By Tanner Ehmke, Manager, Knowledge Exchange, CoBank; Reprinted with permission;

View the original report here.

Key Points:

- Blockchain innovations in agriculture are numerous but have been slow to gain industry-wide acceptance, particularly in global agriculture commodity trading.

- Previous attempts to digitize trade finance with tools like bank payment obligation (BPO) have been slow to take hold, raising doubts among market participants of new digitalization efforts like blockchain.

- Commodity agricultural trade faces unique challenges, including the blending of grain along the supply route, and the lack of digital documentation within sections of the supply chain.

- Digital solutions are quickly evolving, creating an environment where blockchain technologies may be more viable in ag commodity trading in the near future.

- Investment in storage, transportation, and sensors to segregate and track commodities through the supply chain is necessary to give buyers visibility, with high-value or value-added commodities like non-GMO and organic grain where provenance and tracking are desired.

Introduction

Blockchain, the distributed ledger technology behind cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin where identical records of transactions are stored on multiple computers, is still in its infancy but has seen a flood of pilot programs and proof-of-concepts from companies around the world as they race to harness its power of transparency. The agriculture and finance industries in particular have captured the spotlight as ripe for disruption by blockchain technologies. Adoption of most blockchain technologies across agriculture, however, has been limited to date. Banks and agribusinesses nonetheless remain keen on finding distributed ledger solutions to deploy industry-wide and potentially achieve efficiencies from faster transaction speeds, less cumbersome documentation, and simpler and faster payments between buyers and sellers around the world.

