Overall, U.S. wheat farmers are certain they produce some of the highest quality milling wheat in the world and want to compete on that basis freely and fairly. That desire is being challenged in unique ways right now by trade policies and global reactions that have never been a part of the world wheat market. To express the challenges of these policies on farmers and the rural community, the National Association of Wheat Growers (NAWG) this week arranged for one of their members to testify before the U.S. House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee’s Trade Subcommittee. We want to share that testimony here:

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Committee. My name is Michelle Erickson-Jones and I am the Co-Owner of Gooseneck Land and Cattle from Broadview, Montana. I also currently serve as the President of the Montana Grain Growers Association, am on the Board of Directors of the National Association of Wheat Growers and a member of Farmers for Free Trade. As a fourth generation farmer, it is my honor to testify today on the impacts of tariffs on my farm, my industry and most importantly my community that depends on trade for its livelihood.

American agriculture is a tremendous global marketing success story. We export 50 percent of our wheat and soybeans, 70 percent of fruit nuts, and more than 25 percent of our pork. We are also the top exporter of corn in the world. Exports account for 20 percent of all U.S. farm revenue and we rely on strong commercial relationships in key markets including Canada, Mexico, Japan, the European Union and, of course, China – the second largest market for U.S. agriculture, accounting for nearly $19 billion in exports in 2017. U.S. agriculture exports also support over 1,000,000 American jobs. As such, trade is critically important to the U.S. economy and our rural communities.

