Kansas State University has launched a project that will bring together two of its strongest agricultural programs under one roof.

The university held a groundbreaking ceremony on May 17 for the Global Center for Grain and Food Innovation, to be located just off the corner of Claflin Road and Mid-Campus Drive. The new building is estimated for completion in Fall, 2026.

It will also bring faculty and staff from the departments of animal science, food science, and grain science together, allowing them to work side-by-side on more projects.

Enhancing Milling and Bakery Science Education

K-State’s Department of Grain Science and Industry offers the country’s only undergraduate degrees in milling science, bakery science and feed and pet food processing – and in fact, is one of only a few in the entire world to do so. The department reports a 100% job placement rate in those degree programs.

Hulya Dogan, interim department head for grain science, said the Global Center for Grain and Food Innovation will be the new home for her department’s faculty and staff, replacing the aging Shellenberger Hall. On May 20, K-State announced that Dr. Joseph Awika has accepted the position of Grain Science and Industry department head.

For students, Dogan said, the new building will contain “the latest technologies so that they are able to enter the workforce immediately after graduation.”

Sharing space on the K-State campus not far from where the new Center will be located is the Kansas Wheat Innovation Center, built by the Kansas Wheat Commission, through the Kansas wheat checkoff, to get improved wheat varieties into the hands of farmers faster. It represents the single largest research investment by Kansas wheat farmers in history. IGP Institute and the Hall Ross Flour Mill are also part of the K-State training and teaching services, familiar to many overseas U.S. wheat buyers through U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) export market development activities.

Ambitious Plan

Ernie Minton, the Eldon Gideon Dean of K-State’s College of Agriculture, said the center is the third groundbreaking in the university’s Agriculture Innovation Initiative, a multi-year push to upgrade and expand facilities in grain, food, animal and agronomy research. When completed, the Agriculture Innovation Initiative is anticipated to top $210 million raised from a combination of state, private and university funds.

The Global Center for Grain and Food Innovation “is part of an ambitious plan to make Kansas State University the Next-Generation Land Grant University,” Minton said. “We want to be the example of what a land grant university should be in the 21st century.”

Ernie Minton, the Eldon Gideon Dean of K-State’s College of Agriculture, provides remarks during the groundbreaking ceremony for the Global Center for Grain and Food Innovation, May 17 in Manhattan, Kansas.

K-State President Richard Linton called May 17 “a big day for the College of Agriculture, a historic day for K-State, and a transformational day for Kansas agriculture and our agriculture and food industry stakeholders.”

“Get ready,” he said. “Things are going to look and feel different at Kansas State University. Our agriculture impact locally and globally will reach new heights because of this project.”

Linton pointed to the entirety of the Agriculture Innovation Initiative, which will create four new buildings and three remodeled spaces.

“These facilities will support cutting-edge research and learning,” Linton said. “We will have interdisciplinary lab spaces and areas dedicated to helping foster partnerships with industry. Students can expect larger, more accessible classrooms outfitted with the latest technologies and suitable for remote learning. There will also be unique learning spaces, like the arena pavilion, a pilot plant and a test kitchen.”

Learn more about K-State’s Agriculture Innovation Initiative at www.k-state.edu/ag-innovation.

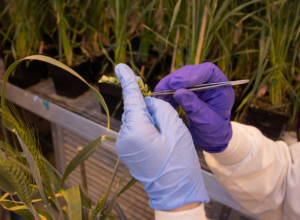

From uncovering the dense nutrients for improving wheat as a food crop to bringing in trails from wheat’s wild relatives or improving agronomic traits, Gallagher told Harries there is still more to unlock in the wheat genome.

From uncovering the dense nutrients for improving wheat as a food crop to bringing in trails from wheat’s wild relatives or improving agronomic traits, Gallagher told Harries there is still more to unlock in the wheat genome.