By Stephanie Bryant-Erdmann, USW Market Analyst

The common refrain right now is “the world is awash with wheat.” While that is true in the aggregate, in terms of milling wheat and, more specifically, high-protein milling wheat, supply is very tight. The impact of the small supply of high-protein milling wheat can be seen in the protein premiums for both U.S. hard red spring (HRS) and hard red winter (HRW) wheat. The following is a breakdown of pricing and availability of the U.S. high-protein wheat supply by class and port of export. Please note that U.S. wheat protein is expressed on a 12 percent moisture basis, not on a dry matter basis, thus U.S. 11.5 percent protein is equal to 13.1 percent protein on a dry matter basis.

Hard Red Winter

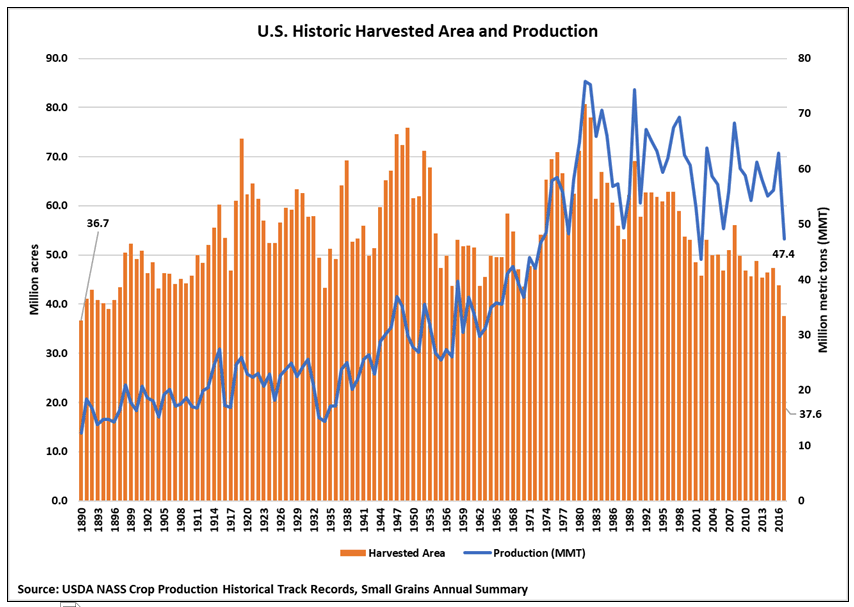

According to USDA, HRW production fell 32 percent from 2016/17 to 20.4 million metric tons (MMT), putting total HRW supply at 36.5 MMT. According to USW Crop Quality data, the average protein of this year’s HRW crop is 11.4 percent. That is similar to last year, but below the 5-year average. Overall, 55 percent of HRW samples were less than 11.5 percent protein; 26 percent had 11.5 to 12.5 percent protein and 19 percent had protein levels above 12.5 percent. Extrapolating that to HRW production, there is roughly:

- 9 MMT of HRW with protein greater than 12.5 percent;

- 3 MMT with protein between 11.5 and 12.5 percent; and

- 2 MMT with less than 11.5 percent protein available.

The smaller crop and lower protein support both the Kansas City Board of Trade HRW futures market and protein premiums; however, that support varies by export tributary.

Gulf. The 2017/18 marketing year (beginning June 1) average protein premium for Gulf HRW 12.0 percent protein on a 12 percent moisture basis (mb) is 51 percent above the 2016/17 marketing average at $69 per metric ton (MT) and $20 dollars per MT above the 5-year average. The HRW Gulf export tributary region experienced its second consecutive year of higher yields and very limited heat stress during the growing season, resulting in lower than normal protein. According to USW Crop Quality data, the average protein for Gulf export tributary HRW is 11.2 percent, compared to the 5-year average of 12.8 percent protein. This means that while protein premiums for high-protein HRW are climbing, ordinary HRW from the Gulf represents a significant bargain for customers with export basis levels 31 percent below the 5-year average at $28/MT.

