities by U.S. companies – a small first step toward normalizing the trading relationship, but an important one to put U.S. companies on a near level playing field when working with Cuban buyers. Several U.S. agricultural organizations including U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) and the National Association of Wheat Growers (NAWG) signed a letter of support for the effort as ad hoc members of the United States Agricultural Coalition for Cuba.

More Legislation

The Ag Export Expansion bill is not the only pro-normalization effort within Congress. U.S. Senators Jerry Moran of Kansas, Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and Patrick Leahy of Vermont, all long-time Cuba trade advocates, earlier this year introduced the Freedom to Export to Cuba Act, which would lift substantial portions of the embargo, including restrictions prohibiting transactions between U.S. and Cuban firms.

Farmers are right to be interested in opening the Cuban wheat market. Cuba produces no wheat domestically and would be a substantial U.S. market if government barriers were to be lifted. But for any of that optimism to come to fruition, it is going to take a literal act of Congress.

“Wheat is an important food grain that should be above politics,” said former USW President Alan Tracy in 2017, “but the embargo will likely have to end before wheat farmers can help meet the increasing demand for agricultural products to help feed the Cuban people.”

By Dalton Henry, USW Vice President of Policy