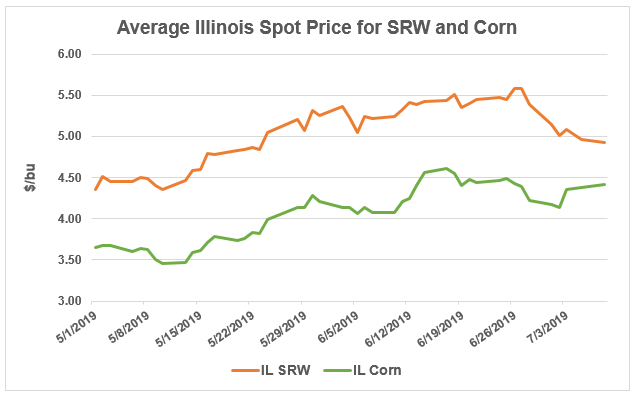

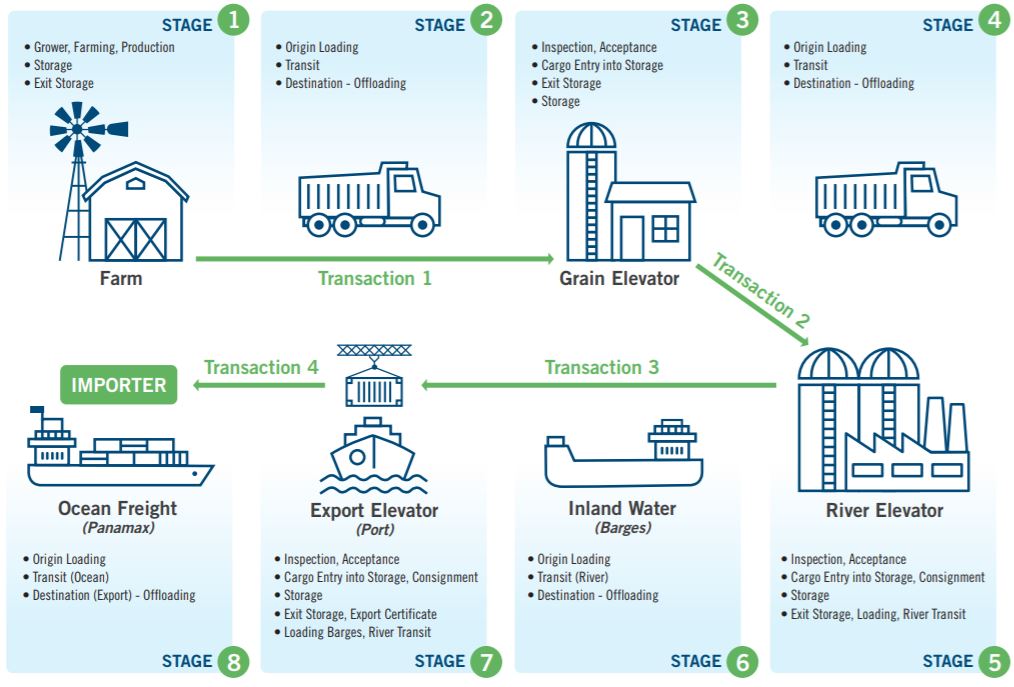

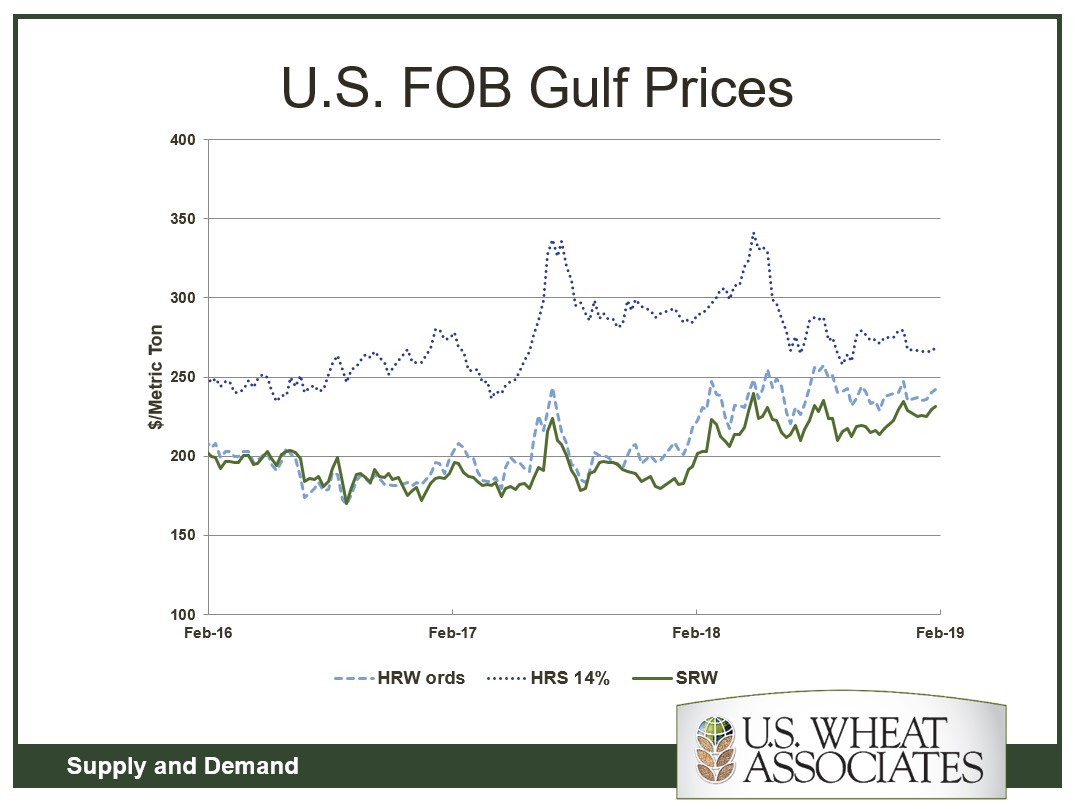

EXHIBIT 1: Process of Domestic Supply Chain for U.S. Soybean Export via Barge; Graphic Source: CoBank

Other digital solutions that promised to transform the commodity trading sector, such as bank payment obligation (BPO), are recent reminders that change can be hard work without industry-wide acceptance. Until numerous roadblocks to blockchain solutions are resolved, such as a lack of a digital ecosystem for paperwork like bills of lading and letters of credit for parts of the supply chain; improvement in global industry protocols in quality; standards in language; investment in storage and transportation for segregation; and technological advancements in sensors to monitor movement of commodities along complex trade routes, industry-wide adoption of blockchain in agricultural commodity trading will struggle to grow beyond proof of-concept. But, if successful, blockchain could be transformative across the sector, bringing value across the supply chain from producers to consumers.

