By Stephanie Bryant-Erdmann, USW Market Analyst

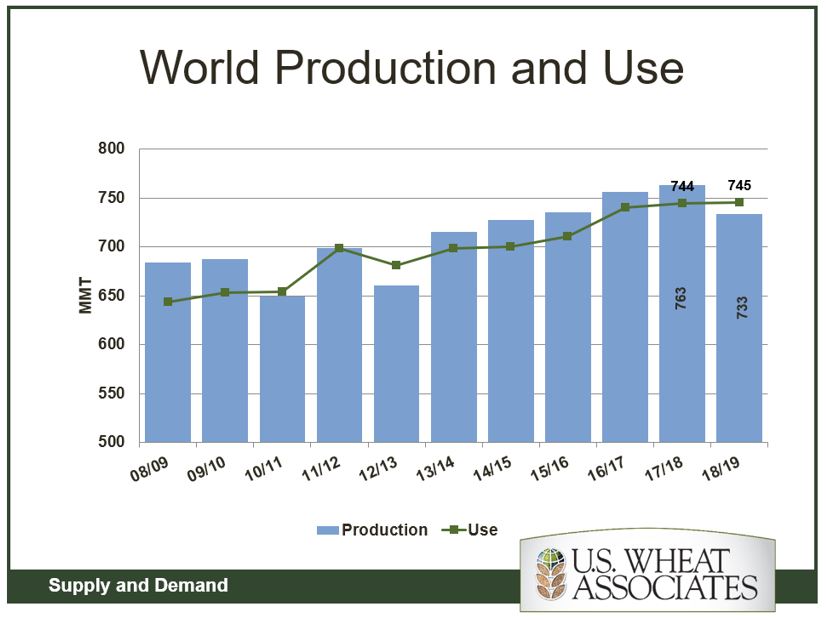

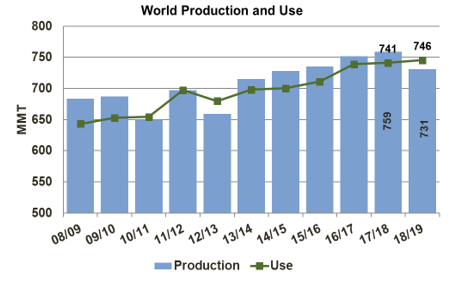

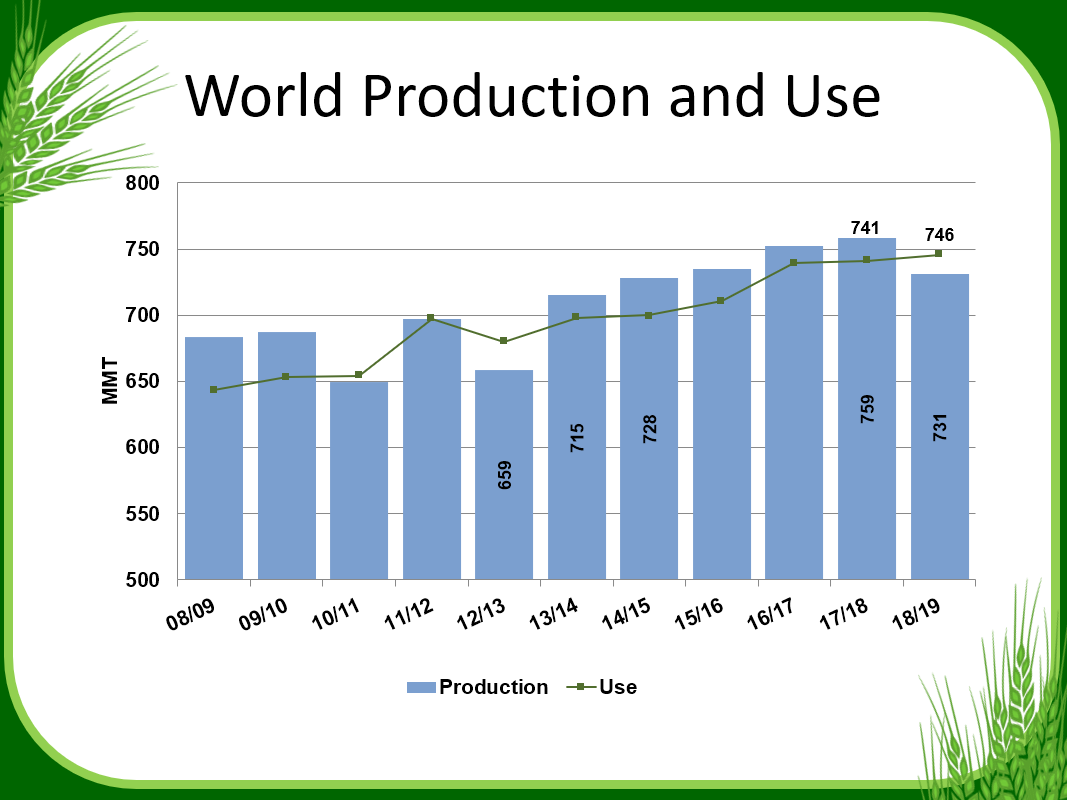

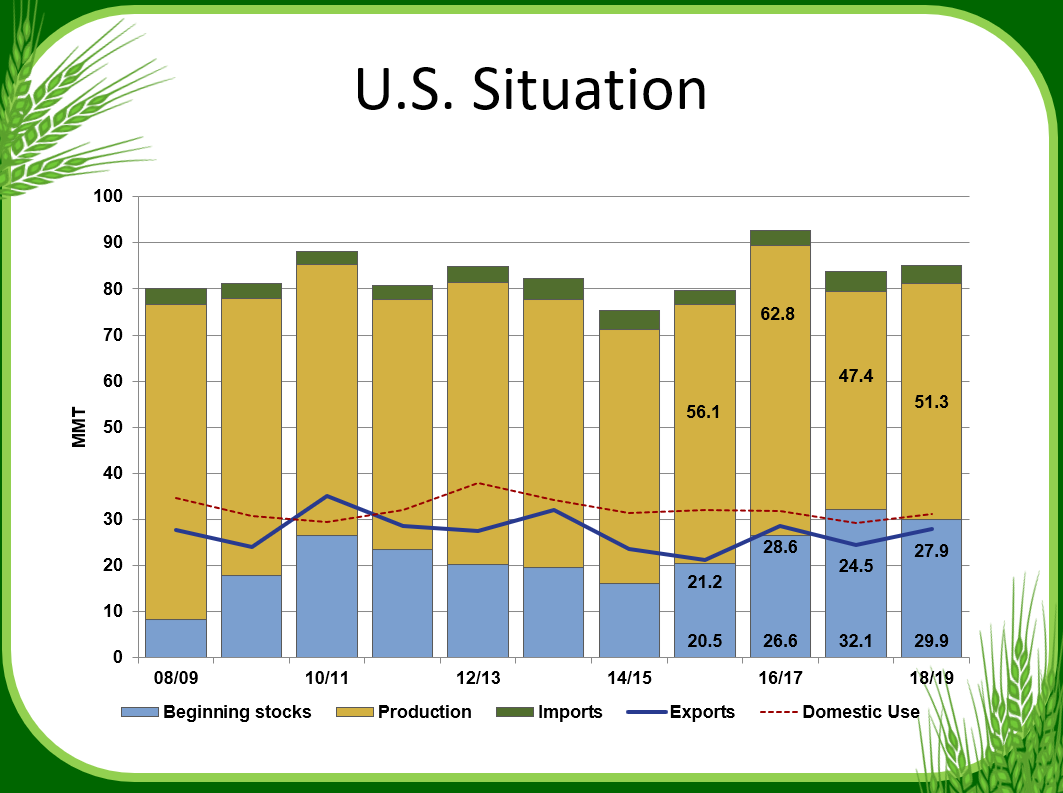

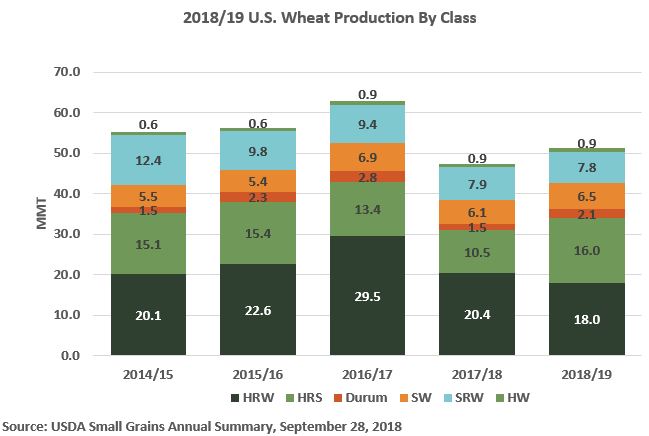