Pacific Northwest (PNW). Unlike the Gulf export tributary states, HRW in the PNW tributary states was stressed by high temperatures and little rainfall in 2017/18, boosting protein content but cutting yields. According to USW Crop Quality data, the average protein for PNW export tributary HRW is 12.0 percent, similar to the five-year average but higher than the average of 11.7 percent protein in 2016/17. USDA estimates the PNW HRW tributary states sampled by USW produced 3.5 MMT, or just 17 percent of the total U.S. HRW supply. With the PNW supply limited, albeit a supply with higher protein than the Gulf, the average price for 12.0 percent protein HRW is 9 percent higher than the 2016/17 value at $238/MT, but still well below the 5-year average of $277/MT. This represents an excellent opportunity for customers to lock in prices before supplies dwindle in the second half of the marketing year.

Hard Red Spring

According to USDA, HRS production fell 22 percent to 10.5 MMT in 2017/18. Total HRS supply declined 18 percent from 2016/17 to 20.8 MMT on smaller production and beginning stocks. According to USW Crop Quality data, the average protein of this year’s HRS crop is 14.6 percent. That is above both last year and the 5-year average of 14.0 percent. Overall, 22 percent of HRS samples tested had less than 13.5 percent protein; 23 percent of samples had 13.5 to 14.5 percent protein and 55 percent of samples had greater than 14.5 percent protein. If that is extrapolated out to HRS production, then roughly:

- 8 MMT of HRS was produced with protein greater than 14.5 percent;

- 4 MMT having protein between 13.5 and 14.5 percent; and

- 3 MMT with less than 11.5 percent protein available.

This distribution caused protein premiums for HRS to fall below the 5-year average, but supported HRS MGEX futures, which spiked in July and remain an average $49/MT above last year’s futures prices due to the smaller supply. Like HRW, price impacts of the smaller supply vary by export tributary region but were more evenly distributed due to a nearly even production split between regions.

Eastern Region. The average cash price for Gulf HRS 14.0 percent protein is 16 percent above the 2016/17 marketing average at $298/MT. The higher price is supported by the extreme drought across the U.S. Northern Plains which cut production but boosted protein content. USW Crop Quality data showed the average protein for Gulf export tributary HRS was 14.4 percent, compared to the 5-year average of 14.0 percent protein.

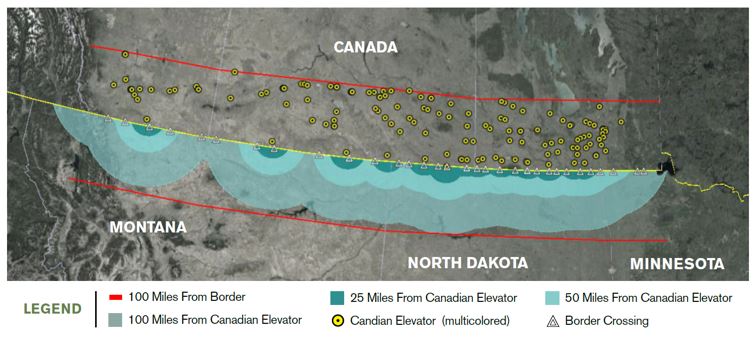

Western Region. The drought had devastating effects on yields in the Western Region, specifically in Montana and western North Dakota and South Dakota, but did boost protein levels. According to USW Crop Quality data, the average protein for the PNW export tributary is 14.9 percent, compared to the 5-year average of 14.2 percent protein. With the increased availability of high-protein HRS, the average protein premium for 14.0 protein HRS fell 10 percent year over year to $53/MT, well below the 5-year average of $67/MT.

With Canadian wheat production falling an estimated 5.5 MMT year over year and the sharp drop in U.S. high-protein wheat production, the global supply of high-protein wheat has tightened. Depending on what protein specifications customers need, this may be the best time to lock in lower HRS protein premiums. Low-protein HRW also represents an excellent buying opportunity for specific customers.