Complex Supply Chains

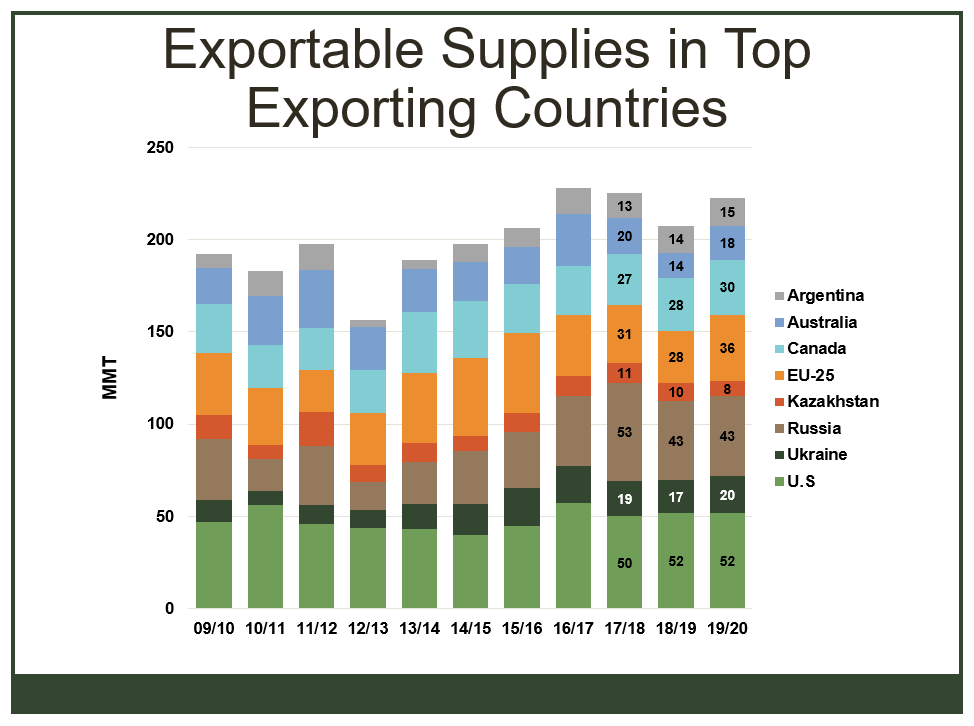

Blockchain applications for agriculture abound. Ripe.io, GrainChain, AgriDigital, OriginTrail, and IBM Food Trust are just a few of the blockchain-based technologies created for commerce in agriculture. Yet in the complex global agricultural commodity space where crops like corn, soybeans, and wheat are blended from numerous farms and pass through multiple hands before reaching the final destination, a blockchain solution that links the supply chain and creates transparency of transactions from beginning to end remains in idea phase. The biggest challenge for the widespread adoption of blockchain technologies in agricultural commodity trading is the complexity within the chain of custody (Exhibit 1). Grain leaving the farm is often comingled at a country elevator, then blended again at a rail or barge loading facility, then comingled again at the export facility where it is loaded on an ocean vessel for export. At the receiving port overseas, grain will likely be blended even more after off-loading the vessel.