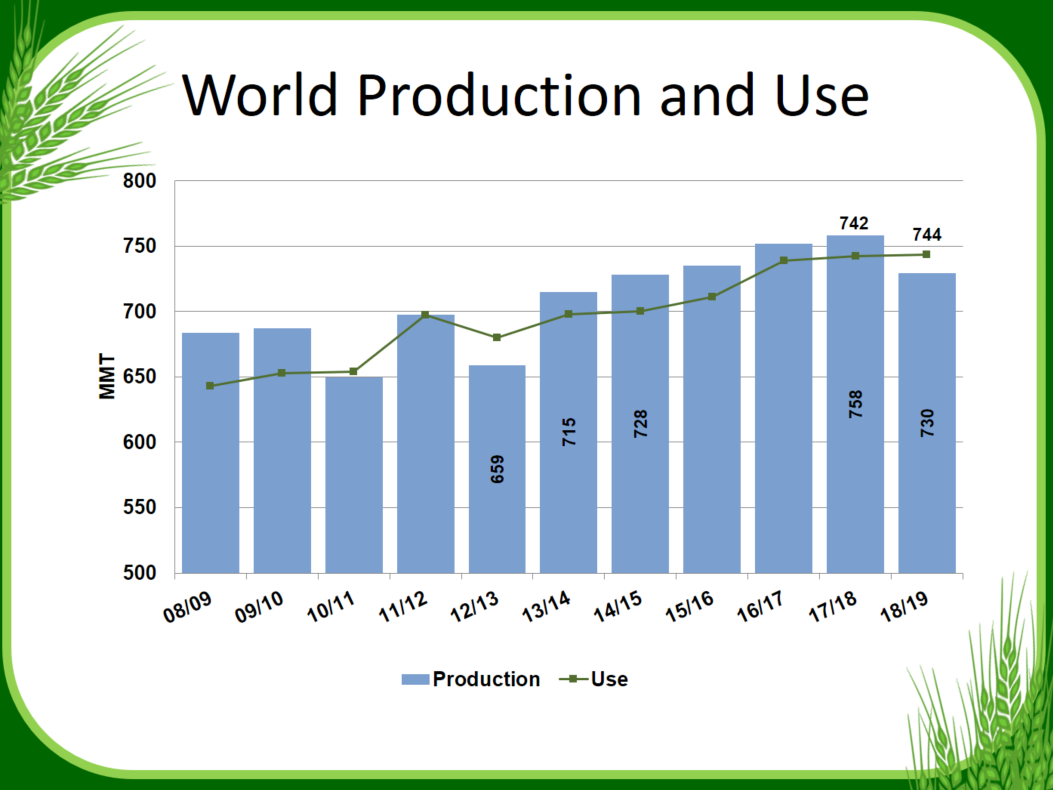

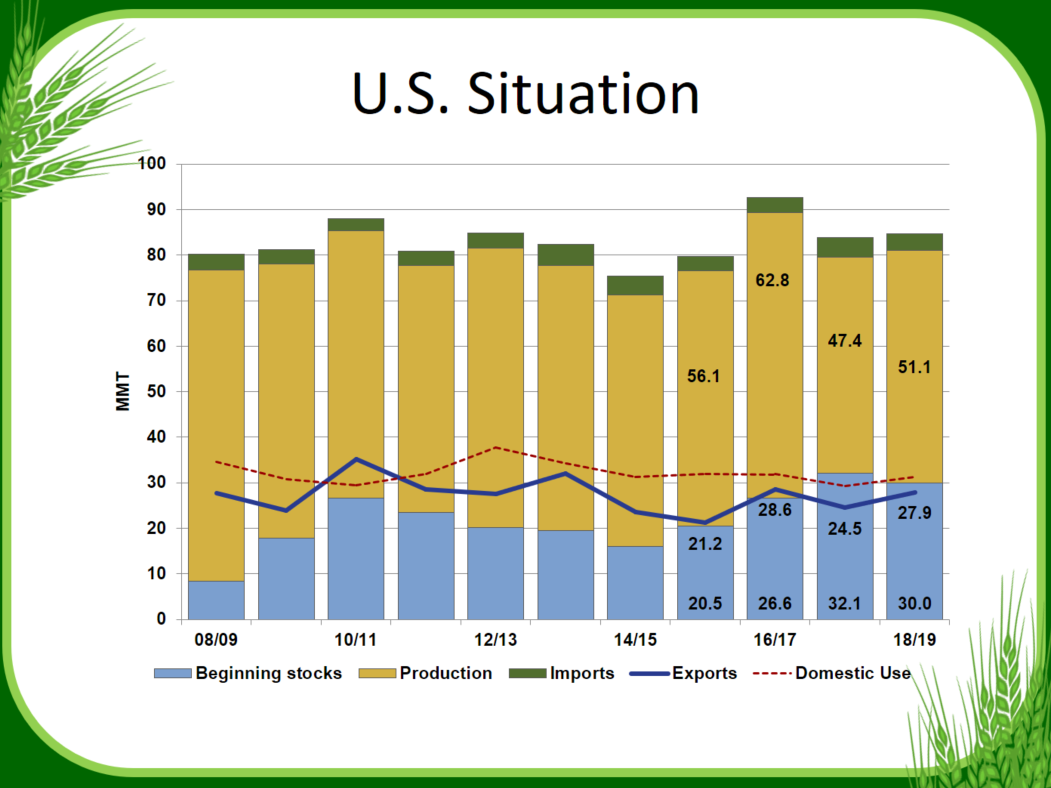

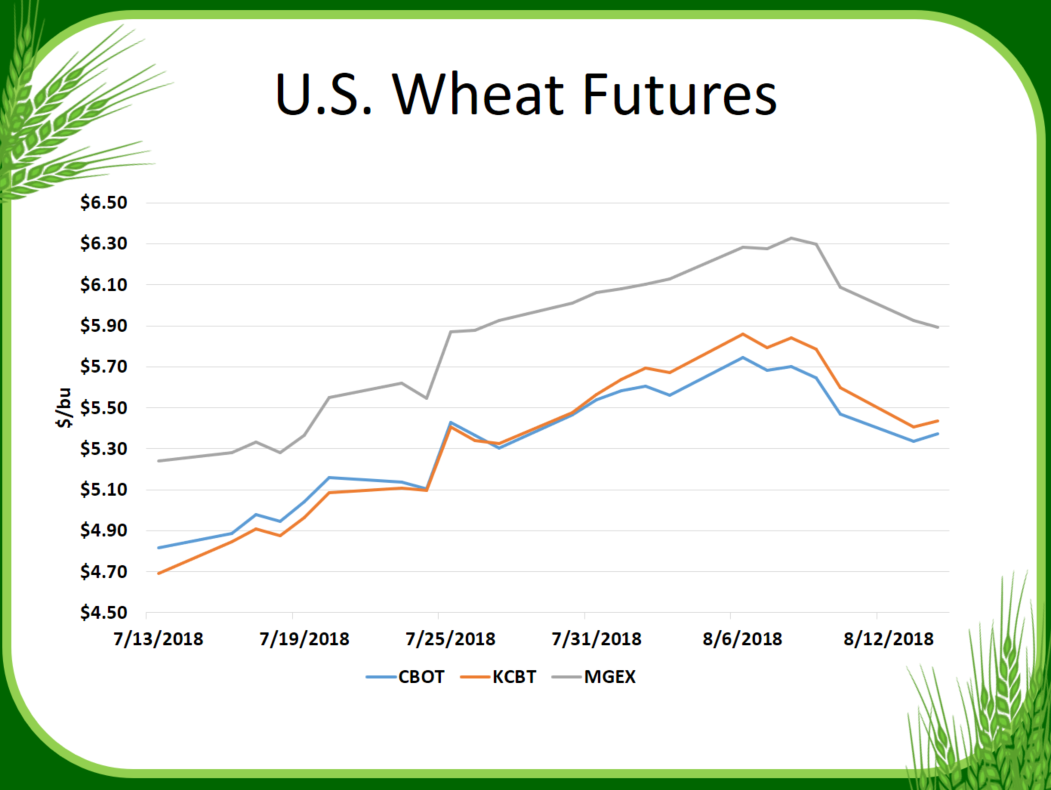

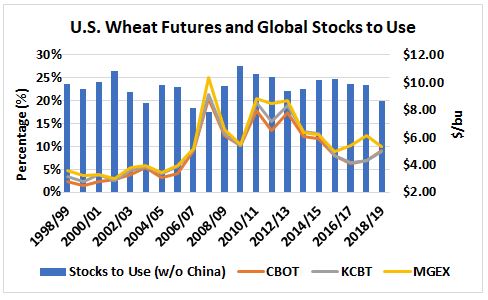

On Aug. 10, USDA increased its U.S. wheat export forecast to 27.9 million metric tons (MMT), up 14 percent from 2017/18, if realized. With 2018/19 global wheat production falling to 730 MMT, down 4 percent year over year, and supply in exporting countries shrinking to the lowest level in four years, USDA seems to anticipate global demand turning to U.S. wheat supply. That raises two questions:

- Is there that much demand for U.S. wheat out there?

- Can the U.S. grain transportation system handle the increase in wheat exports?

Is there that much demand for U.S. wheat out there?

