Look at a line graph that tracks freight markets over the last two years and you may mistake it for the very waves the vessels traverse on the open ocean. Up and down the vessel goes, and so have the rates.

The Baltic Dry Index (BDI), an assessment of the average cost to ship raw materials such as grains, coal and iron ore, hit a 13-year high on October 7 at 5,650, yet three weeks later, it climbed down 28% to 4,056 on October 27.

Disruptions and More

The effects of COVID-19 have turned the traditional flow of sea commerce upside down. And as economies reemerge from the pandemic-induced lull, logistic obstacles have abounded. “Global Supply-Chain Problems Escalate” and “Cargo Piles Up at Ports” are just two of the headlines outlining the shipping industry’s challenges. Disruptions to the supply chain, port congestion, and logistical challenges all add to the run-up in freight markets.

Grains, including wheat, are traditionally shipped using bulk carriers like Panamax, Handymax and Capesize vessels that contain large cargo holds to segregate grains. Cargo ships, the more familiar vessel for the trans-ocean shipping of retail items, only carry small volumes of grain. However, as extraordinary times created the need for more extraordinary efforts, the massive U.S. retailer Walmart recently chartered a dry bulk cargo ship to carry merchandise to circumvent global supply chain disruptions. Other retailers may do the same as the holiday season approaches.

Idled Vessels

That would not be a bargain because 16% of the world’s dry bulk fleet is waiting to unload at various ports around the world, with 6% of those vessels waiting at Chinese ports. The inefficiencies caused by loaded vessels idling outside ports translate directly to tighter supply despite higher demand and, thus, higher prices. Dry bulk shipping rates were below $20,000 per day last January but rates, led by Capesize vessels, hit $85,000 per day in September. Grain buyers still must ship wheat and pay the higher prices, pushing up all rates across dry bulk carriers.

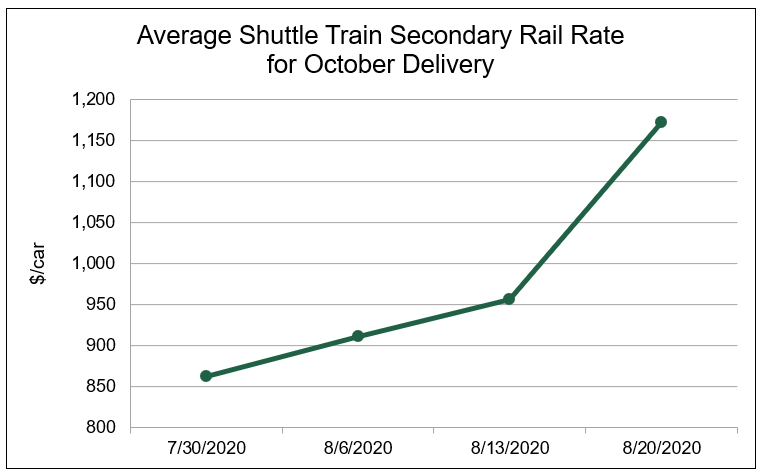

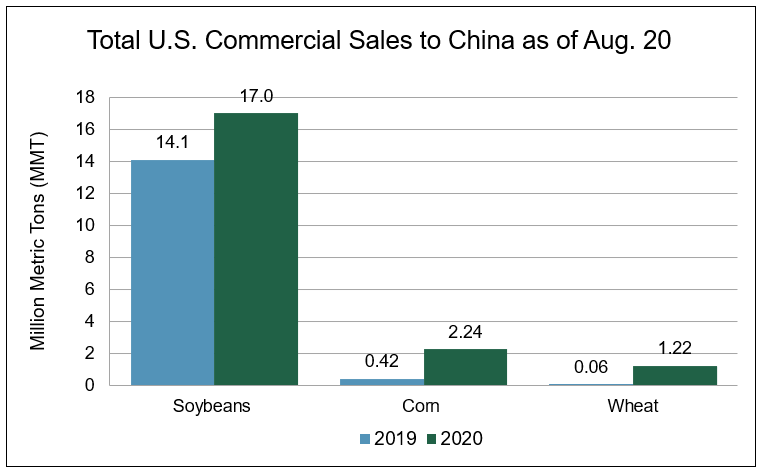

Global import for grain has also increased year-over-year. For example, China’s demand for grains has equated to around 25% of worldwide demand. Looking back, in the mid-2000s, the number of dry bulk carriers outweighed the demand for such vessels. However, an economic boom in China starting around 2006 saturated the dry bulk market leading to greater demand and a soaring BDI. Eventually, shipping companies added to their fleets, and the added capacity helped freight markets to stabilize. Then the global financial crisis reduced the demand for such vessels and slowed shipbuilding. Now a new spike, starting in 2020, has driven demand up again and daily rates for dry bulk shipping. The nearby market remains high while the forward market is much lower, creating a significant inverse. Exporters who need to ship now must pay the higher prices.