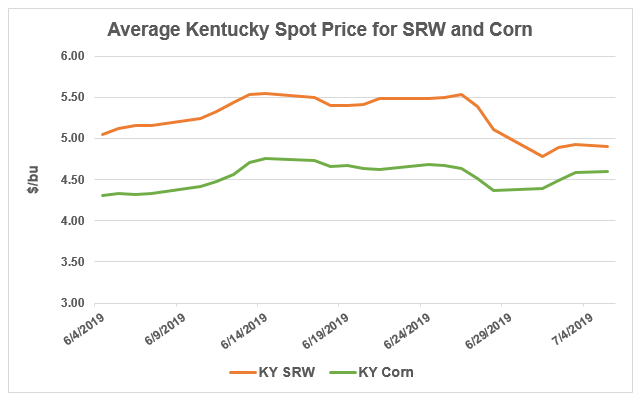

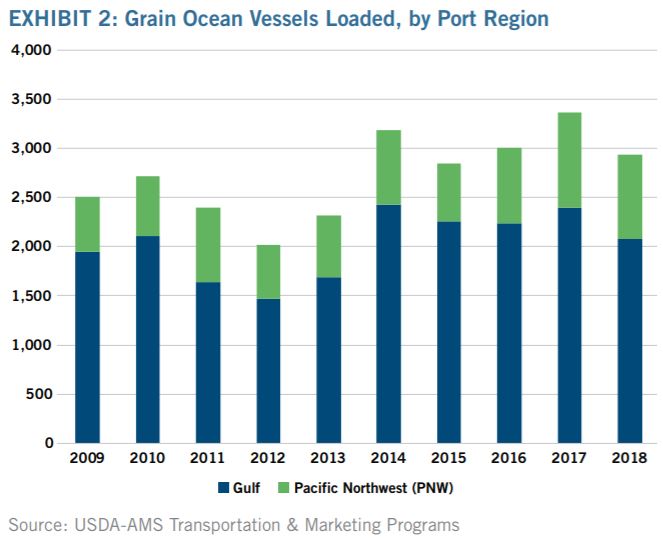

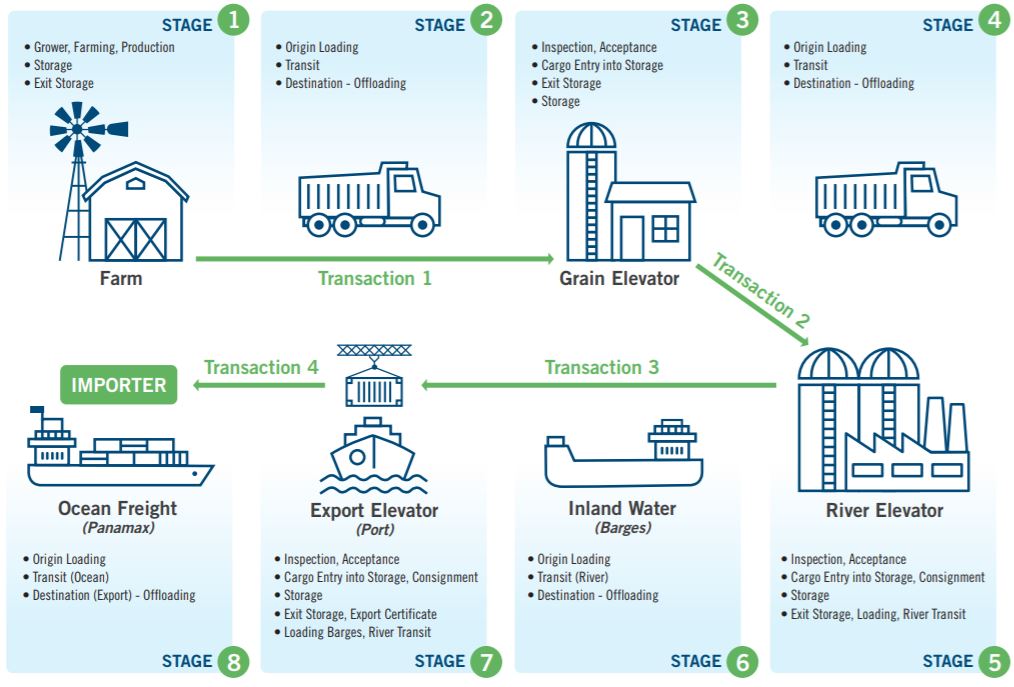

EXHIBIT 2: Grain Ocean Vessels Loaded, by Port Region; Graphic Source: CoBank

Digitizing even portions of the supply chain could create huge cost savings for grain handlers. The physical delivery of documents like bills of lading, letters of credit, contracts, letters of intent, and invoices is cumbersome. While costs of shipping documents are negligible and could be eliminated with a blockchain platform, the cost and risk of important documentation arriving late could be far greater. If documents to the receiver of the grain do not arrive on time, the shipper must pay the cost of demurrage for every day the barge, rail car, or vessel sits idle. Cost of demurrage per barge, for instance, can run about $300/day. Demurrage is a charge for failure to load or unload barges, rail cars, or ocean vessels within the time allowed.

