As part of its fiscal year 2021 Food for Progress Program, USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA-FAS) recently announced an award of 300,000 metric tons of U.S. hard red winter wheat to Sudan. The award is worth an estimated $120 million.

As wheat is a dietary staple in many diets, U.S. wheat has a long history of playing an important role in U.S. food aid programs. U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) and the farmers our organization represents welcome this award and are proud to play a part in helping the Sudanese people.

Food for Progress is an international development program at USDA-FAS that was authorized in the 1985 Farm Bill to help developing countries improve their agricultural industry through the monetization of donated commodities. The donated commodity is most often sold into the local market, with the proceeds funding an agricultural development program or addressing a specific need in that country.

Ethiopia Feed Program

Several Food for Progress programs have used wheat in recent years to help those in need. U.S. wheat was purchased to support Ethiopia’s livestock-feeding industry through the Feed for Enhancement for Ethiopian Development project (FEED). FEED monetized the wheat to supply a challenged local flour mill to secure supplies. The bran byproduct from processing the wheat was sold for livestock feeding in return, benefitting the FEED program.

Water Development in Jordan

Under a different Food for Progress program, wheat was monetized to Jordan for water development projects, including drilling deep wells, water waste treatment facilities, and dams for the purpose of agricultural improvements in Jordan. This area of the world has diminishing water supplies and limited infrastructure, so projects like these help improve agricultural development to countries in need.

The bulk carrier African Sunbird with U.S.-origin hard red winter wheat at the Port of Aqaba, Jordan on Aug. 29, 2017, during the vessel delivery ceremony under the USDA’s Food for Progress Program. Photo by USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.

Although most U.S. food aid is sent under the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)’s emergency feeding programs, the Food for Progress program is unique in that it was established to pair the use of U.S. commodities with funding for agricultural development programs in developing countries. Programs are either government-to-government or through awarded proposals from non-government organizations (NGOs).

NGO Role

Once the government awards a program to an NGO, it implements the development program in one of the countries FAS identifies as priorities each year. The Sudan Food for Progress program is slightly different because it will not impact a specific agricultural development program in country. Instead, the wheat will go to mills then be sold as flour because the country faces a short supply of wheat.

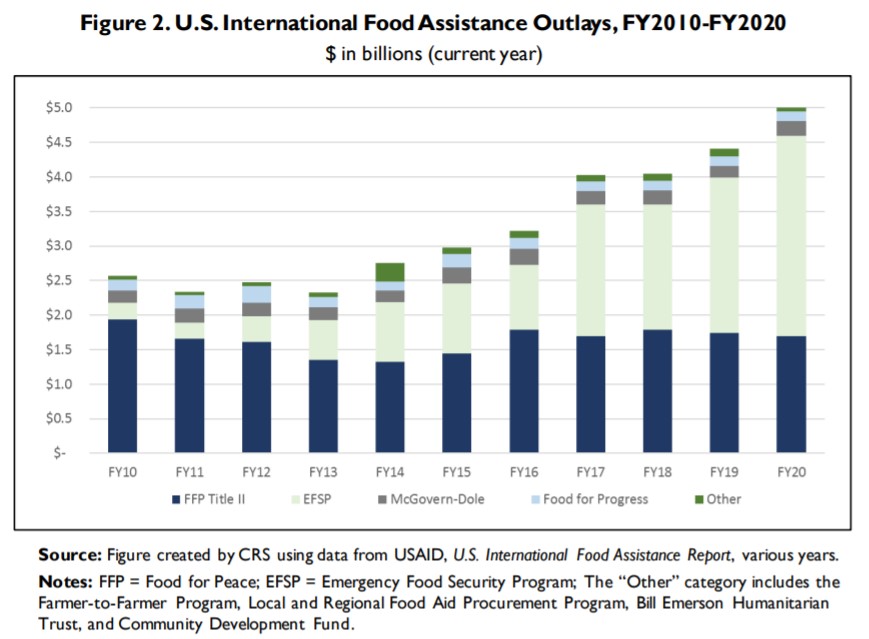

Data from U.S. Congressional Research Service.

USW values its partnership with USDA-FAS and looks forward to continuous promotion of high-quality U.S. wheat abroad to our valued customers – and to helping improve the lives of the neediest people through the Food for Progress program and other opportunities.

By Shelbi Knisley, USW Director of Trade Policy