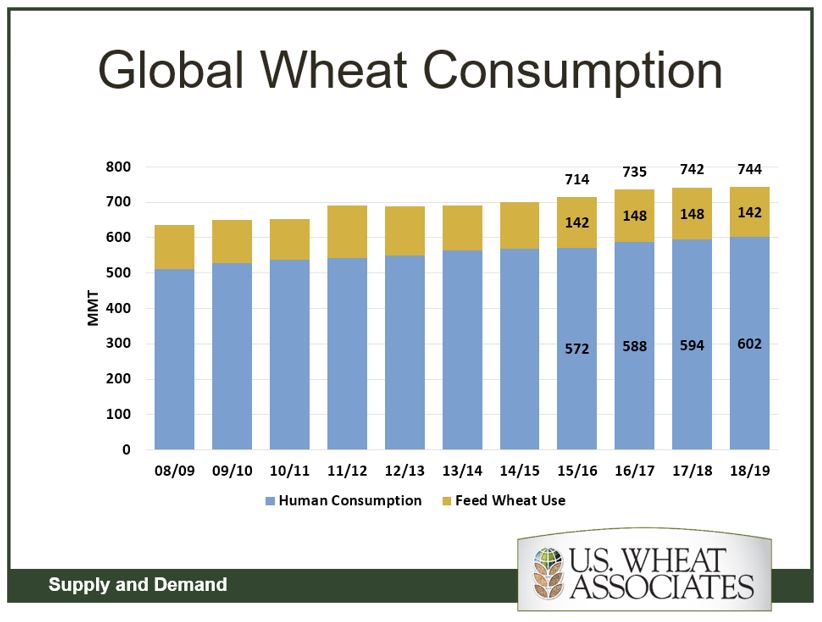

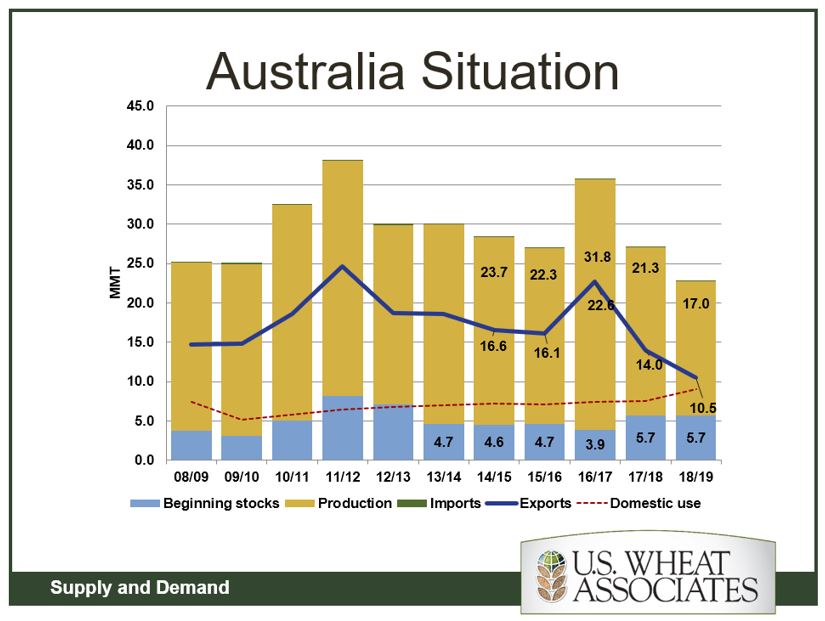

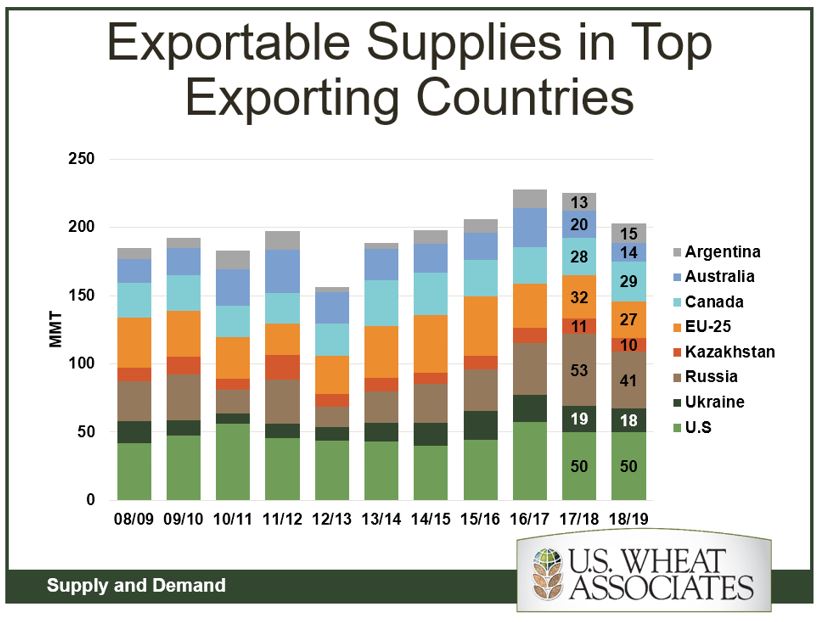

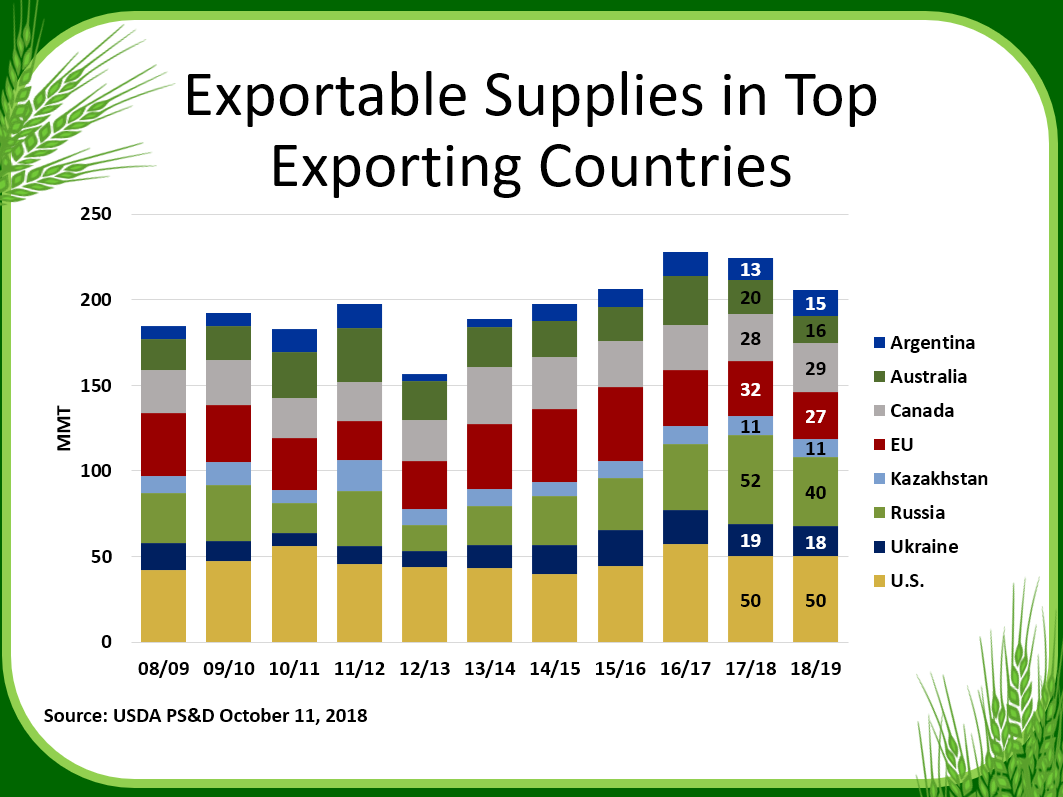

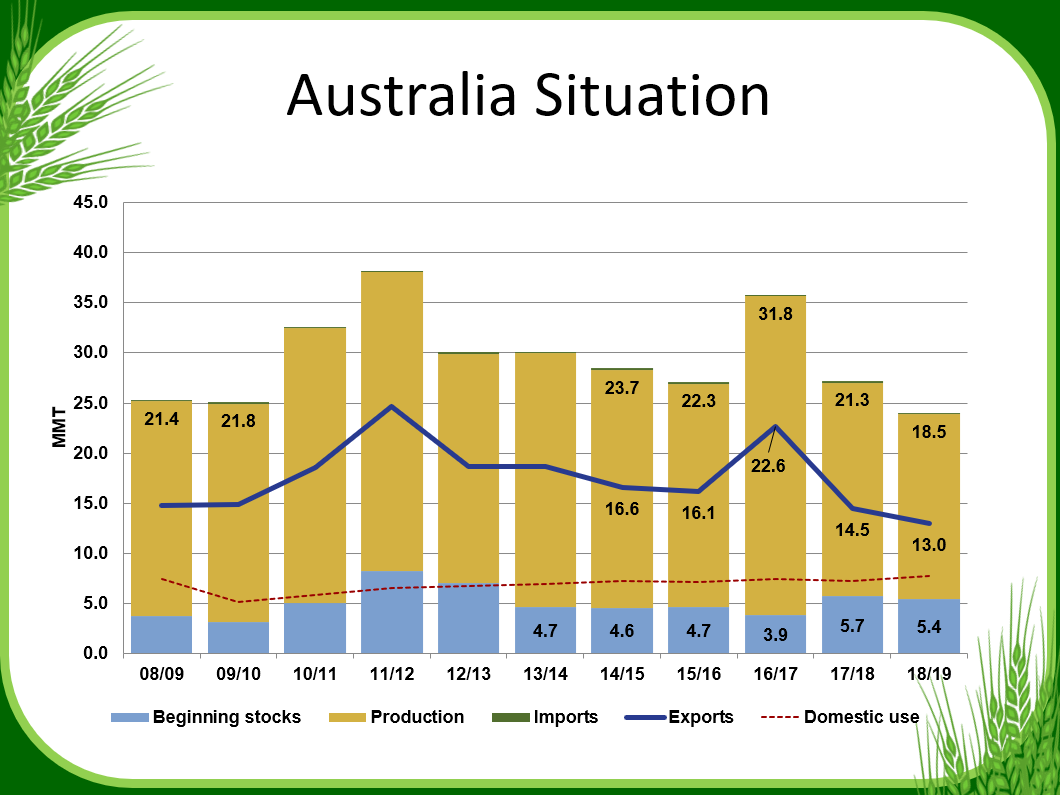

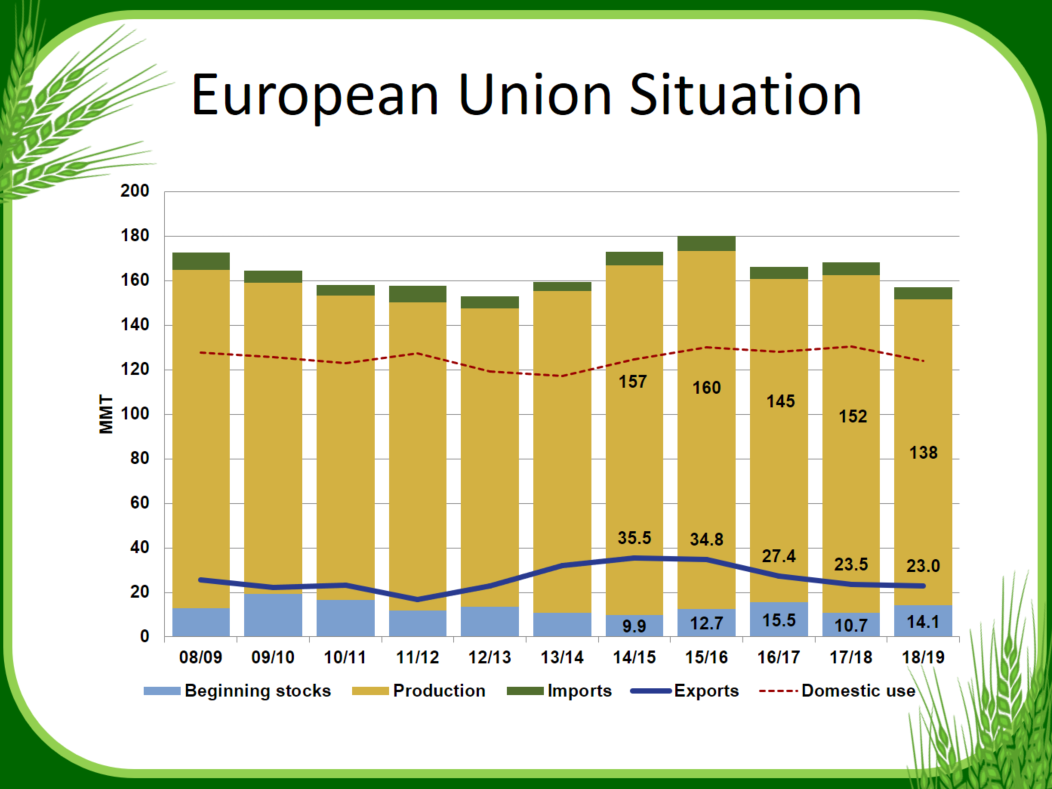

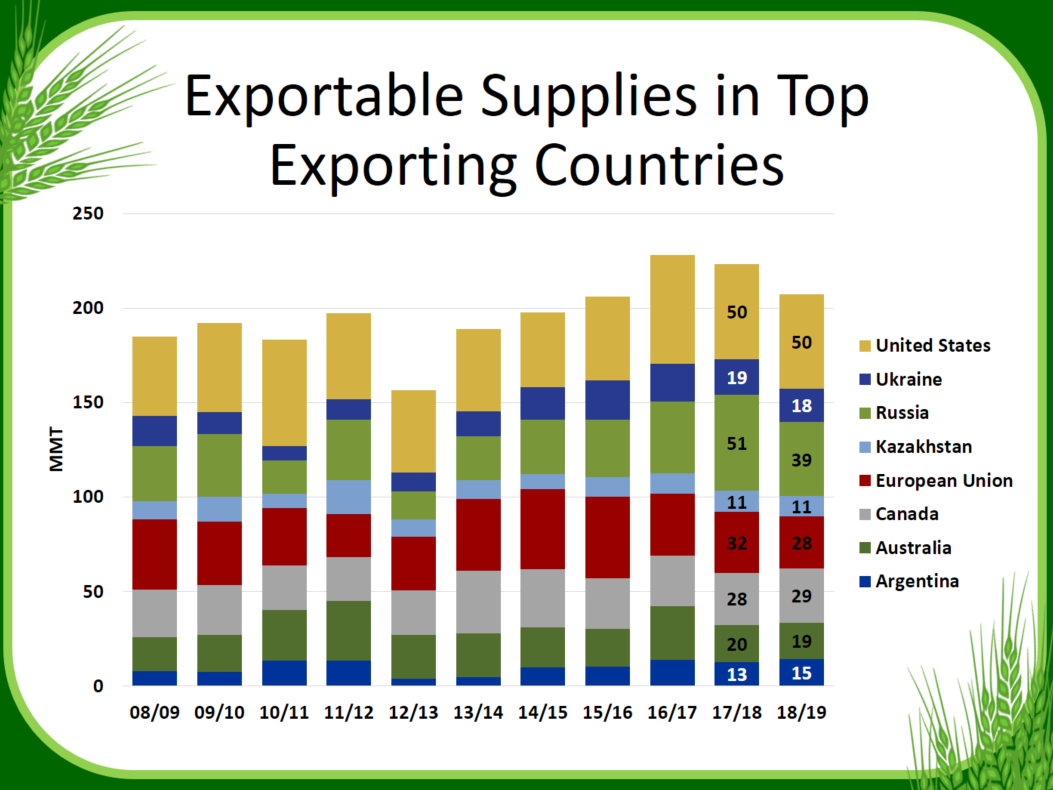

Based on USDA estimates, global wheat trade will need to increase to a new record high of 184 MMT in 2018/19 to meet global wheat consumption. With Russia and the European Union (EU) wheat exports expected to decline by a combined 7.5 MMT in 2018/19, and the extreme drought in Australia threatening its exportable supply, it is logical that U.S. wheat supplies will fill a crucial role in global wheat consumption.

Still, the United States will need to record an additional 19.6 MMT of export sales in the remaining 42 weeks of the 2018/19 marketing year, which began on June 1, or an increase in weekly sales from an average of 409,300 MT to 466,000 MT. Put another way, the United States needs to sell about two more vessels of wheat per week to reach the USDA estimate.

However, nearly two-thirds of that increase could come from just the top 20 U.S. customers, excluding China, based on historic buying patterns. For example, the top five U.S. wheat customers — Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, Nigeria and Korea — imported an average of 11.4 MMT of U.S. wheat exports the past five years. U.S. export sales to many top customers are behind last year’s pace, traders report continued interest in U.S. wheat and note that many customers are engaging in “just-in-time” buying patterns that result in large, last minute shipments that are challenging logistically. And that leads to the question:

Can the U.S. grain transportation system handle the increase in wheat exports?