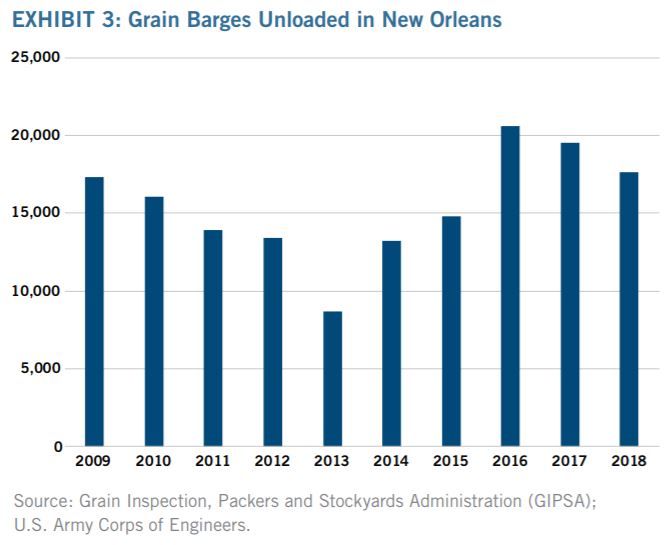

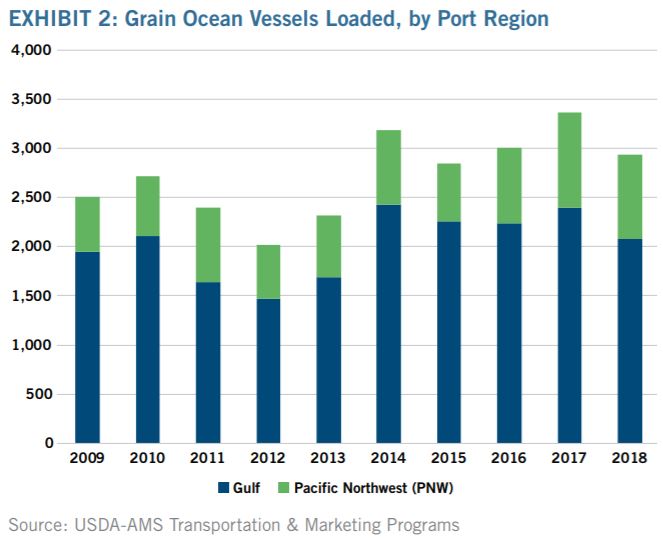

A non-blockchain based digital solution currently is being evaluated by a consortium of agribusinesses for barge freight on the Mississippi River for the purpose of reducing paperwork and creating seamlessness in transactions between companies. Paperwork such as bills of lading and letters of credit have digital forms for ocean vessels, but are in paper form for barge traffic on the Mississippi River, which is an important logistical leg of the global agricultural commodity supply chain. Digitizing paperwork on the Mississippi River export route offers the greatest potential for blockchain solutions in global agricultural commodity trading. The majority of U.S. ocean-going vessels loaded with grain depart from the New Orleans region (Exhibit 2).Barge traffic for grain on the Mississippi River regularly exceeds 15,000 barges/year (Exhibit 3). The plethora of documents in the grain trade that must be digitized for seamlessness across the supply chain includes but is not limited to:

- Letters of credit

- Bills of lading

- Trading slips

- Certificates on weights, grades, phytosanitary

specifications, fumigation, and origin.

Additionally, the industry would need agreement on where in the supply chain the data would be committed to the blockchain, such as at the barge or rail car loading facility, or at the farmer’s field. The data on a blockchain for grain traded on the inland river system would then also have to be integrated with systems for ocean-going vessels heading to international markets, thereby requiring international standards for data and governance.

