Name: Adrian “Ady” Redondo

Title: Technical Specialist

Office: USW South Asian Regional Office, Manila

Providing Service to: Republic of the Philippines and Korea

Growing up on his grandparents’ small farm in the Philippines province of Batangas, U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) Technical Specialist Adrian “Ady” Redondo learned that hard work is a great motivator.

“My father was away working in Saudi Arabia, and my mother worked as a midwife, so my three sisters and I spent our childhood helping our grandparents raise chickens and grow rice and corn. I learned that life is hard, and you don’t get to eat if you don’t sweat,” Redondo said. “But my grandparents also encouraged me to do well in school and be successful for them because they had to work on the farm with their parents to make ends meet instead of getting an education.”

The wisdom of grandparents helped set Ady Redondo on a path toward education and a career in food technology. In the top photo, his Grandmother Barbara (right) joined Redondo (far left), his mother Paz, younger sisters Anna Rose and Angelica, and a friend at a Flores de Mayo prayer service at church. In the bottom photo, his Grandfather Miguel holds Redondo surrounded by neighbors and friends. Redondo said his grandfather fought to get him in first grade even though he was too young: “He insisted I was just as smart as everyone in the class…and they accepted me.”

At his elementary school, lessons about a Batangueño hero added inspiration to Redondo’s interest in science.

María Y. Orosa was from the same hometown as Redondo’s mother and was considered the Philippines’ first female scientist. She invented the palayok oven to help families bake without access to electricity and developed recipes for local produce, including a banana ketchup formulation that became a favorite Filipino condiment and cooking ingredient. Orosa also used her knowledge of food technology to help save prisoners in World War II by inventing soyalac, a protein-rich powder from local ingredients, that she smuggled into the prison camps. Then, tragically, Orosa was killed in an Allied bombing raid.

Statue honoring María Orosa, Historical Park and Laurel Park, Batangas Provincial Capitol Complex. Photo copyright By Ramon F. Velasquez.

At home, Redondo had started cooking rice and eggs by the age of seven, and his interest in food and the sciences grew. He was valedictorian of his elementary school class and Salutatorian of his high school class. Once again, his grandparents were the catalyst for his next chapter.

The friendly competition helped fuel Redondo’s very successful high school education and prepared him for an excellent university. On the right, Redondo and his mother, Paz, with classmate May and her mother, Apolinaria, at a high school awards ceremony. On the left, Redondo at his 1997 high school graduation (as Salutatorian) with classmates (L-R) Cecilia, his cousin Norma and Cecil. “I hung out with them at lunch because they always had nice snacks and desserts, and the conversations were fun,” Redondo said.

“My grandparents always talked with respect about someone who graduated in agriculture from the University of the Philippines in the city of Los Baños, an area also known for its hot springs resorts,” Redondo said. “That is where they wanted us to go. When I discovered that the university offered a degree in Food Science and Technology, I knew I had to pass the tough exams and get into the program.”

Part of Redondo’s university studies included collaborative work with Nestlé Philippines, Inc. The company was looking for ways to develop coffee and coffee mixes that aligned the most sensory appeal for Filipino consumers with its international standards. As a student and during an internship at Nestlé, Redondo helped develop “3-in-1” flavored coffee mixes that were launched commercially to Philippine consumers under the Nescafé brand.

Redondo noted that the University of the Philippines is the top university in the country and has generated countless breakthroughs in research and established trailblazing leadership in agriculture, veterinary medicine, and forestry education.

Future food technologists at their 2001 graduation from the University of the Philippines, Los Baños. College buddies (L-R) CJ, Redondo, Ed, and Joel were all student members of the Philippine Association of Food Technologies.

After graduation (which offered a great sense of pride for his grandparents), Redondo took the advice of his Nestlé internship supervisor to gain a wide range of experience inside the Philippines’ thriving food production industry before venturing outside as a sales representative. So, he said the start of his career included “most of the work that a food technologist could see,” including research and development, quality control and assurance, technical service, production management, and technical sales.

“Almost all of that work related to the baking industry,” Redondo said. “I did technical servicing for Sonlie International, a company that distributed LeSaffre yeast in the Philippines, and learned proper commercial baking there under the tutelage of the company’s Head Baking Technician Rolly Dorado, who had served as a baking consultant for U.S. Wheat Associates in the 1980s.”

Redondo also worked as a production supervisor for the food service department of “a local burger chain” and in research and development for a company supplying premixes to Dunkin Donuts franchises in the Philippines.

Toward the Next Generation

His next career move into technical sales for commercial ingredient companies put him on a direct path to his current position in USW’s next generation of technical experts.

“I love to meet people, interact with them, and share what I know while learning from them at the same time,” Redondo said. “I had that opportunity as a technical sales executive at Bakels, a Swiss company that manufactures, sells, and supports high-quality bakery ingredients around the world.”

Redondo joined Bakels Philippines in 2005, where he found great value in the work of a colleague, Gerardo Mendoza, who is now a veteran Baking Technologist with USW/Manila.

Redondo worked with USW Baking Technologist Gerry Mendoza (left) when they both worked in technical sales at a global bakery ingredient company, Bakels.

“I worked with Gerry on provincial accounts, and eventually, I moved to key accounts where I had a lot of success,” Redondo said. “Gerry moved on, and I moved on to a multinational food ingredient company called Ingredion, specializing in modified starches and sweeteners.”

Redondo said his experience at Nestlé opened the door to the technical sales position at Ingredion. Gleaning from Mendoza’s passion for the work and people and his experience at Bakels, Redondo was able to build additional revenue for Ingredion’s Philippines and greater Southeast Asia bakery segment. He was recognized with Southeast Asia Top Sales Awards and “Best Campaigns” for three consecutive years.

