Late spring is a notoriously busy time on U.S. farms. This may partly explain why last month’s World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial meetings in Geneva largely came and went without much notice from U.S. farmers or farm media. Or maybe U.S. farmers have tuned out the inner machinations of a 25-year-old organization that has been promising a new agricultural agreement for more than two-thirds of its existence. Whatever the reason, the actions, both those taken and not taken, will impact U.S. wheat farmers.

The actions taken of note at the WTO Ministerial include a new declaration on sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS)* regulations and a commitment by countries to exempt humanitarian purchases by the World Food Programme from export restrictions. The latter is of little consequence to U.S. producers as U.S. laws around export restrictions are pretty tight, part of what has made the United States the most reliable wheat supplier in the world. The SPS front, though, holds more promise.

Fastest Growing Trade Barriers

Non-tariff barriers to trade (which include SPS regs) represent what we on the U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) policy team have called “the fastest-growing segment of trade barrier impacting wheat trade.” We have worked on more non-tariff barriers than traditional tariff barriers in the last calendar year. Non-tariff barriers include rules such as maximum residue limits (MRL) on pesticides and limits on weed seed species or insects. Many SPS regulations are critically important to protecting plant and human health, but, in recent years, many countries have found they are a convenient way to protect domestic producers or otherwise frustrate international trade. That the SPS rules received a major update for the first time in their existence at the WTO Ministerial and that the notoriously protectionist European Union joined in supporting them notes just how important they have become to facilitating trade.

Attempts at Weakening WTO Rules

It may seem odd to celebrate actions not taken, almost as though no progress represents a successful outcome. However, that has increasingly been the case for U.S. agriculture at WTO Ministerial meetings in the last decade.

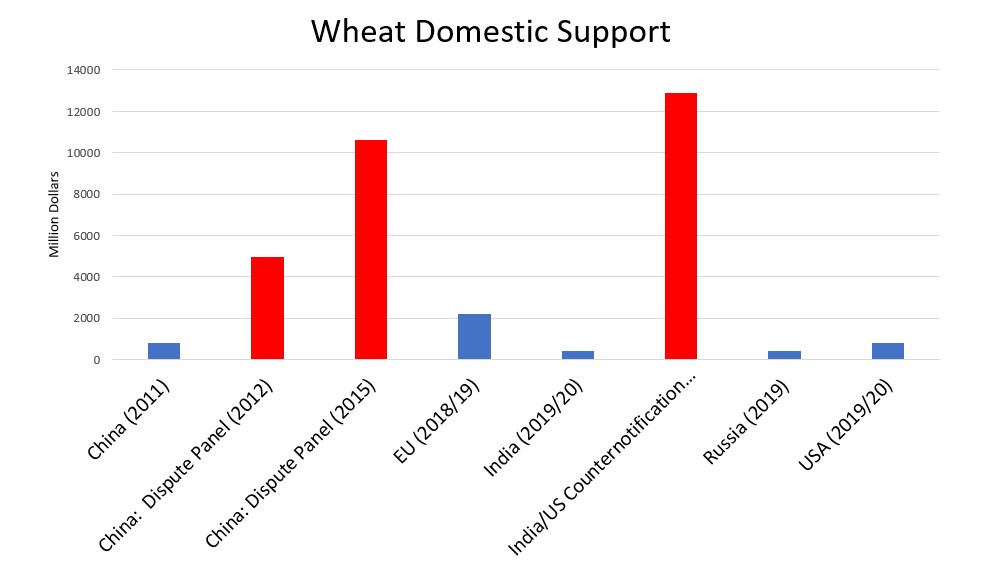

With all hopes of securing meaningful new market access for agriculture essentially dashed since 2008, several developing countries have tried to weaken existing rules. India has been notorious for this, insisting that its public stockholding programs be exempt from subsidy limits – despite exporting substantial wheat and rice stocks from those so-named food security programs. India secured a limited exception to those subsidy rules during the Bali ministerial in 2013. Developing countries also substantially, though temporarily, weakened rules on export subsidies – widely recognized as the most trade distorting form of domestic support during the Nairobi ministerial in 2015.

With those two events as background, an informal coalition of U.S. agricultural groups – “Aggies for WTO Reform” – attended the WTO Ministerial, received briefings from the U.S. government and WTO representatives, and advocated with other country delegations to hold firm in the original rules of the WTO.