EXHIBIT 3: Grain Barges Unloaded in New Orleans; Graphic Source: CoBank

Disillusionment

Previous attempts to digitalize trade finance were heralded as transformative but have yet to change the status quo in global trade. In recent years, the bank payment obligation (BPO) was created with significant investment and promised faster handling of goods, payment at due date, and faster receipt of trade documents. The lack of wide-spread adoption of BPO has raised doubts among market participants of new digitalization efforts like blockchain. A blockchain platform may not be adopted industry-wide despite significant investment and coordination, particularly in emerging markets where there is frequently a lack of consistency in technology. Or, if successfully adopted, a blockchain platform could itself be disrupted by yet another new technology. Questions about ownership of data on a distributed ledger have also raised concerns. Trading firms want information to be private. If chain of custody information is visible for anyone on the supply chain to see on a distributed ledger where each market participant or node would have access to all documentation, merchandisers will be reluctant to use

a blockchain platform. Who will gain access as a node in the blockchain will require governance and rules, thereby requiring a governing body trusted by all parties of the supply chain to host nodes and validate transactions. Blockchain would not reduce or eliminate the need for regulators. Maintaining the quality of information that is inputted into the blockchain would require a licensed inspector who might need access to the blockchain to see documents and integrate their certification information on grading. A regulator or third party would also still be needed to define responsibilities, rules, and regulations of supply chain participants despite blockchain widely thought of as a technology that would replace trusted intermediaries. With the huge volume of shipments moving outside of the U.S., cooperation from international buyers is required to create the protocols necessary for blockchain in agricultural commodity trading to flourish. However, the current geo-political climate – especially with the U.S. and important trading partners like China – raises doubts about achieving a globalized trading system on a blockchain.

Blockchain’s application in the ag commodity trade may also be limited to only portions of the supply chain. If farmers and country elevators are not incentivized either through cost savings or gain in value, adoption of blockchain will be limited to segments further down the supply chain.

Evolution

Despite major challenges impeding blockchain’s use in the global grain trade, the potential opportunities achieved through a distributed ledger system could be significant. Blockchain could potentially expedite borderless clearing, help facilitate digitally validated chains of custody through choke points like barge and train loading facilities, allow buyers and sellers to follow a shipment through various chains of custody, lower the cost for clearance of goods, eliminate duplicated inspections at ports, lower risk of demurrage, assist with payment, mitigate counter-party risk, and greatly reduce the risk of errors and fraud. Corn, which has the simplest trade specifications under the Federal Grain Inspections Service (FGIS) would be the easiest commodity to adopt into a distributed ledger platform, followed by soybeans and wheat. If provenance is important, sharing knowledge of the entire chain of custody will be necessary for commodities like non-GMO and certified organic. Through investment in grain storage and transportation for segregation, greater transparency in the supply chain to segregate other attributes, including but not limited to:

a. High-oleic oil content for soybeans

b. Protein content

c. Foreign matter

d. Moisture levels

Further investment in electronic sensors to trace, validate, and verify quality attributes, though, would be required to make transparency possible along the complex commodity trading route. With sensors in place, a blockchain platform could evolve to include payment systems within “smart contracts” that automatically execute transactions without human intervention as the product moves through the supply chain. However, a distributed ledger system that shares this information would also need to protect proprietary information held only between buyers and sellers.

Conclusion

The challenges of industry-wide adoption of blockchain technologies for agricultural commodity trading are ample, but so are the potential benefits. Greater visibility in the supply chain will create value for many, but standards will change. The winners in a hypertransparent environment will be those who have the ability to segregate and capture higher value in the commodity chain. Those who struggle to adapt will be those with limited ability to segregate. Experiences with prior efforts to digitize trade have raised the level of caution for blockchain. High investment into blockchain may not result in industry-wide adoption. If successfully adopted, a blockchain platform could crowd out small players. It could also be disrupted by yet another new technology.

To be successful, a blockchain platform bringing transparency to an entire supply chain would need to be private and secure from outside parties. Only invited parties or nodes would be allowed to view the data on transactions for traders to be confident that proprietary information is not made public. This would require a governing body to determine who is allowed to participate on the blockchain.

Global standards and protocols will also need to be established. Given the current geo-political and global trade environments, such an evolution in international cooperation will likely be years in the making.