When clatter around trade policy gets noisy, Dalton Henry likes to quiet things by breaking down issues affecting the exporting of U.S. wheat into two basic categories.

“Everything has potential to be either an opportunity or a distortion,” the Vice President of Policy for U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) explained. “In general, USW’s Policy Team spends every day looking at situations around the world that impact U.S. wheat and sorting out which category they fall under. Then we work on solutions.”

Market access is a centerpiece of trade policy.

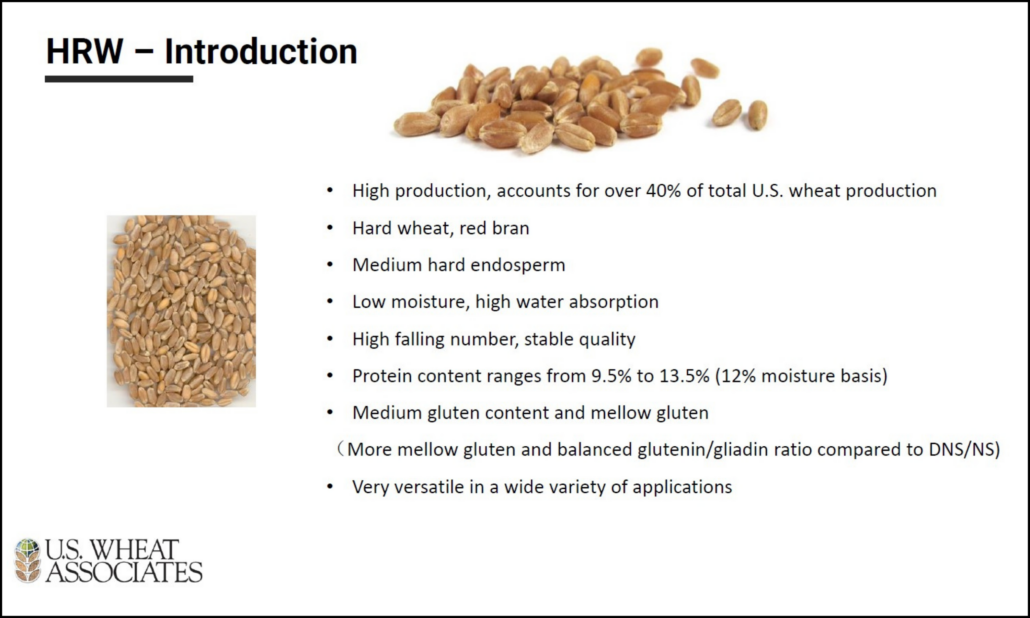

As with any agricultural product, tariffs, export barriers and other trade policies can increase the cost of U.S. wheat for the entire supply chain and customers who sit on the buying end of that chain. Ultimately, USW’s Policy Team – Henry and Director of Trade Policy Peter Laudeman – is tasked with helping smooth the process of getting wheat grown by U.S. farmers to customers around the world.

USW Vice President of Policy Dalton Henry details issues and policies facing US. wheat during his presentation at the 2022 USW/NAWG Joint Fall Board meeting in early November.

Where trade agreements do exist, the team monitors them to ensure they are properly implemented and followed. It also keeps an eye on human and environmental health regulations around the world to make sure they don’t disrupt U.S. wheat trade. And the team plays a big role in monitoring the use of wheat in U.S. international food assistance programs.

An example of a trade policy success by USW was realized about a year ago, when it teamed with USDA to show the Vietnamese government why eliminating a 3% tariff on imported U.S. wheat would help ease food inflation while benefiting Vietnamese flour millers.

Australia and Canada, the largest wheat suppliers to Vietnam, had duty-free access to Vietnam under regional trade agreements. The decision at the end of 2021 to remove the tariff on U.S. wheat also helped level the playing field in what is a fast-growing market.

Food Assistance: A Policy Team Focus

Laudeman, who joined USW in August 2022, brought with him diverse experience working for both U.S. growers and the crop protection industry.

In addition to trade policy work alongside Henry and his work on biotech and plant breeding innovation, Laudeman is providing USW with leadership on food assistance and development.

