On behalf of the U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) Transportation Working Group, we* appreciate the opportunity to provide comments on the draft Lower Snake River Dams Benefit Replacement Report.

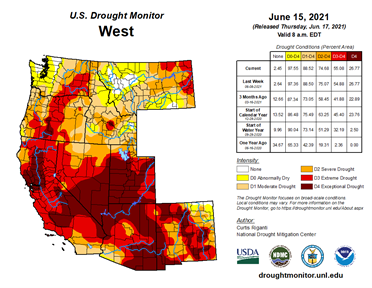

The draft report raises serious concerns among U.S. Wheat Associates (USW) and its member states. The USW Transportation Working Group (TWG) questions many of the baseline assumptions argued in the draft report. The draft is incomplete because many of the key variables cannot be quantified. The Lower Snake River Dams (LSRD) provide a critical need that moves U.S.-grown wheat to high-value markets around the world. Breaching the dams would have serious economic consequences for producers and grain handlers. Removing the dams also runs counter to achieving climate-friendly goals.

Barging Benefits

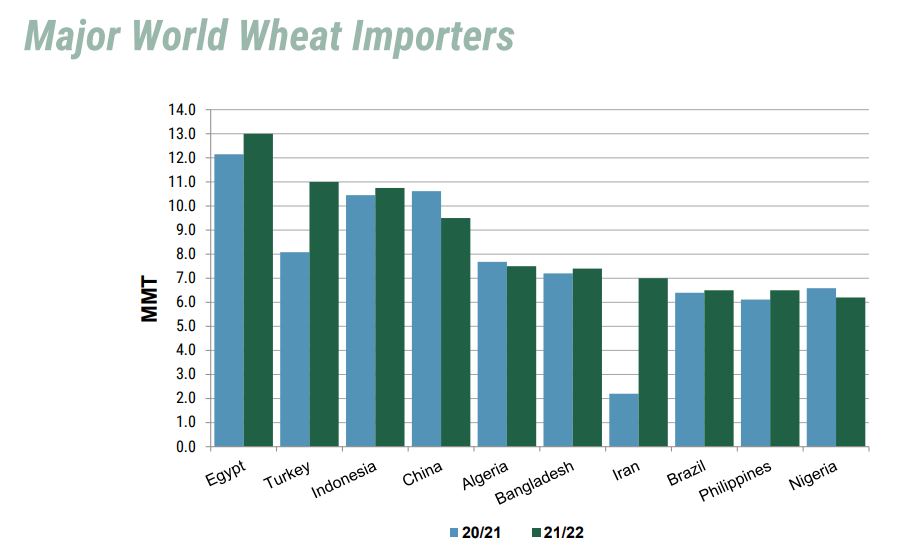

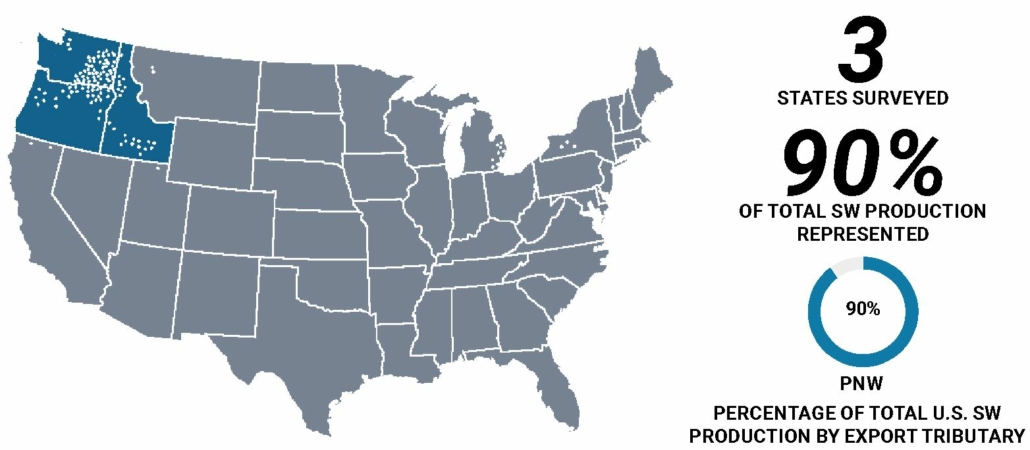

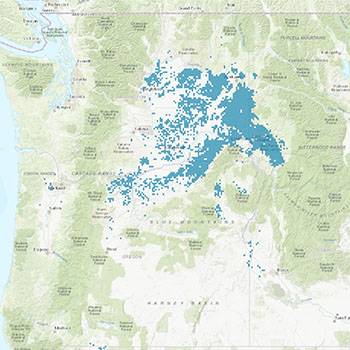

USW strongly supports the sustainability and reliability of wheat transportation by barge. The Columbia Snake River System is an essential part of a logistical web that moves over half of all U.S. wheat exports to more than 20 Pacific Rim countries and encompasses some of the largest U.S. wheat buyers in the world. The Snake River moves more than 10% of all wheat that is exported from the United States. Because of the cost savings conveyed by barging grain and examples used in the draft report, we can conclude that farmers save considerably by using the waterway in place of rail or truck and are able to pass on savings to consumers.

The Lower Snake River Dams provide critical needs for wheat farmers, grain handlers, merchandisers, and millers. The draft report clearly outlines the benefits enjoyed by grain handlers, “barging is the lowest-cost option (per ton-mile) for wheat shipping, an additional benefit for Pacific Northwest producers, as they operate on narrow cost margins and use barging to maximize their profit per bushel.” Shifting the current volume of wheat and other grains moving via barge on the LSRD over to rail or truck is not a viable and straightforward solution as portions of the draft study imply. Rail and truck cost significantly more on a per bushel basis, and trucks have distance limitations.

Breaching Increases Transportation Costs

An excerpt from the draft report outlines the literal costs to farmers: “One of the most significant transportation impacts connected with LSRD breaching is shipping costs. Several studies cite shipping prices during scheduled lock outages for maintenance between December 2010 and March 2011 and found that during the outage, over 90% of the grain by volume was shipped by rail and that shippers experienced a nearly 40% increase in shipping and storage costs.” This example shows that railroads will use their power to raise rates when other alternatives, like the river system, are unavailable.

