Instead of asking “what’s in store” for crackers and cookies and other wheat-based snack foods in a post-COVID world, those in the U.S. wheat industry may want to ask the same question in a slightly modified way.

What’s in the store?

When COVID hit in 2020, international consumers had already been drawn to convenient foods that fit snacking lifestyles. Boxes of crackers were tucked into office drawers. Sleeves of cookies – often referred to as “biscuits” in some foreign markets – were slid into backpacks. While work routines and travel screeched to a halt, snacking habits sped forward. In fact, market research over the past year has indicated that, in many countries, on-the-go snacking is now preferred over traditional sit-down meals, especially by younger consumers.

This movement was aptly labeled “Snackification.” It’s changing the look of grocery and supermarket shelves around the world.

It’s also creating potential opportunities for U.S. wheat.

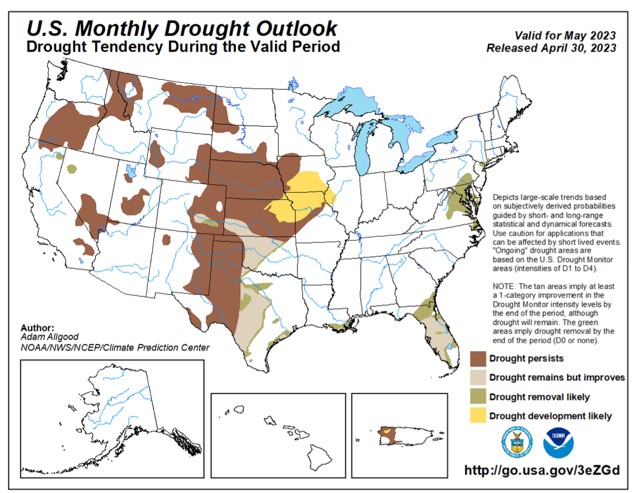

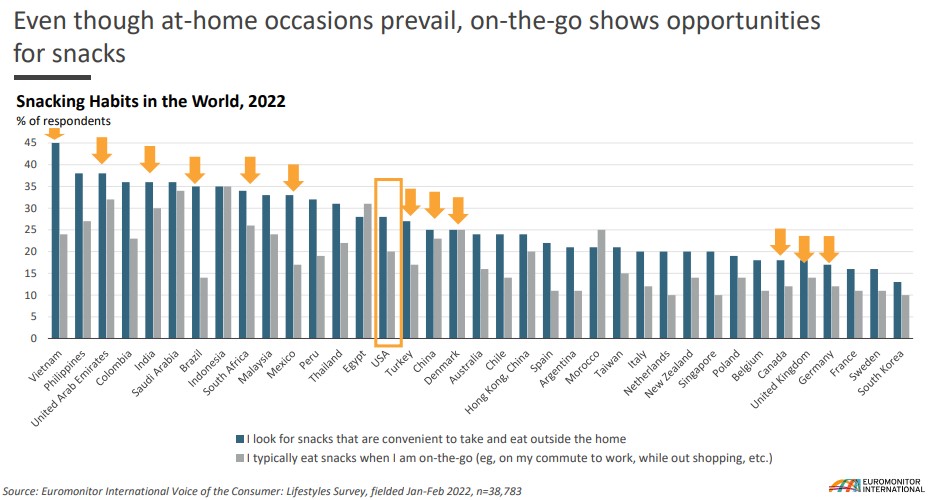

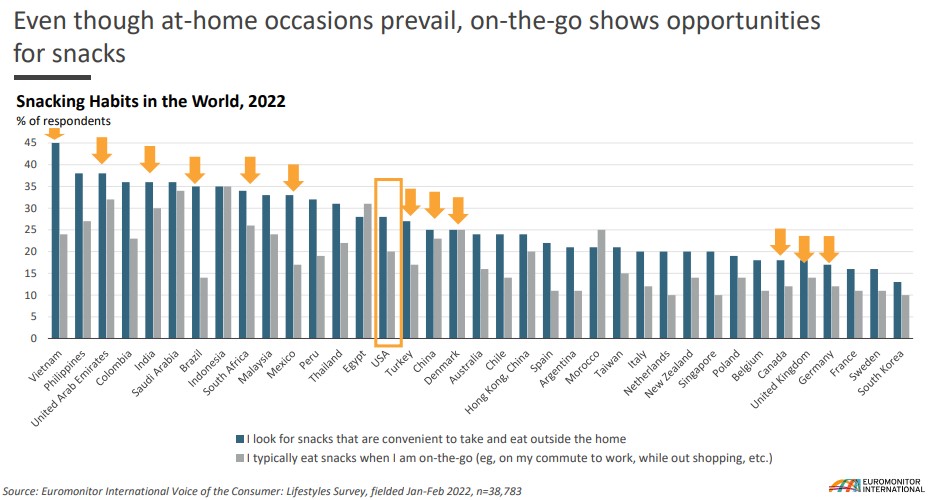

A 2022 survey by Euromonitor International revealed growing numbers of global consumers who look for snacks when shopping for food.

Snack ‘Em if You Got ‘Em

A Euromonitor survey conducted in 2022 showed South Asia as having the most robust snacking habits. About 45% of Vietnamese consumers surveyed indicated that when shopping for food, they “look for snacks that are convenient to take and eat outside the home.” Roughly 38% of consumers in the Philippines responded the same way. The survey revealed that in Latin America, Colombia had the highest number of outside-the-home snackers with 37%. Brazil was close behind at 36%.

As a comparison, and for perspective, fewer than 30% of consumers in the U.S. were focused on snacking while shopping for food.

Those who study global consumer trends expect the new generation of “snackificators” to munch its way into the future.