“A lot of people don’t realize our food aid markets, where the U.S. government is purchasing and donating commodities, makes up a Top 10 U.S. wheat export market,” Laudeman said. “The USW Policy Team makes sure that that all regulatory mechanisms are functioning properly when we send U.S. wheat food aid, either as emergency support or on a developmental basis.”

In his role, Laudeman also spends a lot of time working closely with professional economists. As a believer in the notion that trade policy is inherently economics-based, it’s a natural connection for him. He regularly monitors USDA databases and other data sources to assure USW can analyze trade data.

It’s not all numbers and calculators, he emphasized.

“My role is very relationship-based and USW’s relationships with other commodity organizations are vital because many times we need a strong agricultural coalition to work on some of these trade issues that impact us,” he said.

U.S. Wheat Director of Trade Policy Peter Laudeman reviews the effect of Turkey’s flour export tactics on U.S. wheat exports at the 2022 USW/NAWG Joint Fall Board meeting.

Preparing for 2023 Issues

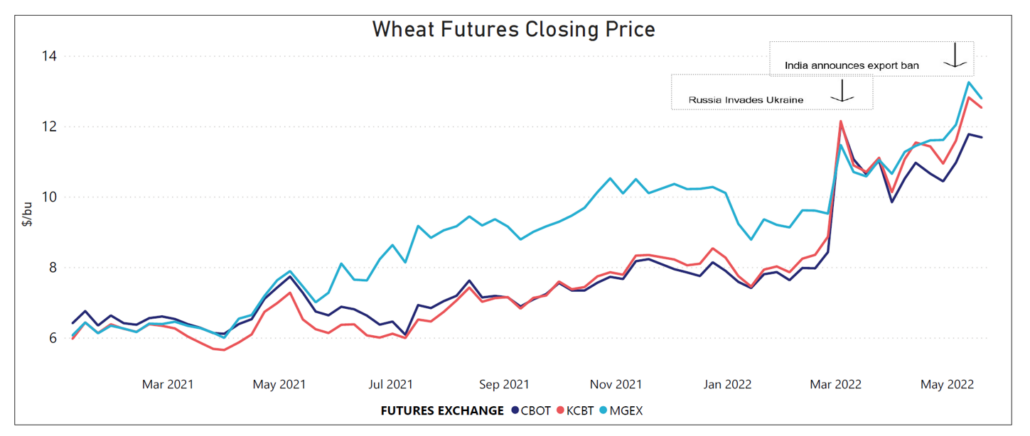

While the entire U.S. wheat industry continues to keep an eye on the Russia-Ukraine conflict and its affect on trade, USW’s Policy Team is also focused on a handful of other countries and ongoing situations that could have an impact on wheat trade.

