Excerpts from “How Does Trade Affect Me?,” the March 13, 2018, blog entry in “Big Sky Farm Her. Navigating Life as a Montana Farmer” by Michelle Erickson-Jones.

Trade has become an area I am increasingly interested in studying as well as advocating for. In order to advocate for trade, a notoriously complex, slow moving, and polarizing policy issue, I needed to convey why trade is important to me. Why it is important to our farm, our state, and our national agriculture economy.

Why is trade important to our farm?

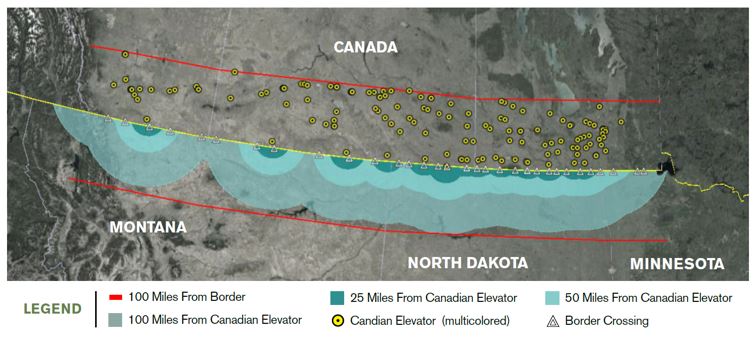

We rely on export markets to provide us with consistent outlets for our grain. Unfortunately, there is not enough demand domestically for wheat. Also unfortunately, we do not necessarily have the ability to change the crops we raise for numerous reasons. We pride ourselves in our ability to produce high quality hard red winter and spring wheat that is in high demand in the Asian [and other] markets. They need/want our wheat to produce products that are popular in those markets. We want to maintain these markets as an outlet for our production.

My personal feelings on trade and its impact on our operation are that current trade policy and the shift towards protectionist policies keep me up at night. Never before have policies and government regulations caused me to lose sleep. I lose sleep [now] because I know agriculture trade is incredibly competitive, our ability to increase market share is limited, trade policy is incredibly slow to develop (and requires at least two willing partners), and because I know every day that goes by under our current policies risks our market share. It risks decades worth of work done by individual farmers through our commodity commissions, trade negotiators, other government officials and others.

Like most farmers I dream of the day my children take over the farm, I dream of giving them a better agricultural economy and a better operation than I started with (not that there was anything wrong with our operation but there is always room for improvement). Our current trade policy puts that dream at risk.

Why is trade important to our state? In 2016 Montana exported $1.6 billion in agricultural products. Agriculture is also the number on economic driver in Montana. We depend on our export markets to maintain that economy for the state.

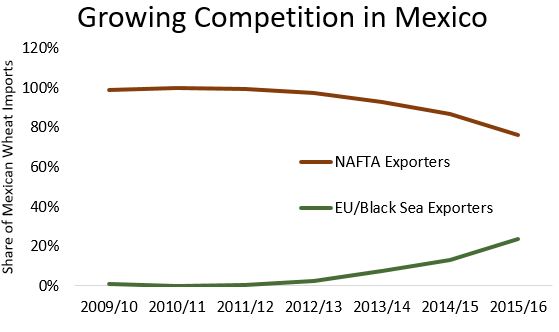

Montana has a proud history of producing high quality wheat, barley, and beef among many other products. These products are in high demand across the globe, largely because of the high quality. We produce some of the highest quality hard red wheat (both winter and spring) as well as durum in the world. Many of the most competitive markets for these products demand Montana raised products. The Montana Wheat and Barley Commission (MWBC), in conjunction with [U.S. Wheat Associates] has spent decades developing relationships with Japanese buyers to ensure we can supply them with the quality they demand. The Montana Wheat and Barley Commission has traveled to Japan countless times as well as welcoming their trade teams to our farms. Despite their hard work, their ability to attract and maintain those relationships hinges on our free trade agreements. The TPP 11 agreement without the United States gives Canada and Australia a $65 per metric ton discount compared to U.S. sourced wheat; this is a tariff reduction that we will not be able to overcome, despite years of market building.

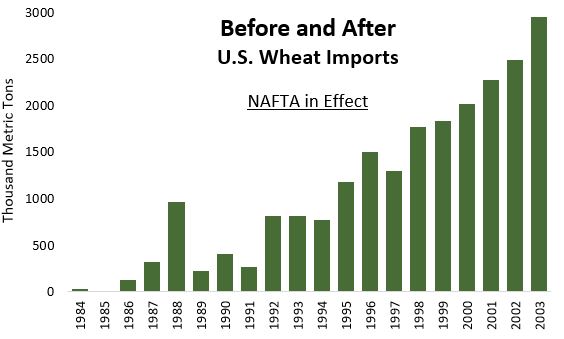

Why is trade important to our country? Agriculture trade has been growing exponentially over the past 50 years. So much so in fact that we have had a trade surplus in agricultural goods for the past 50 years. Across the nation agriculture maintains our rural economies and creates vital jobs throughout our communities. Trade policy throughout the past several decades has opened up new markets for agricultural exports, increased access in existing markets, and lowered or eliminated various tariffs and technical barriers to trade. Opportunities for improvement still abound; however, the benefits far outweigh the drawback for the agricultural community.

The increase in market access and increase in economic activity has been a significant driver in the improvement of our rural economy. Unfortunately, that rural economy continues to be under threat, a threat that risks significant economic impacts, as well as a domino effect that impacts every facet of our economy.

In conclusion, I have become passionate about international trade, I am passionate about the agricultural industry and our export partners, and I am passionate about the future of our industry. We depend on trade to maintain our export markets, ensure we have the ability to pass on our farmers to a future generation, and to ensure the rural economies stay strong for decades to come. I also understand trade is not perfect. International trade, bilateral agreements, and multi-nation free trade agreements will always have winners and losers. It is a difficult situation to deal with, it is delicate to advocate for, and it is a fact that does cause me great concern. It is also increasingly difficult to stand by and watch protectionist trade policies risk the future of agriculture and more importantly risk the future of my own farm.

Agriculture, particularly the wheat and barley industry, depend on maintaining our current market access, increasing access to new markets through free trade agreements, and improving our current agreements. Trade does not thrive on protectionism and uncertainty.

Michelle Erickson-Jones is a 4th generation farmer in South Central Montana, married to a 4th generation Montana rancher. They are raising two little boys who hopefully will be the 5th generation on their farm. The family raises wheat, malt barley, safflower, sunflowers, corn, alfalfa, forage grains, and maintains a small cow/calf operation. Michelle is the current president of the Montana Grain Growers Association but notes that all views expressed in her blog are her own. She recently worked with Farmers for Free Trade to record a national television ad focused on the importance of trade.