Trade Rules for the Greater Good

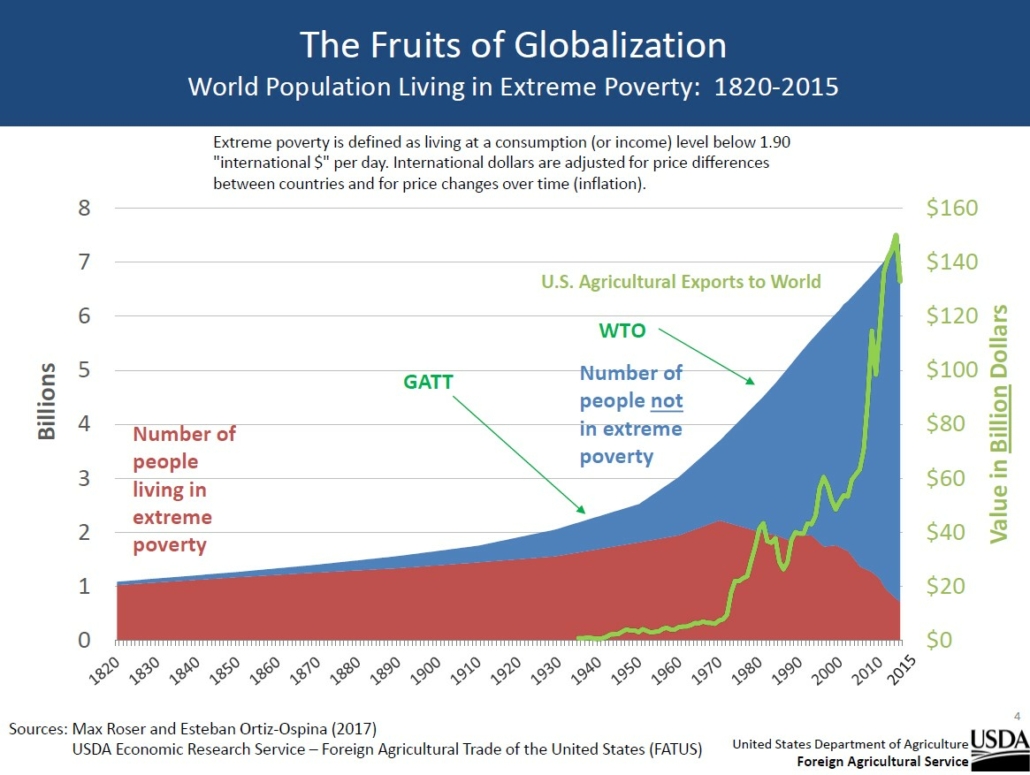

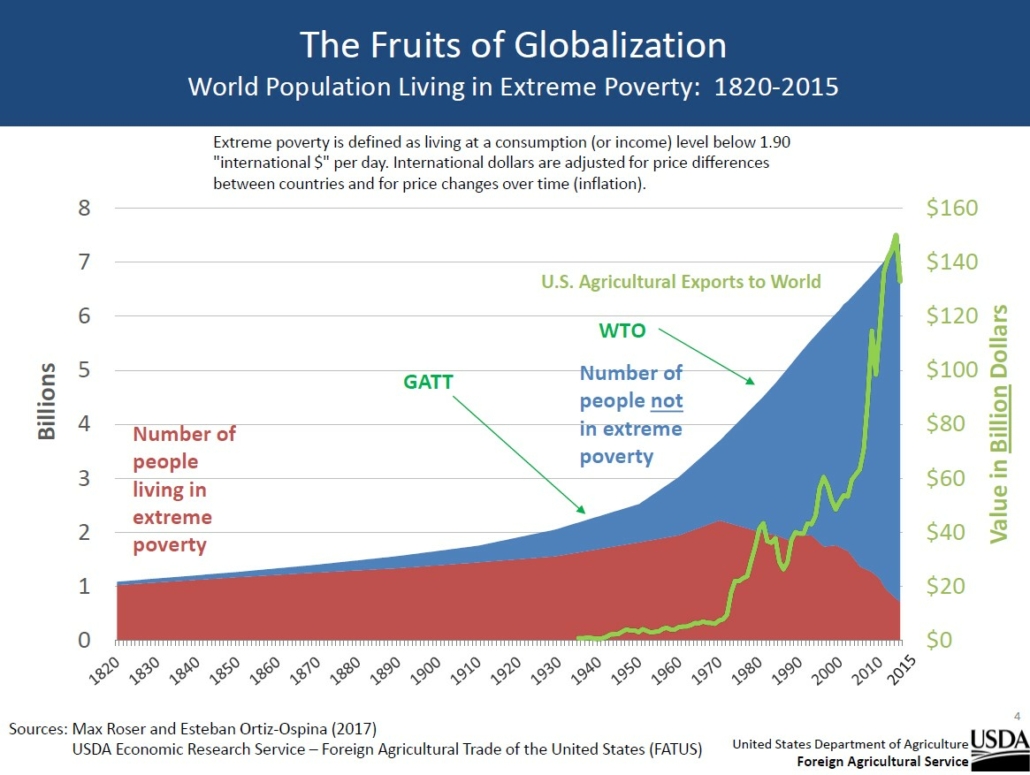

Those original rules have been critical to the expansion of U.S. agricultural trade since the WTO was formed in 1996. The chart below, shared with USW’s board of directors in early 2022 by USDA Acting Undersecretary for Trade and Foreign Agriculture Jason Hafemeister, shows the double-sided value to world economies from the WTO. By standardizing the rules of trade and reducing barriers in its initial agreement, the WTO enabled a tremendous rise in exports of U.S. agricultural products while simultaneously lifting millions of people worldwide out of poverty.

So, in looking back at another WTO Ministerial meeting, there may be much to be said about its shortcomings and the need for improvements, but history shows when countries stick to the rules and agreements, trade – and people – win.

*The U.S. Trade Representative defines SPS measures as rules and procedures that governments use to ensure that foods and beverages are safe to consume and to protect animals and plants from pests and diseases.

By USW Vice President of Policy Dalton Henry