“Snack brands already had a large portion of the breakfast category – breakfast bars, breakfast cakes and pastries, and so on – but with consumer preferences changing during COVID, snack foods are now intentionally being positioned as meal replacements throughout the entire day,” offered Carl Quash, head of Snacks and Nutrition for Euromonitor International, an independent market research firm based in London.

Quash, who oversees packaged snack research and analysis in more than 100 markets worldwide, presented a webinar titled “Snackification: The Future of Occasions” to USDA stakeholders on Jan. 30.

“Snacking is likely to increase as people become busier and more mobile, and as they feel more comfortable in traveling once pandemic fears fade for good,” said Quash. “Add to that the fact many consumers are now replacing meals with snacks – they snack throughout the day instead of sitting down for a meal.”

Market research has shown increased demand for snack foods, as the dining habits of global consumers continue to evolve. USW continues to work with millers and bakers around the world to help in the development of new snack food products made with U.S. wheat and the improvement of existing products.

An Opportunity Knocking?

U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) recognized the new shift, even before snackification became a buzzword. USW’s offices around the world have long been involved in helping develop new snack products made with U.S. wheat, while also helping improve and promote existing products in all markets.

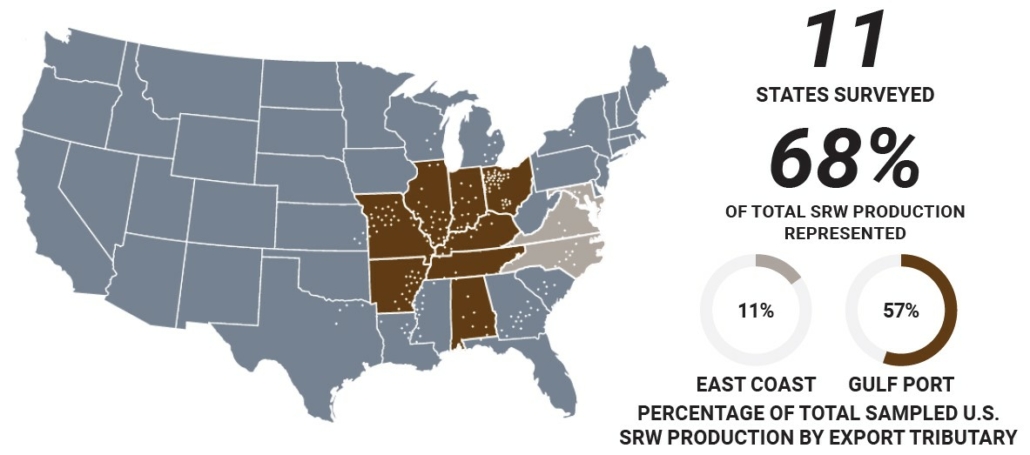

USW promotes the quality advantages of all six U.S. wheat classes. For snack foods, soft red winter (SRW) wheat and soft white (SW) wheat are most commonly used. But hard white (HW) wheat, hard red winter (HRW) wheat and hard red spring (HRS) wheat each are a quality ingredient – ether for snack foods and breads, or as part of flour blends to produce snack foods.