Doubled

Importers in South Korea, the fifth-largest U.S. wheat customer, based on a 5-year average, has seen freight rates double from US$40 per metric ton (MT) in 2020 to around US$80 per MT dollars today, said C.Y. Kang, Country Director for U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) based in Seoul. Kang also noted that the BDI Index in 2020 averaged 1,064 while this year it has averaged 2,941, a 176% increase. Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer, has suspended the 15% price advantage it offered the state shipping line as GASC, the Egyptian state commodities buyer, tries to find ways to lower the overall cost of wheat imports.

High oil prices are also keeping freight rates elevated. On Tuesday, oil futures hit their highest levels since 2014 but started to slump Thursday, hitting their lowest level in two weeks at $80.58 as U.S. crude inventories rose more than expected. One market analyst said that energy prices are unlikely to weaken for the remainder of the year as supply remains restrained, but demand returns to the 5-year average. Oil sold for around $15 per barrel in April 2020 versus today, a 431% increase.

Seeing the Top?

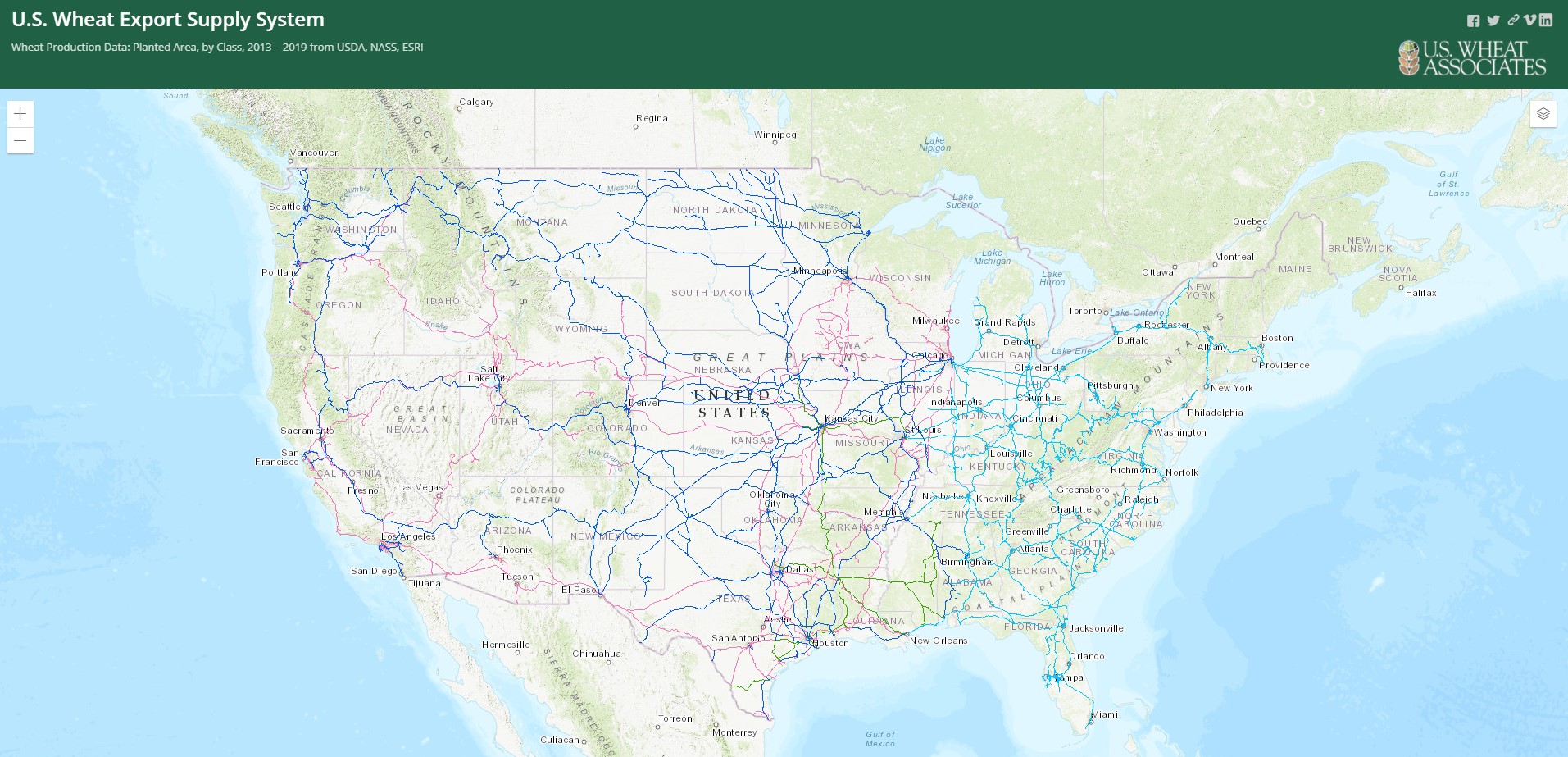

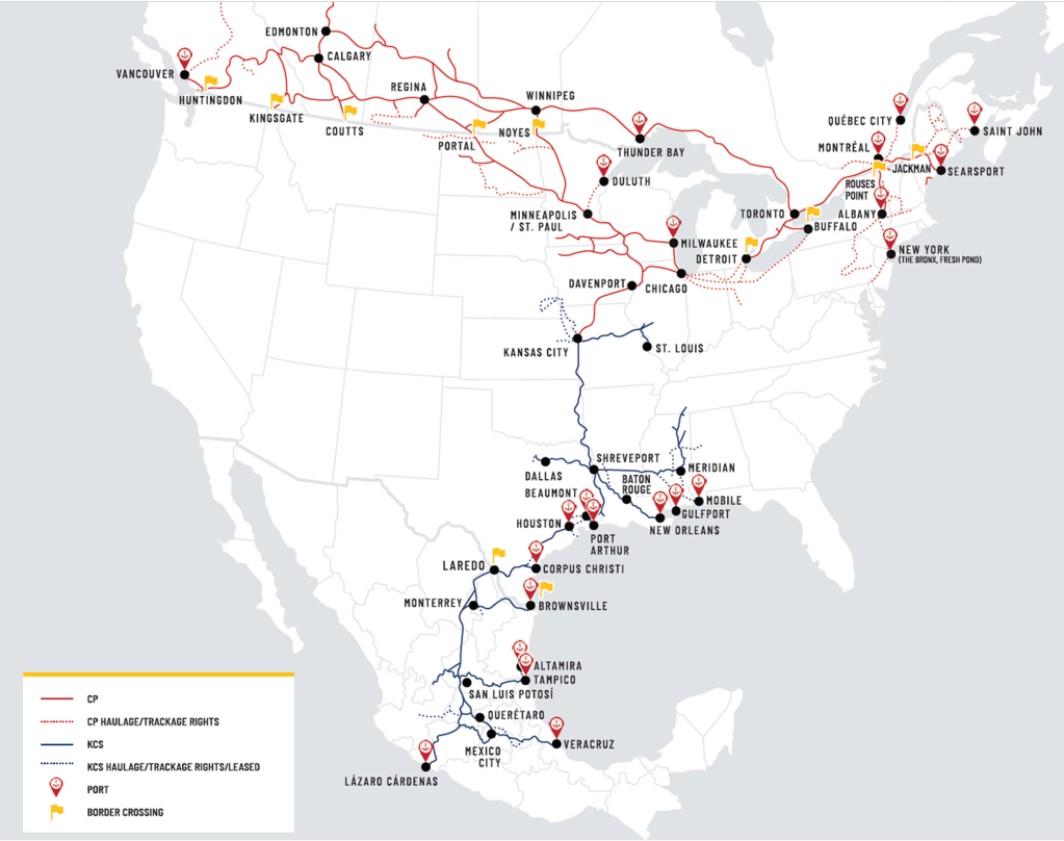

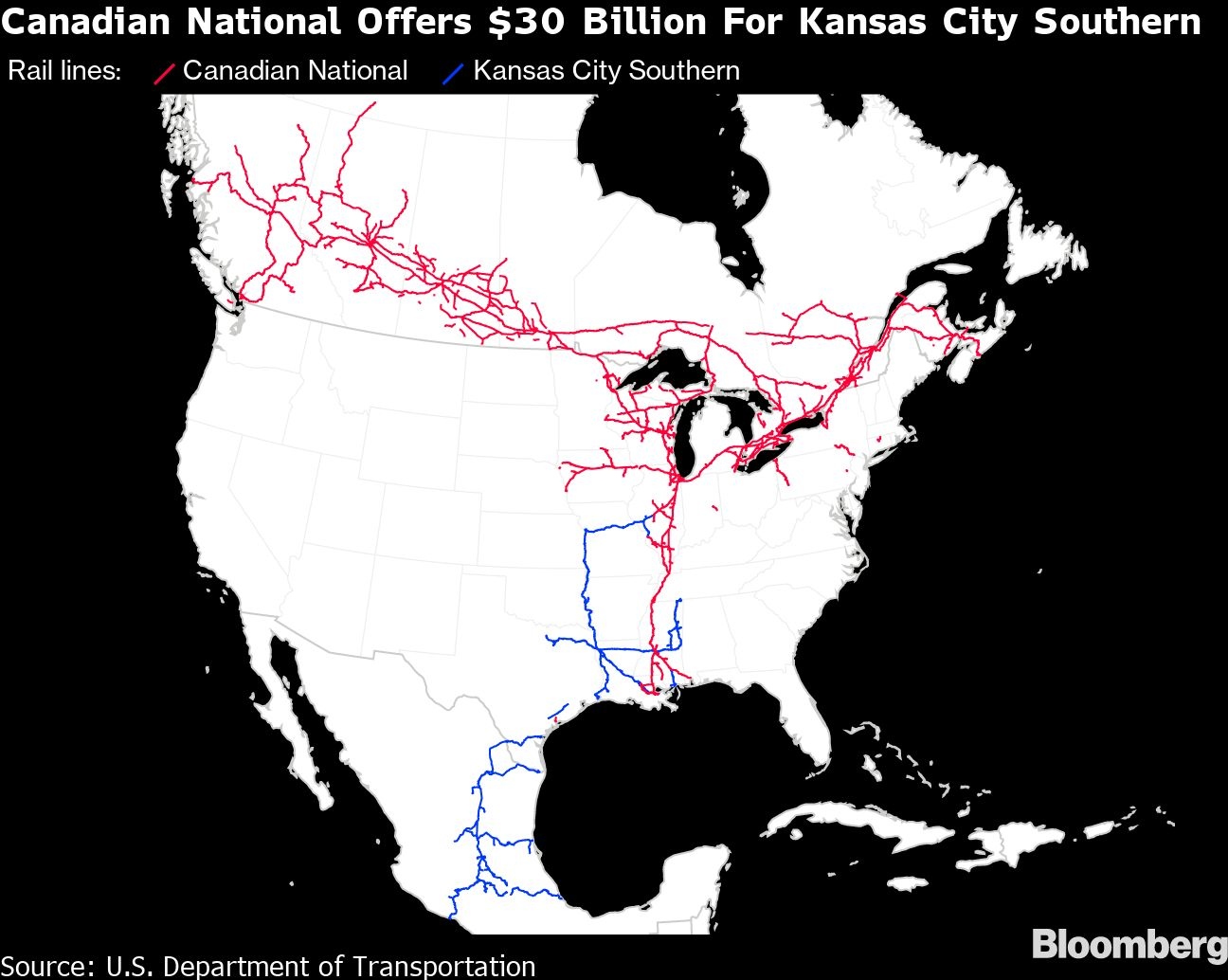

Jay O’Neil, a commodities consultant, has outlined all today’s obstacles in the export freight supply chain in a video presentation that will be available to U.S. wheat customers in early November. On top of long lines at ports, there is a shortage of vessels, containers, skilled labor at ports, warehouse workers, a 30% shortage of truck drivers, railroad cars and even chassis to attach containers to train cars. In his presentation, O’Neil says that despite the logistical mess, which could extend into mid-2022, the dry bulk market is likely to have hit its top.

As these circumstances change globally, logistical headaches may ease as more workers return and more consistent patterns resume. For now, though, the tight supply of vessels and the consistent appetite for grains is helping keep the global dry bulk business at historic levels.

Stay up to date on U.S. wheat market information at https://www.uswheat.org/market-information/.

By Michael Anderson, USW Market Analyst