USW Director of Trade Policy Peter Laudeman (left) chats with NAWG Vice President of Policy and Communications Jake Westlin during the recent “Washington Watch” event in the nation’s capital. Laudeman is currently in Australia to engage grain industry stakeholders in that country and explore ongoing global issues involving trade, plant breeding technologies and World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments.

U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) Director of Trade Policy Peter Laudeman is in Australia this week to engage grain industry stakeholders in that country and explore ongoing global issues involving trade, plant breeding technologies and World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments.

While a major competitor for U.S. wheat, Australia presents many opportunities for collaboration on policy initiatives that mutually impact both U.S. and Australian producers.

Laudeman will interact with researchers, government regulators, producer organizations, and private sector plant breeding and grain handling companies. His discussions will primarily be focused on the regulatory environment guiding plant breeding technologies, including transgenic and gene edited wheat. Both the U.S. and Australia regulators are reviewing applications to deregulate HB4 wheat produced by Argentinian company Bioceres.

HB4 wheat, a drought-tolerant transgenic wheat, received approval for commercialization and cultivation from Brazil in early March. Brazil joined Argentina, which granted commercialization approval to the genetically modified (GM) wheat in 2022. HB4 wheat is also approved for food and feed use in the U.S., Australia, Colombia, New Zealand, South Africa, Nigeria and Indonesia.

Growing global demand for wheat combined with persistent drought conditions that hamper production is leading the push for greater acceptance of new plant breeding technologies. Bioceres said HB4 drought-tolerance technology has been shown to increase wheat yields by an average of 20% in water-limited conditions.

USW and the National Association of Wheat Growers (NAWG) are guided by jointly approved “Wheat Industry Principles for Biotechnology Commercialization,” which lay out specific steps expected from plant breeding companies if they wish to commercialize transgenic wheat in the U.S.

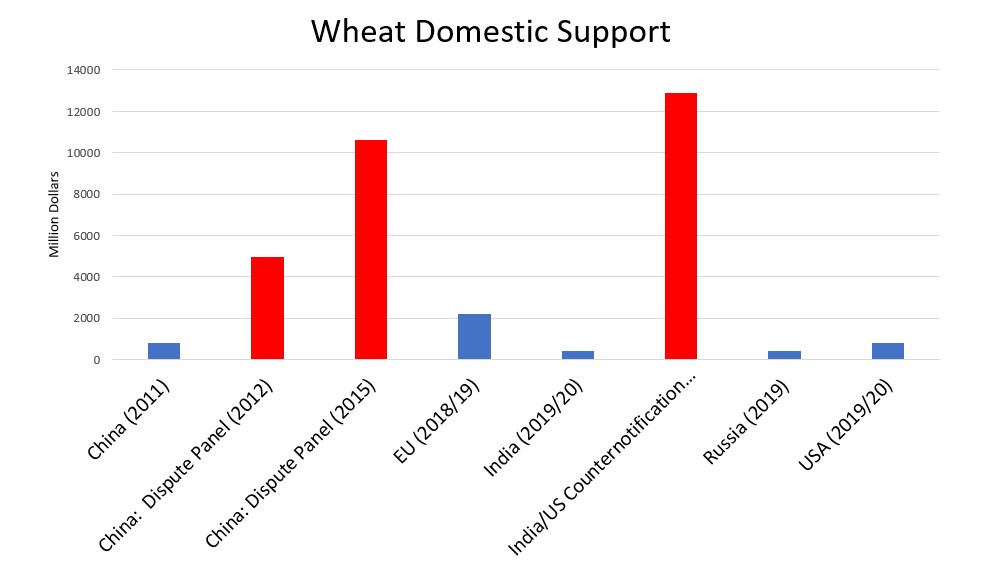

India’s oversubsidization of wheat and rice is another topic Laudeman will visit while in Australia, which has been a partner with the U.S. in holding other trading partners accountable to their WTO commitments. Australia recently joined WTO counternotification filed by the U.S. against India.