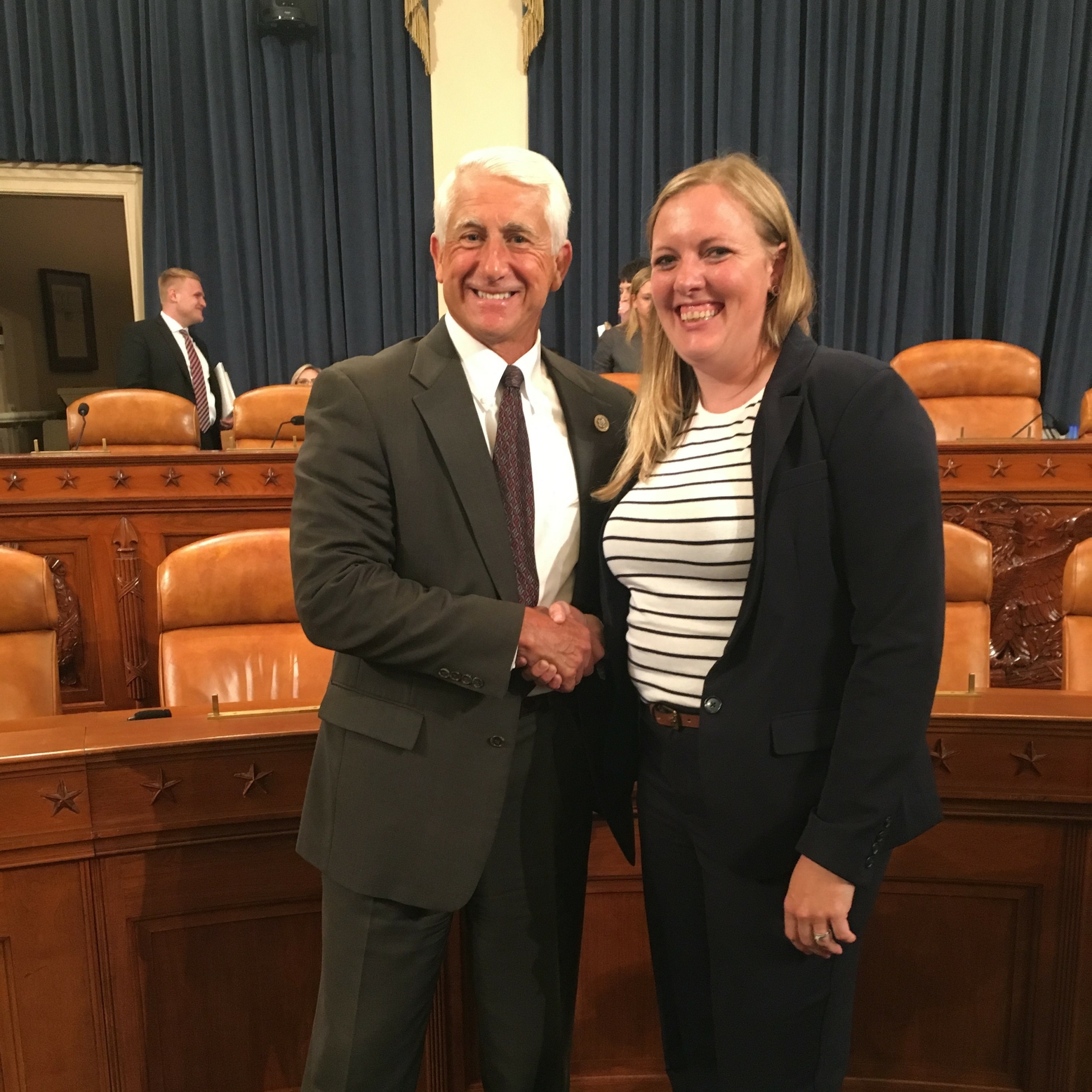

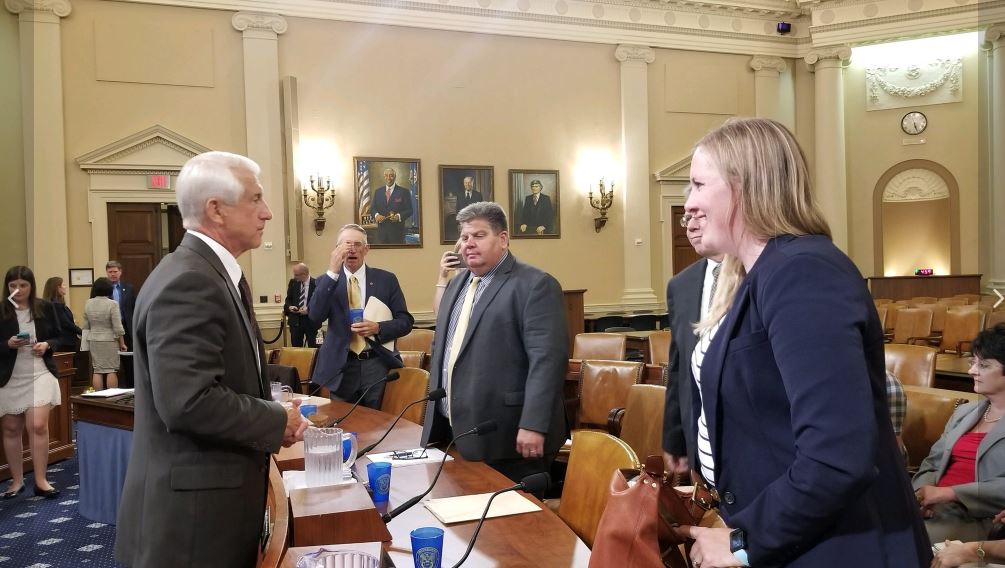

Rep. Dave Reichert (R-WA) and Michelle Erickson-Jones.

Farmers across the country depend heavily on the ability to sell our commodities to foreign consumers. We are painfully aware of the prevalence of unfair trading practices used by some countries and we support the Administration’s interest in finding solutions to tariff and non-tariff barriers that impede fair trade. But what I’d like to share with you today are some examples of the impact of tariffs imposed by our own Administration and by the retaliatory tariffs levied by our trading partners. These impacts are felt by farmers such as myself throughout our supply chain, from higher input costs to reduced exports and lower market prices.

In May, I testified at Section 301 hearing at the International Trade Commission. As I said then and believe more strongly than ever now, “while many rural American families are optimistic about economic growth under the current Administration, there is mounting concern among farmers about trade policies that would reduce access to the export markets they depend on.”

There have been very few issues in my career as a farmer that have caused me to lose sleep. But these tariffs are one of them. I’d like to share some of the effects that have directly impacted my farm and family.

The first wave started at the time the Administration imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum. For me and farmers across the country that translates into increased costs of capital investments. For example, earlier this year we priced a new 25,000-bushel grain bin to increase grain storage capacity on our farm. The price was 12 percent higher than an identical bin we had built in 2017.