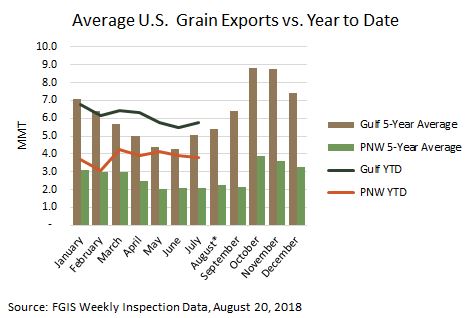

The short answer is, “it depends.” The slightly longer answer is, “it depends on weather and trade policies.” Both of which are relative unknowns at this point. One thing is certain. Winter is coming and will bring, as it always does to some extent, cold weather and snow across the U.S. Northern Plains and Pacific Northwest (PNW) and ice and fog on the Mississippi River system, along with associated commodity movement delays.

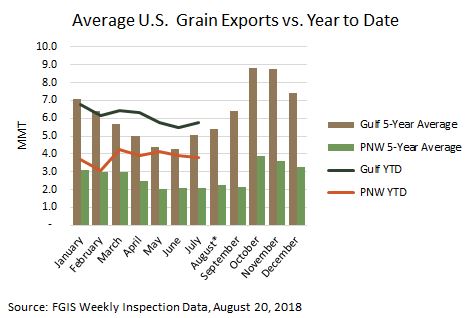

During the winter months of December, January and February, U.S. Gulf all grain exports — including corn, sorghum, soybeans and wheat — average 6.67 MMT per month, down 24 percent from the peak month of October when 8.81 MMT of grain typically moves through the ports. For comparison, PNW all grain winter month exports average 3.13 MMT per month. This is an average 19 percent below the PNW peak export month of October when all grain PNW exports average 3.86 MMT.

Trade policies will determine how much competition U.S. wheat exports face for freight and export elevation. U.S. Gulf grain exports center around four main commodities — corn, sorghum, soybeans and wheat, while U.S. PNW grain exports typically include barley, canola, corn, flaxseed, sorghum, soybeans and wheat. In the Gulf, soybeans account for roughly two-thirds of total grain shipments during the peak fall months of October and November. In the PNW, it is closer to 75 percent.

USDA’s August estimate is based on the current, enacted trade policies. As such, USDA expects U.S. feed grain and soybean exports to decrease by a combined 3.53 MMT year over year due primarily to decreased demand from China. In theory, reduced U.S. feed grains and soybean exports should increase freight and export elevation availability for wheat. However, through Aug. 16, there are already 8.86 MMT of U.S. corn export sales booked for the 2018/19 marketing year (beginning Sept. 1). That is up 54 percent from last year and 12 percent above the 5-year average. U.S. soybean export sales for the new marketing year (beginning Sept. 1) are also up 45 percent year over year at 11.5 MMT. That increased drain on export capacity and the tightening global feed grain supply situation, as discussed in Ahead of USDA Report, Wheat Futures on a Powder Keg, indicate there may be upside potential for USDA’s estimates even with the existing uncertainty around U.S. trade policies. Customers should carefully watch the corn, soybean and feed grain supply and demand situation as it will impact freight and export elevation demand. While the expectation is that U.S. soybean and corn exports will be down, right now the data suggests otherwise.

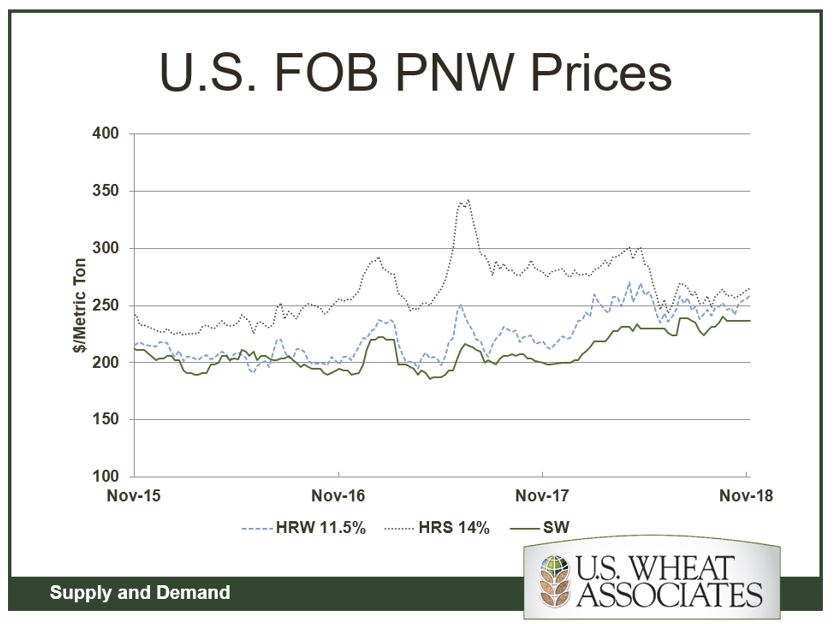

With increased global demand for U.S. wheat likely and an uncertain outlook for U.S. transportation logistics, customers should take a serious look at the benefits of securing U.S. wheat supplies now. As always, the U.S. wheat store is open and ready to supply high-quality wheat — there just may be longer lines at checkout this year.