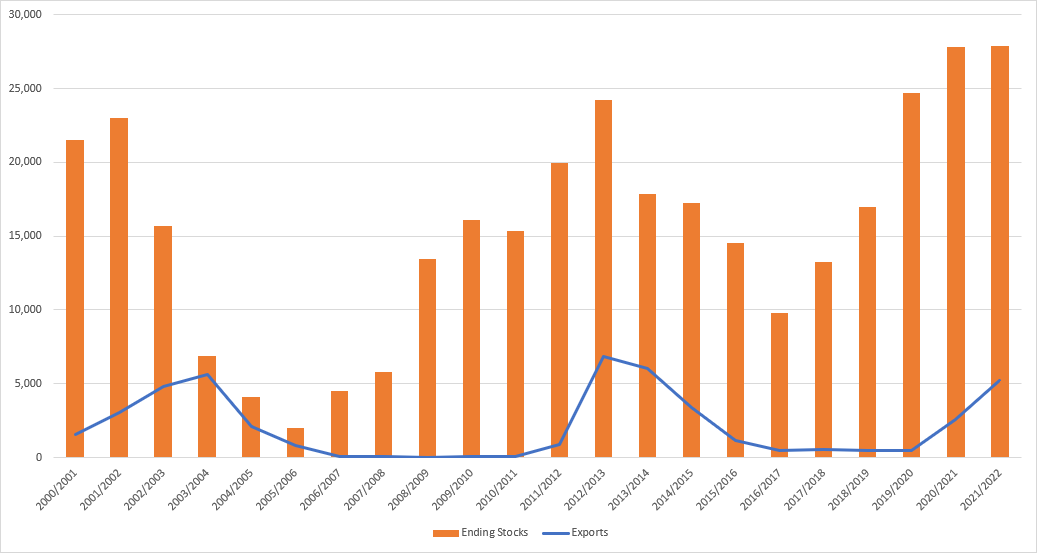

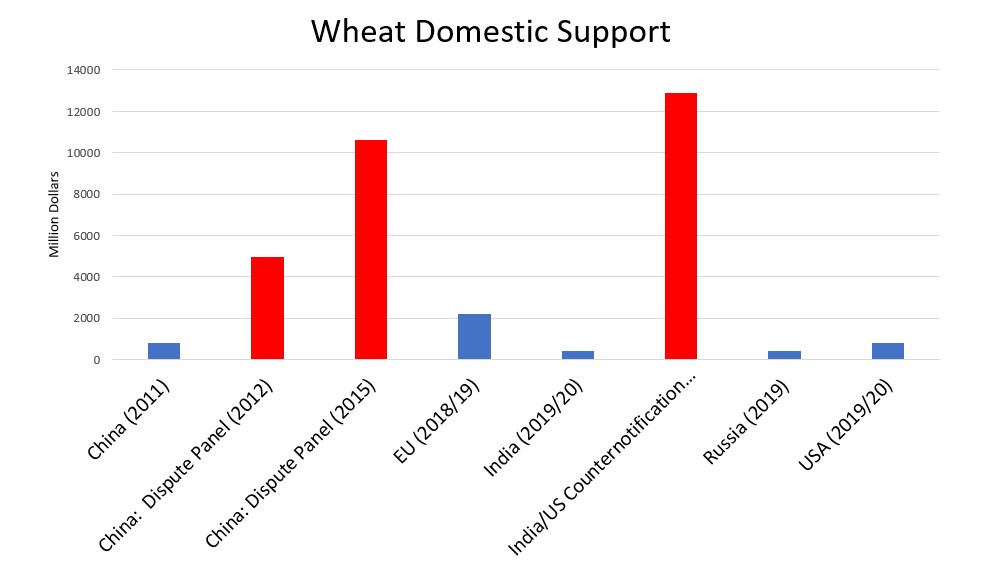

“Where are the big distortions in the global wheat market right now? China continues to be problematic, even though we have seen tremendous progress in how they are running their tariff rate quota system,” Henry notes. “We still have challenges with their domestic subsidies for a system that produces a larger and larger wheat crop year after year. China continues to hold more than 50% of the world wheat stocks domestically, and that weighs heavily on global wheat prices.”

India’s domestic price support programs also stands out as a red flag in the coming year, Henry noted. He listed Turkey is a third “distorter” because of its on-going policies that encourage dumping of wheat flour and under-reporting data to the World Trade Organization.

At the top of Henry’s 2023 “Wish List” is renewal of anti-dumping duties imposed by the Philippines government on Turkish flour. If the duties are not renewed, the Philippines milling industry will be hurt and up to $100 million in U.S. wheat imports could be lost.

And not going away in 2023 are non-tariff barriers to trade, which represent the fastest-growing barrier impacting wheat trade, according to Henry.

Examples of non-tariff barriers are rules like maximum residue limits (MRL) on pesticides and limits on weed seed species or insects. Many sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regulations are critically important to protecting plant and human health, but many countries are using them to protect domestic producers – creating obstacles to trade for U.S. wheat.

Breaking down those obstacles is the goal.

“Trade policy work requires us to be in constant contact with a wide range of regulators and non-government organizations,” said Henry. “Ultimately, the goal is the same – to make sure we are doing everything we can to help keep wheat trade flowing between the farmers we represent and our values customers around the world.”