Wheat can also be used in other forms to make snack products. Flaked or puffed wheat is commonly used to manufacture breakfast cereals and cereal snack bars. Wheat bran is added to biscuits, cakes, muffins and breads to increase the dietary fiber content. Wheat germ can be added to breads, pastries and biscuits, or sprinkled onto yogurt, breakfast cereal or fruit dishes to increase the B-Vitamin, protein and fiber content.

USW also provides millers and bakers around the world technical support, including assistance in applying Solvent Retention Capacity (SRC) analysis to better predict performance characteristics of flour for cookies, crackers and cakes.

USW Bakery Consultant Roy Chung says consumers in Asia are more and more interested in “on the go” foods – crackers, cookies and even something as simple as a slice of bread with toppings.

A ‘Wheat Team’ Effort, Here and Abroad

“Snackification is definitely a thing in the Philippines, with bread being primarily used for snack foods,” said Joe Bippert, USW Associate Regional Director in South Asia. “All across the region, there are many, many products that have fallen into the snack category, some traditional like crackers and cookies, and some new. We are working with buyers, millers and bakers to make sure U.S. wheat is part of this snackification movement. We also continue to work with our partners to develop new products with U.S. wheat.”

One of those partners is the Wheat Marketing Center (WMC). Based in Portland, Oregon, the WMC regularly conducts research projects on snack food-related topics and wheat flour formulations. USW offices around the world connect snack food makers to the WMC, which works to develop new products to meet changing consumer demands for attributes such as lower sugar or salt, new flavors or even different shapes of crackers, cookies, cakes, breads and other snacks.

A Universal Phenomenon

No one seems to know who created the term “snackification,” but it began appearing in trade journals and food blogs a decade ago. As it did then, today it is used to describe a trend in which consumers snack in place of meals.

A Harris Poll survey commissioned by Mondelēz International last year polled consumers in 12 countries. It found that more than 55% of consumers “nibbled frequently throughout the day” in place of three standard meals, while 71% said they snacked at least twice each day.

Mondelēz International’s fourth annual “State of Snacking” report that “snacking increasingly replaces traditional meals in consumers’ lives.”

“Our State of Snacking report confirms that in these trying times, consumers around the world view their favorite snacks as affordable and necessary indulgences,” Dirk Van de Put, Chairman and CEO of Mondelēz International, noted in the report. “Snacking continues to be a way for consumers to connect or to enjoy a moment of delight in their day, further demonstrating our belief that every snack can be enjoyed in a mindful way.”

Looking back, it is clear urbanization drove snackification, Quash explained.

“Convenience and portability were key due to time pressures and a culture where people were constantly under constraints and were looking for foods to eat while on the go, foods they could eat on their way to the office or in the office while working,” he said. “Although people are still spending more time at home than they did pre-pandemic, snacking has become part of the routine.”

Crackers, Cookies, Biscuits . . . and Bread, Too

In some cases, foods just changed roles. One key consumer trend for U.S. wheat is the fact that breads that were once a big part of traditional sit-down meals are in some countries being used to anchor snack time.

Roy Chung, USW Bakery Consultant based in Singapore, said consumers in Asian countries are walking into retail stores looking for “simple and fast.” In many cases, how the foods are packaged is the biggest factor.

“When it comes to wheat, products range from simple slices of bread made into different types of sandwiches, or just plain bread spread with margarine and topped with sugar, then packaged to eat on the move,” Chung explained. “There are buns with different kinds of fillings, including steam-type buns. These are considered a snack that can fill you up without having to pause to prepare a meal. Grab it and go, as they say.”

Microwave-ready cakes and muffins, prepared in a paper cup and baked at the store, are common.

“In the cracker category, there is canned tuna or salmon or sardines packaged with a stack of crackers, which are popular for people taking a day trip or a bus ride somewhere and are eaten in place of lunch or even dinner,” said Chung. “All of these products are a showcase for the quality of U.S. wheat.”

Consumers shopping their local food store for snacks have other demands, too.

“The snacking trend remains based on convenience, but consumers around the world have become more focused on three things: mobility, value and health,” said Quash. “For the wheat industry, those are generally good things because wheat products tend to deliver on all three.”

By Ralph Loos, USW Director of Communications