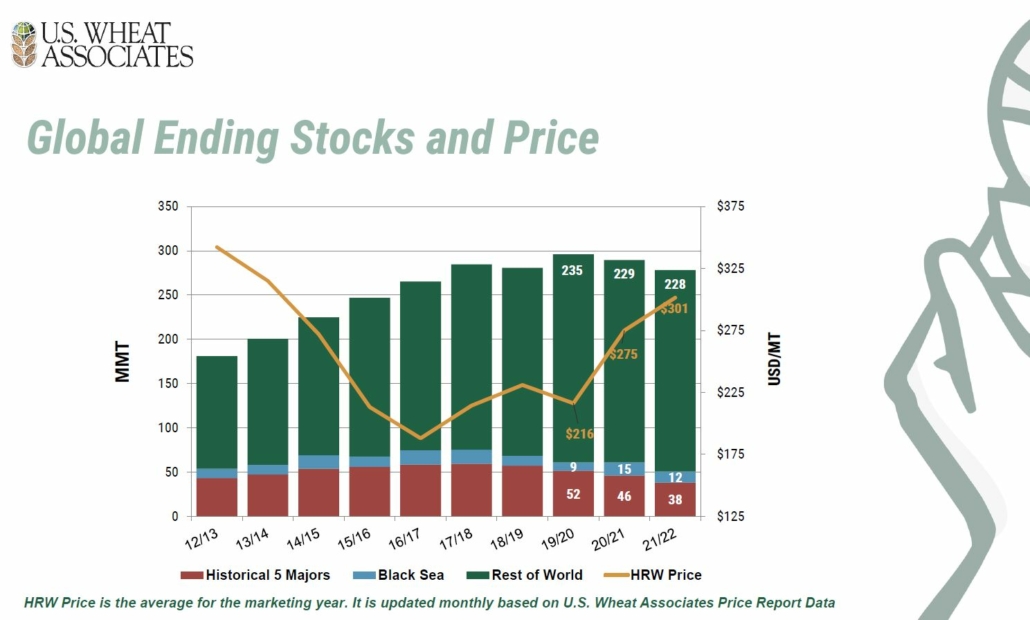

The Port of Lewiston is the most inland port in the U.S, Pacific Northwest. Its placement on the Snake River allows farmers in Idaho and other states to barge their wheat efficiently and affordably. The U.S. competes with six other primary wheat-exporting countries. According to the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), the United States is the third-largest wheat exporter in the world. However, for the U.S. to remain competitive with other wheat exporting nations, export prices must remain competitive. Inland transportation costs are a primary factor in determining the competitiveness of U.S. wheat. Using barges to ship grain is one of the most efficient and cost-effective ways that U.S. wheat farmers stay competitive.

Rail Cannot Make Up Difference

All wheat production zones in the U.S. would be impacted, not just those in close proximity to the Lower Snake River Dams system. The U.S. rail system has some severe issues with service and reliability, and in recent years, tariff costs to move wheat have steadily increased. Adding more volume to the system would raise costs for all farmers and lead to a decline in service for a significant portion of all U.S. wheat producers. This would directly impact U.S. wheat’s global competitiveness as an export market.

Transporting wheat by barge is an environmentally friendly alternative to rail and truck hauling. One four-barge tow can move as much grain as 144 rail cars or 538 semi-trucks. Removing the dams would not only remove clean hydroelectricity but would mandate more significant carbon emissions as grain handlers are forced to rely on railroads and semi-trucks for long-haul delivery to export facilities in Portland and elsewhere.

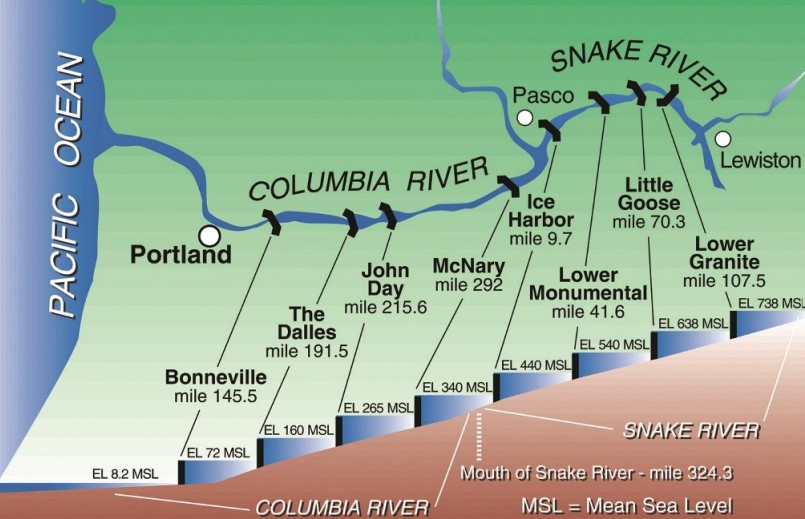

Eight Steps Down. Lock and dam systems on the Columbia Snake River System allow barges to efficiently and safely navigate the 222-meter elevation change from Lewiston, Idaho, to export elevators as far west as Longview, Wash.

More Competition Not Less

The draft report provides no sincere considerations for alternative freight, and what suggestions it does make are unrealistic. While railroads and trucks compete with barge companies to move grain, farmers and grain handlers would be held captive without barges as an alternative.

USW supports the Columbia Snake River System and will continue to emphasize its importance in serving wheat buyers worldwide. Breaching of the dams on the Lower Snake River would have a devastating economic impact on wheat production and market competitiveness, not just in the Pacific Northwest Region, but nationally.

*This article represents public comments by the USW Transportation Working Group to the Lower Snake River Dams Benefit Replacement Report submitted July 11, 2022, by working group co-chairs Jim Peterson, Policy and Marketing Director, North Dakota Wheat Commission, and Charlie Vogel, Executive Director, Minnesota Wheat Research & Promotion Council.