“I think this success also came from trying to create additional value for whatever product Ingredion was selling,” Redondo said.

Any Resource Available

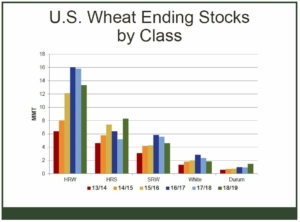

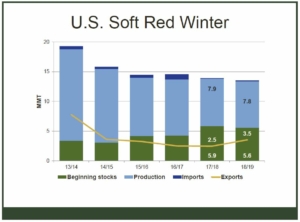

Toward the end of the ten years Redondo spent at Ingredion, USW Regional Vice President Joe Sowers was making plans to maintain a high level of technical support to the growing wheat foods industry in the Philippines. USW/Manila’s reputation for employing any resource available to help its customers succeed has helped make the Philippines the top global market for U.S. hard red spring (HRS) and soft white (SW) wheat. A fortunate change in USW’s funding sources helped solidify Sowers’ plan.

“As a result of the trade dispute between the United States and China, USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service made additional export market development funding available under the Agricultural Trade Promotion (ATP) program,” Sowers said. “This allowed us to hire a new Technical Specialist in Manila who could expand our after-sales service while training for a long time with our regional technicians. Fortunately, Gerry Mendoza had someone in mind for the job.”

“I liked working in the commercial food industry, but no matter how well you did, you would only be as good as last month’s or last year’s sales,” Redondo said. “Then, I was able to talk with Gerry and Bakery Consultant Roy Chung during an interview, who told me that success in technical support at U.S. Wheat Associates would be about helping local companies grow while helping farmers in the United States build demand for their wheat. I was all in after that talk.”

“We knew Ady had a solid background in the bakery ingredients industry that gave him the capability and credibility to contribute at a high level to our mission in the Philippines from his first day,” Sowers said. “He has also shown a strong work ethic combined with a pleasant demeanor since he joined our team in June 2019.”

“Right away, I understood that my focus would be on building relationships and serving bakery manufacturers and associations, providing technical support to flour mills, and promoting innovations in baking and quality analysis in the Philippines,” Redondo said.

Character Doesn’t Change

Late on a Friday afternoon, not long after he joined USW, Redondo had the chance to apply that focus to a flour mill that had a question about performance issues with a new U.S. wheat crop shipment. Sowers said Redondo responded immediately and asked to visit the mill Saturday morning to understand the problem better. Coordinating with other USW colleagues and a state-side university expert, Redondo was able to help the customer solve their immediate concerns and change purchase specifications to avoid similar issues in the future.

“Roy Chung likes to say the value of people is in their character; skills can be learned, character doesn’t change,” Sowers said. “Redondo’s willingness to go the extra mile, providing attention outside of office hours, was a solid indication that he would be very successful with our organization.”

That is becoming a hallmark of Redondo’s work. A Philippines baking industry executive recently noted that he is easy to work with and always responsive to the company’s inquiries.

“I am thankful that during this COVID-19 pandemic, Redondo was able to respond to our request for a webinar about Solvent Retention Capacity (SRC) as a measure of flour functionality,” the executive said. “He effectively organized the webinar and gave us new knowledge, proving there is no right time and venue to learn. He is surely adding value to U.S. wheat.”

In addition to “learning the ropes” with Mendoza and Chung, Redondo said he had been actively participating in trade visits, technical support inquiries, and teaching bakery science until the pandemic put restrictions on face-to-face customer interaction.

In October 2019, Redondo (back row, fourth from right) helped Mendoza (seated first on the left), USW Seoul Country Director CY Kang (front row seated, third from left), and USW Seoul Food/Bakery Technologist Shin Hak (David) Oh (front row sitting on the far right) organize and conduct two Baking Workshops on Korean Breads and Cakes to help Philippine bakers diversify product offerings as well as production techniques.

Another opportunity Redondo looks forward to is a Cereal Science Seminar he and Mendoza have created for technical staff at local flour mills.

“This will hopefully give them a better understanding of the quality testing they conduct with wheat and flour,” Redondo said. “And, of course, to help further affirm the superior qualities of U.S. wheat.”

While continuing to help customers and train with his USW colleagues, Redondo looks forward to the future.

“I like the working culture at U.S. Wheat Associates,” he said. “Everyone is so passionate about their jobs. They genuinely work as if they are fulfilling a duty of care for their industry, which is infectious. This really is an organization you can grow in – and it also grows on you.”

By Steve Mercer, USW Vice President of Communications

Editor’s Note: This is the eighth in a series of posts profiling U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) technical experts in flour milling and wheat foods production. USW Vice President of Global Technical Services Mark Fowler says technical support to overseas customers is an essential part of export market development for U.S. wheat. “Technical support adds differential value to the reliable supply of U.S. wheat,” Fowler says. “Our customers must constantly improve their products in an increasingly competitive environment. We can help them compete by demonstrating the advantages of using the right U.S. wheat class or blend of classes to produce the wide variety of wheat-based foods the world’s consumers demand.”

Meet the other USW Technical Experts in this blog series:

Ting Liu – Opening Doors in a Naturally Winning Way

Shin Hak “David” Oh – Expertise Fermented in Korean Food Culture

Tarik Gahi – ‘For a Piece of Bread, Son’

Gerry Mendoza – Born to Teach and Share His Love for Baking

Marcelo Mitre – A Love of Food and Technology that Bakes in Value and Loyalty

Peter Lloyd – International Man of Milling

Ivan Goh – An Energetic Individual Born to the Food Industry

Adrian Redondo – Inspired to Help by Hard Work and a Hero

Andrés Saturno – A Family Legacy of Milling Innovation

Wei-lin Chou – Finding Harmony in the Wheat Industry