As we weighed our options, the bid on bin #2 expired, so we sought a second bid. This bid was 8 percent higher than the one we received just a few weeks prior – a 20 percent increase total in the cost of the same steel product in just one year.

The bin company attributed the difference in the final bin cost to a significant increase in their cost of steel. I learned that their domestically sourced steel suppliers had increased their prices to match the price of imported steel which was subject to an additional 25 percent duty when imported. As a result of this dramatic cost increase and volatility in the market, we abandoned our grain storage expansion project. The implications of that decision not only harmed my operation, it also hurt my community: a small local construction company lost a project, a U.S. grain bin company missed a sale, and a domestic steel company had one less shipment to send out of their factory.

Another unexpected outcome is something we are living through right now. Back in January, we built cattle guards for several capital improvement projects we had planned for later in the fall. A neighbor saw the finished product and asked to buy several from us. We agreed because we thought we would be able to utilize the profits for other investments. Last week I priced the steel needed to replace the cattle guards I had sold. To my shock, the price of steel had increased 38 percent – evaporating our profits. To make matters worse, now we will no longer break even on the project.

These scenarios are playing out across the nation, particularly the states that depend on agriculture. These states depend on healthy agricultural commerce for a robust economy. As our profits evaporate and our ability to spend on rural main street businesses or take weekends away decreases, our other top economies, including tourism and manufacturing, are negatively impacted as well.

While one singular example is a small sum of money in the big picture, adding up those small singular examples shows the real and substantial increase to agriculture and rural main street.

There are countless examples in Montana, where last summer, large portions of my state were on fire. Just imagine the cost or replacing fencing or other equipment with prices increasing by double digits – at a time of record low prices for agriculture commodities. The impacts on our input costs coupled with increased market volatility and lower farmgate prices have further reduced our already slim margins. According to the USDA Economic Research Service net farm income is expected to drop to a 12-year low, down 6.7 percent from 2017.

Now allow me to further illustrate the impact of tariffs on our topline – sales – especially in an industry that exports $450 million in wheat to China annually, $65 million of which was from Montana. China is the world’s largest wheat consumer, with a significant trade opportunity in their market. In market year 2016/2017 China was our fourth largest customer, however when China placed a 25 percent retaliatory tariff against U.S. wheat not one new shipment has been purchased from the United States since March, and the last shipment arrived in June.

Wheat growers also understand that China hasn’t been keeping to their trade obligations they agreed to when they joined the WTO (World Trade Organization), and as such the United States has two cases against China for their domestic support programs and their TRQ (tariff rate quota) requirements for wheat, rice and corn. We applaud the Administration for moving forward with these cases and believe this is the proper course of action to hold our trading partners accountable to their trade commitments. We do not, however, support the tariffs which have already hurt many farmers across the United States through both the tariff retaliation and domestic decisions as I have outlined.

For Montana, other commodities are also being hurt. Our producers are already suffering from the 25 percent import tariff on American pork and are bracing for the impacts on beef. Mexico has also targeted these two sectors in response to the steel tariffs.

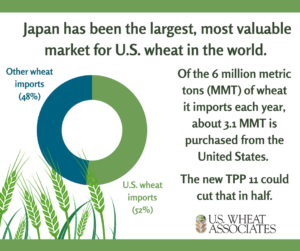

In addition, these markets that we’ve been growing for decades could be lost to our competitors who do not have tariffs against their products, a fate that could last for years or decades to come. The same can also be said by not seeking or joining new trade agreements, for example when CPTTP (Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership) is implemented our Canadian and Australian wheat competitors will gain a price advantage in Japan against U.S. wheat, potentially losing our largest wheat market.

Currently farmers like me are not only struggling to ensure this year’s crop is profitable, but we are also concerned about the long-term impacts to our valuable export markets. For young and beginning farmers like me the stakes are even higher. We are often highly leveraged, just establishing our operations, as well trying to ensure we have access to enough capital to successfully grow our operations. Increased trade tensions and market uncertainty makes our path forward and our hopes to pass the farm on to our sons less clear. I hope to pass my farm to my sons and as such urge you to consider the tolls these tariffs will have on my operation and how it impacts that possibility, and many other family farms, as outlined in my testimony.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today.